With the immediate roadblocks removed the way was open for an election that would be the final step in the formation of a democratically elected government.

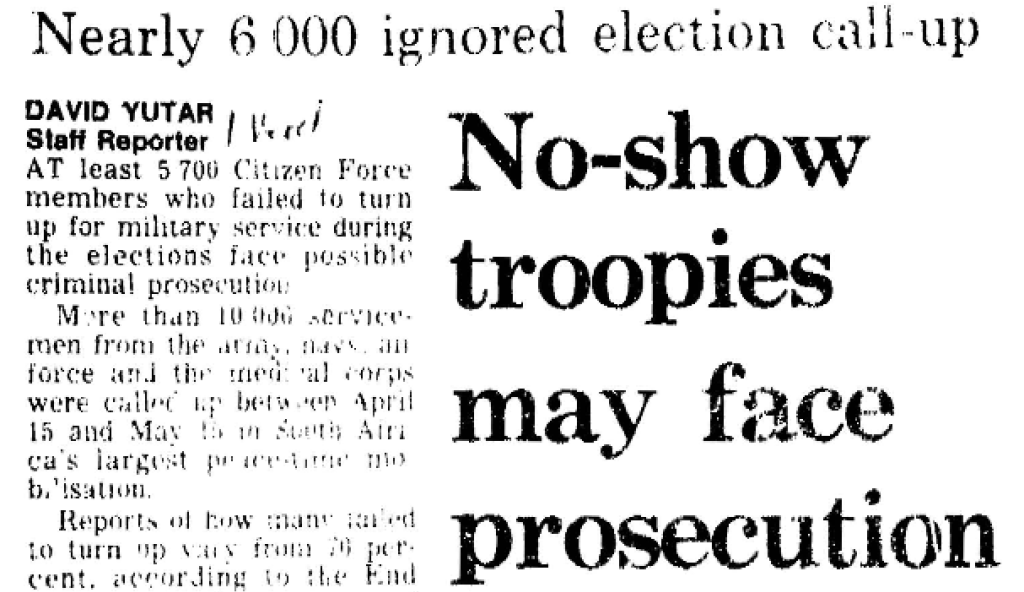

The key elements for a successful election were in place. The Transitional Executive Council had been established in October 1993 to promote the conditions for free political activity in the run-up to the elections.22 The commitment of the security forces saw the biggest ever peace-time mobilisation between 15 April and 15 May to secure the election. The main political parties had strong party campaign machineries. Even the Inkatha Freedom Party which had only agreed at the last minute to participate turned out to be well-prepared for a campaign. Voter education amongst the majority who had been denied the franchise had begun almost two years before the election date had been agreed, when the ANC started preparing for the elected constituent assembly it wanted. The Independent Electoral Commission, established in December 1993, was in place.

On the other hand it was an election with many challenges which led to difficulties both in its conduct and in the counting of votes. The IEC had only four months to prepare for an election in which most of the expected twenty million voters had never voted; without a voters roll; with little or no electoral infrastructure in much of the country; and with some reckless organisations still bent on sabotaging the election or undermining its legitimacy When the IEC was established, Mandela telephoned its newly-appointed head, Judge Johann Kriegler, to say that he and the ANC realised that there were difficulties, and that Kriegler should know that he had the support of the party and its confidence.23

For Mandela, beyond being the leader and face of the ANC campaign, the fundamental issue was to ensure the legitimacy of the founding election, as an essential condition for a peaceful transition to democracy.

My first contact with Mandela was a phone call fairly early on encouraging me in the work of administering the election

The formation of the first democratically elected government of South Africa was preceded by a countrywide election campaign during which ANC leaders in all levels of the organisation systematically combed the entire country, visited rural and urban areas and spoke to all sections of the population.

It is this team of men and women that made 27 April 1994 unforgettable in the collective memory of the South African nation as a day in which our people came together and united in symbolic action.

That day concluded months of excitement, expectations and fears following the conclusion of negotiations in November of the previous year.

The election date was agreed at the negotiations so that for five months the nation waited with bated breath for the arrival of that historic day in the life of South Africa.

