Preparation for the inauguration had begun months before the election, when the Transitional Executive Council established a National Inauguration Committee (NIC) to see to the political and protocol aspects of the inauguration, the logistics of which were being handled by the government and security forces.

It was chaired by Chief Justice Corbett – who later presided over Parliament’s election of Mandela as president, administered the oath of office at his inauguration and officiated at the swearing in of cabinet ministers. The committee included leading representatives of civil society. Its steering committee was co-chaired by the Director-General of Foreign Affairs, Rusty Evans, and the Deputy Head of the ANCs Department of International Affairs, Aziz Pahad.

The combination of a judicial chair, a steering committee whose primary domain was international relations, and the involvement of civil society reflected both the scale and historical significance of the event that was being prepared for. Previous inaugurations had been relatively low-key and, given apartheid South Africa’s international isolation, had negligible foreign attendance. The NIC’s founding document echoed the interim constitution, declaring that ‘the NIC shall reflect the spirit of national reconciliation and unity.’36

The government’s initial proposal to the NIC was for an inauguration in Cape Town at the Good Hope Centre, a confined venue,37 but the political parties insisted that it had to be at the seat of political power, the Union Buildings in Pretoria, with invited guests in the amphitheatre and the public on the lawns, all witnesses to the swearing in of the President.38 It was to be not only the induction of South Africa’s first democratically elected President, but the sealing of the international community‘s acceptance of a democratic South Africa.

Mandela himself paid attention to who would be there, both from other countries and South Africans.

In the first week after the count had come out, we were then preparing for the inauguration. What touched me was Madiba looking with Thabo and Aziz at the list of international guests.

There were people that he insisted had to be invited, must be invited: ‘I’m not going to have this without Castro.’ He always went back to those people, those were friends. And he had to have Yasser Arafat at his inauguration. He said, ‘I don’t care how we do it, my brother Yasser Arafat must be at my inauguration.’ That was a big challenge because the poor man couldn’t leave Tunisia, he was going to be arrested.

He had a view that every African leader who could possibly come should be invited. He said, ‘We need to be part of what Africa is going to look like and shape it and build it.’ If he was told someone could not come, he wanted to know. And then he’d pick up the phone – ‘Oh my brother, I believe you can’t make it but you know I would really like you to be here.’ And people couldn’t say ‘No’ and they did come.39

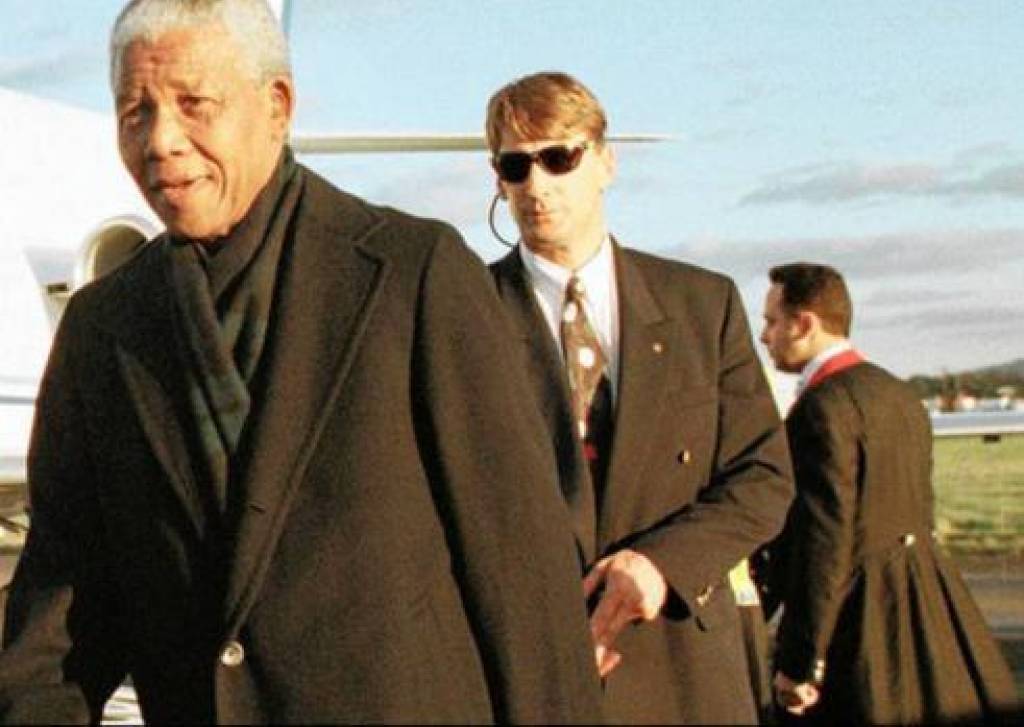

On the day the number of heads of state and government arriving for the inauguration was so far beyond any previous experience that things soon fell behind schedule. When Chris Streeter, the official assigned to Mandela for the occasion went to the presidential guest house to tell him of the delay, he found him in his room ‘lying on his bed with his dark suit and his red tie and his feet that much off the end of the bed, taking a break.’ On hearing that the programme would start an hour late, he responded, ‘Not a problem. ... Would you mind going to tell Mr De Klerk that he must take it easy and relax. It’s going to start only at 11 o’clock.’40