To the black majority, it meant the birth of a dream that had inspired generations, namely, that one day the people will govern.

For decades, after the conclusion of the colonial wars of dispossession, they had to sit on the side-lines of political life watching their compatriots voting to rule over them. Now the day was nearing when they would, together with all their compatriots, decide on the politics of their country.

To many of the white population, the prospect of that day obviously held cause for trepidation, fear and insecurity. To them it would signal the end of minority control and privilege, opening up the frightening prospect of having to share with those whom they subjected for so long and in many respects so cruelly.

The atmosphere in those months leading up to the election day was therefore understandably a mixture of all of those different and competing emotions and expectations. As we went around the country campaigning and canvassing our people to come out to vote for the liberation movement, we encountered those various moods.

It was clear that the hard work done by the liberation movement over so many decades had left an indelible mark on the voting patterns to be expected. All over the country and in all communities, we were greeted with enthusiasm and overwhelming signs of support.

The ANC President travelled to virtually every corner of the country. In the run up to the elections during the last six months, he personally addressed at least two and a half million people through rallies and meetings across the length and breadth of South Africa. It was moving to observe how the name and reputation of our movement lived in even the remotest rural areas.

In the long established tradition of our organisation and of Congress Alliance politics we drew into our campaign the widest possible array of people. As we had done during negotiations when we managed to win over to our side different parties who originally were thought to be allies of the apartheid regime, we now again adopted that broad approach to unite people even in campaigning.

We used modern research techniques and methodologies including opinion polling. Our polling adviser was Stan Greenberg who was adviser to Clinton in his 1992 campaign.

In the campaign we held People’s Forums, focus groups and inserted media adverts seeking inputs from the people. These yielded enormous responses. We engaged with the people face-to-face.

We also engaged the masses in an active voter education campaign. The President organised some skilful personalities to help in this regard. One of them was Leepile Taunyana, then President of the National Professional Teacher’s Organisation of South Africa. He replied that the President was late, he and his colleagues in NAPTOSA had already started the voter education campaign.

We were tremendously inspired because he led a strong and disciplined movement, which had enough resources to wage a powerful campaign. We had made the same appeal to the South African Democratic Teachers Union, who had already taken the initiative also before we appealed to them to join.

The ANC sought not to speak to the people, but to speak with the people.

I conducted the campaign as member and President of the ANC, having been elected to the latter position by the first national conference of the organisation, after it was unbanned, which was held in Durban in 1991. We conducted mock elections as part of the voter education campaign. Ten million people took part . This was very important, as in the actual elections there were only less than ten percent spoilt papers . This spoilt paper percentage is in line with the performance in elections in democracies with developed economies with a high level of literacy.

The ANC conducted a positive campaign, focussed on rebuilding, reconstruction, and a better life for all without forgetting the past. We avoided negative campaigning, avoided attacking opposition parties. To the best of my memory, we never placed a single negative advert in the media. The opposition, on the other hand, were primarily negative, and kept attacking the ANC and its alliance partners.

As always, we were mindful of the minorities in our questions about the future at such times of great transition. Our movement had always been one concerned for all of the people of our country and we sent that message to the country during our campaign. People responded with enthusiasm.

We remember, for example, how a young woman from the Coloured community, Amy Kleinhans, the then reigning Miss South Africa, joined us on stage during our campaign in Cape Town. She had earlier angered the then State President, FW De Klerk, because of her refusal to carry the national flag of apartheid during an international beauty pageant, confirming her allegiance to the new South Africa about to be born.

There were other such demonstrations of enthusiastic support. One young teacher from the community left his post to sing songs composed by himself for the campaign. This young man, John Pretorius, later recorded the song ‘Sekunjalo’ which he sang at so many rallies in the Cape during the election campaign.

On voting day, an elderly African lady from the Northern Transvaal, as it was then known, told the election official at the polling station that she wanted to vote for the boy who came from jail. Although she mentioned some name, she did not know to which organisation he belonged. After interrogation, the polling station was able to sort out the problem to her satisfaction.

As we have mentioned, though, everything was not of that positive and joyous scale. In KwaZulu-Natal, we had to cope with the continuing political violence that cast a spell of gloom and doubt over the otherwise exciting prospects of democracy. We concentrated a lot of our time on the political situation in that province. On the one hand, we had to campaign for the election victory of our own organisation, while at the same time it was our duty to address in a non-partisan way the fate of all of the people in the province. The political violence, no matter by whom it was being committed, was to the great damage of all South Africans. And as always in such circumstances, the innocent carried the brunt of suffering, hence our special attention to the then province of Natal.

Our election campaign did not always proceed smoothly. As pointed out above, the National Party of De Klerk was extremely negative, and at times, plainly immoral in its campaign.

When I visited Los Angeles in the early nineties, I took a photograph flanked by two internationally famous artists, Elizabeth Taylor and Michael Jackson. In the run-up to the April 1994 election, the National Party published a scurrilous pamphlet entitled ‘Winds of Change’ in which they cut out Michael Jackson; and Elizabeth Taylor and I now appeared all alone. They aggravated that deceitful exercise by making defamatory remarks against both of us. The Independent Election Commission forced them to withdraw the pamphlet.

The National Party campaign was not only immoral, but also racist. They exploited the fears of the racial minorities, especially those of the Coloured and Indian communities, by arguing that a victory of the ANC would result in their oppression by Africans. They criticised Dr Alan Boesak, a prominent cleric from the Coloured community, for campaigning for all sections of the South African population, instead of confining himself exclusively to Coloureds.

Another example of this racism was again directed against me personally. Heidi Dennis, a young Coloured teacher from the Beacon Valley Senior Secondary School in the Coloured community of Mitchell’s Plain, asked me to help them to raise funds to paint their school. I then requested Syd Muller of Woolworths, not only to provide funds as asked by Heidi, but to upgrade the school by building more classrooms and a laboratory.

When Woolworths completed this project, we went to launch it. A large group of Coloured women staged a protest demonstration against me. One of them screamed and said in Afrikaans, ‘Kaffir gaan huis toe.’ (Kaffir go home), a derogatory jibe. All these racist and deceitful manoeuvres were committed by De Klerk’s party, a leader I had repeatedly praised inside and outside the country as a man of integrity with whom we could do business.

The ANC tried to the best of its ability to avoid descending to the level of the National Party. We remained focussed and constructive. We strongly urged all South Africans, irrespective of colour or creed, to join the fight for a democratic, united, non-racial and non-sexist South Africa.

In that campaign, we also experienced difficulties from some of our members who made rash statements contrary to our basic policy. We immediately condemned publicly such behaviour.

The correctness of that strategy was fully rewarded when we won a landslide victory at the polls.

The white right-wing was another potentially destabilising factor that affected the general mood during the period leading up to the elections. How we managed to neutralise that threat and bind the leadership into constructive participation is told in more detail elsewhere in this book.

Stories were abounding about whites who were adopting a siege mentality, stocking up their houses with food and other emergency supplies. After the elections, when all was over and matters turned out so differently to what the prophets of doom had predicted, there was great mirth and levity about those who stockpiled in such fashion. But at the time, it was a matter of great seriousness and it did affect the overall mood.

On the organisational and logistic level just as much public interest was generated. The Independent Electoral Commission set about preparing for the elections, establishing offices in different parts of the country. Amongst their tasks was to monitor the general atmosphere that could affect the measure to which the elections would be free and fair.

It filled one with pride to observe how many South Africans were warming to the mechanics of democratic elections. It was said by some commentators that the system of voting for that day would be too complex and complicated for the supposedly unsophisticated voters. We had decided on a system of proportional representation; voters had to vote for the national legislature and the provincial one on same day. All of these were thought to hold complexities that might be confusing to voters.

In the end, it turned out that South African voters had an almost natural affinity to the process of voting.

There were scores of foreign observers who also travelled the country, including my future wife, Graca Machel, either assisting in voter education or monitoring the situation during the campaign period, ensuring that the conditions for free and fair elections existed. Almost without exception, they afterwards commented about the positive spirit that existed in the country.