The ceremony was rich in symbolism and emotion as heads of state from more than 160 countries sat in the amphitheatre of the Union Buildings. It was ceremonially recognized by the police and military forces whose historic mission had been to prevent what was happening but who were now securing the conditions for a peaceful transition. Fighter planes and generals saluted the president and pledged allegiance. In the moment between the singing of Die Stem, the anthem of the old, oppressive, South Africa and the singing of Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika, the anthem of liberation, the new South African flag unfurled.

Asked years later what he was thinking as he took the oath, Mandela said it was difficult to remember, except that:

He was lying on his bed with his dark suit and his red tie and his feet that much off the end of the bed, taking a break

I knew now that I was being inaugurated as the first black president of South Africa and I was aware of the impossible task before me. I had to go forward to add to what our people did in the battlefield as well as what De Klerk did in announcing publicly that the time of apartheid is past.41

Mandela’s speech – the product of collective effort with Thabo Mbeki at the head - matched the symbolism and spoke to South Africa and the world. Celebrating ‘newborn liberty’, Mandela invited all of South Africa and the international community to bask in ‘a glorious human achievement’ that was ‘a common victory for justice, for peace and for human dignity’. He affirmed a common humanity and allegiance to South Africa. He lauded the achievement as collective effort of many sectors of society, singling out FW De Klerk for his role. He paid tribute to the security forces for securing the first democratic election and the transition to democracy. And he pledged a new future, in which ‘we must act together’ for reconciliation, nation-building and social emancipation, a future which would never again see ‘the oppression of one by another’.42

Then Mandela took the founding message to different audiences throughout the day.

From the formality of the amphitheatre he moved to the lawns of the Union Buildings where tens of thousands of people were gathered. On the stage he introduced Thabo Mbeki and De Klerk as the deputy presidents, lifting their hands to the air in his, in a gesture which De Klerk recalled years later: ‘I will always remember him holding up my hand, and also the hand of Thabo Mbeki, for all to see. It was symbolic of us approaching the future together.’43 He described Mbeki as a freedom fighter who had sacrificed his youth to work for liberation and De Klerk as one of the greatest reformers, one of the sons of the soil. ‘We have forgotten our differences’, he said, ‘and are now healing the wounds of the past – it is for you to help us.’44

Then, at the inaugural luncheon of invited guests he spoke in a different idiom, ‘from the heart’ as he was wont to say when he spoke without text or notes.

Many forces have influenced the history of our country, as they have done in the history of other countries. But for one or two moments I want to talk about two forces which have been of particular relevance in the history of our country.

... We are aware of the type of government we have had since 1910, which relied on brute force and coercion. ...But there has been another force: that of compassion, that of love and loyalty to your country, that of ignoring what is negative in a human being and concentrating on that which is good. Through dialogue, through persuasion, we have been able to bring South Africa out of that era of darkness, bitterness, pessimism, to a moment where the entire world has joined us to come and celebrate.

That is a lesson, not just for this day; it is a lesson on which we can build for the future.

He referred to ‘the strong friendships built between black prisoners and white warders,’ three of whom he had asked the NIC to invite to the inauguration, to share in the joys of the day ‘because, in a way, they also contributed to it.’

Then, of course, there’s my friend, Mr De Klerk. He was one of those who gave us a hard time. ... I mention this as a measure of the change he has undergone, the personal courage, the vision, the honesty, the integrity with which he came to examine the situation in South Africa, and used his enormous power as the head of the government to bring about reforms.

So, we have forgotten the past. We must know the past, so that, when we work together now in a Government of National Unity, we must know precisely what we have come through, what we should avoid. We said a lot of unkind things about one another during the election, but we have fought the election, we’ve had a good fight; now it is the time for us to put together the broken pieces of our country and to ensure that our people speak with one voice.

Today is the result of that other force in our country, that of persuasion, that of discussion, that of dialogue, that of love and loyalty to our common fatherland.

From the Union Buildings a helicopter took him to the Ellis Park stadium where South Africa’s soccer team was playing Zambia. There he again called for the nation to work together for change. What happened then, after a brief talk to the South African team during half-time, gave birth to the belief in the ‘Madiba Magic’. He had arrived at the end of a goal-less first half – but in the first minutes of the second half South Africa scored wo goals in quick succession and went on to win the match two goals to one.47