There were other mechanisms operating to assist South Africans to operate in the spirit of open democracy in the run-up to the election. Amongst these was the Independent Media Commission to ensure that all parties were fairly treated by the media, both in reporting and coverage.

When the 27th of April eventually dawned the South Africans queued in their millions to cast a democratic vote, the foundations had been laid during those preceding months. That memorable day fittingly capped the positive spirit of hope and expectation that reigned predominant in spite of the fears and trepidations.

The smooth and orderly manner in which the elections occurred, and the violence-free transformation that followed, completely shattered the depressing predictions of the prophets of doom, who included some of the well-known and respected political analysts. They had predicted that the history of South Africa, especially during the four decades of the apartheid regime, clearly showed that the white minority was determined to cling to power for centuries to come. A wide variety of commentators underestimated our determination and capacity successfully to persuade opinion makers on both sides of the colour line to realise that this country is their beloved fatherland, with primary responsibility to turn April 1994 into a memorable landmark in our turbulent history.

As the pivotal moment in the transition to democratic government, the election was a success. Big problems arose and were overcome by measures that included agreement across the board to extend voting by a day. The difficulties related to the late participation of the IFP; the distribution of ballot papers and other supplies to voting stations especially in rural areas; violence and problems of free political activity in KwaZulu-Natal; and long queues. Last-minute attempts to stop the election had been foiled. A hacking of the vote counting system to inflate the votes for the National Party, Freedom Front and Inkatha Freedom Party had been detected and dealt with by the elections commission.25 Popular participation had been high and enthusiastic.

The declaration of the legitimacy of the election, as ‘substantially free and fair’, was uncontested. But this had not been achieved without intervention by party leaders deflecting calls from within their parties to mount challenges.

During the counting a delegation of ANC provincial leaders from Natal went to the ANC national headquarters with evidence of irregularities that favoured the IFP. Over their protestations and demands that the ANC challenge the results in the province, Mandela insisted on accepting the ANC’s narrow loss of the province rather than mount a challenge which could cost the legitimacy of the election and have serious implications for political stability and peace. It also decided to accept the overall outcome that issued from the IEC, in spite of suggestions, from various quarters, to negotiate a deal that would have compromised the integrity of the process.

Some National Party leaders similarly approached De Klerk, demanding a legal challenge of the results, alleging irregularities favouring other parties. De Klerk took the view, he says in his memoirs, that ‘despite all the irregularities we had little choice but to accept the outcome of the election in the interest of South Africa and all its people.’26 The Democratic Party in Gauteng also considered a challenge, but didn’t follow through.

While the election provided a legitimate bridge of transition, as a measure of a united nation in the making, aspects of the election troubled Mandela and preoccupied him in the coming years.

Seen from a geographical perspective, two provinces were not won by the ANC – KwaZulu-Natal and Western Cape- and a third province, the Northern Cape, was won by the ANC with under fifty per cent.

Measured by the vision of a united and non-racial nation, the results reflected continuing attachments to old divisions. In provinces other than KwaZulu-Natal, leaders and supporters of regional political formations based on the bantustan structures and traditional relations mainly aligned themselves with the ANC. In KwaZulu-Natal, however, the Inkatha Freedom Party retained the allegiance of a sizeable body with a strong regional and ethnic slant.

Voting in the segregated Indian and Coloured residential areas pointed to greater support for the National Party than for the ANC in particular, especially – though not only - among working class voters, reflecting a sense of threat to their position from the likely advance of African workers. For Mandela this signified not merely a set-back for the ANC in narrow electoral terms, but a serious challenge for the building of a non-racial nation.27

Both of these matters, the regional, traditionalist stance in Kwazulu-Natal and concerns of the working-class and others in Coloured and Indian communities, were to be a strong focus for Mandela’s leadership of the transition in the coming years. But they were issues for the future, barely touched on while celebrating a successful and decisive election.

we have outlined in our discussion documents initial assessment of the election results and their implications