Years later, while working on this account of his Presidential years, Mandela reviewed the impact of the inauguration on South Africa’s media, and declared his satisfaction that the media had demonstrated ‘on this occasion and others their capacity to rise to the occasion.’ Newspapers and broadcasters shared in a national welling of emotions at the birth of a new era rich in promise of a better life for everyone.

Business, the media reported, was ‘full of confidence for a ‘Mandela boom’, with ‘business chiefs and leading economists oozing confidence over the country's economic prospects under an ANC-led Government of National Unity', predicting five to ten percent growth in the coming year as private investment converged with public sector investment in social infrastructure and low-cost housing.48

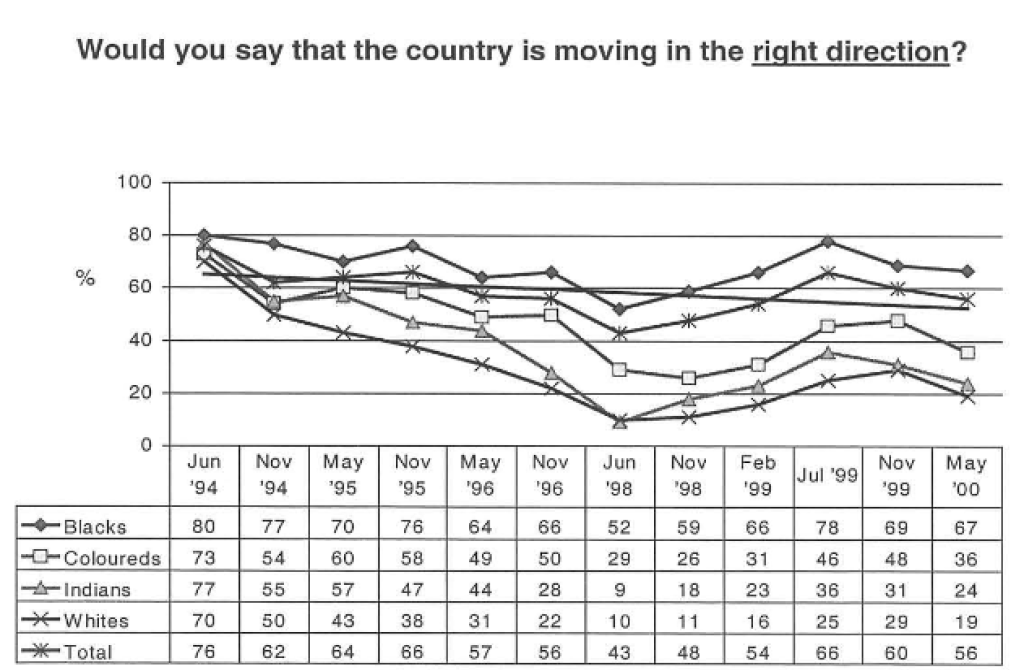

A national opinion-poll conducted shortly after the inauguration showed public mood at a euphoric and historic high – 76 per cent of those surveyed thought the country was going in the right direction and the gap between white and black opinion was the narrowest it would ever be.49

The morning after, the country was still reveling in the omens of a united nation liberated from its divided past, embraced by the world and made up of formations sincere in a commitment to work together to bring to fruition the aspirations whose achievements had now become possible, and which they saw embodied in their newly inaugurated president.

But there was ambiguity in the heightened emotions of the day. Was the new beginning one in which the slate of the past was wiped clean? Or was it rather the possibility of transforming and overcoming the legacy of that divided and oppressive past? This ambiguity would play out in the years to come, often antagonistically.

The democracy whose birth was being celebrated had not removed the social and economic consequences of the system whose political defeat was being celebrated – it had only brought the possibility of confronting them.

Eradicating or even reducing the legacy of poverty, unemployment and crime would have to reckon with an economy in crisis. Although the security forces had assured the election, half of those called up did not report for duty.50 Although the police and the IEC had foiled attempts to sabotage the election, the sentiments that motivated then attempts were still there. The election results traced the social fault lines of the past and measured the great distance to be travelled before a common sense of nation developed. The change in the country’s political system had come without a corresponding change in its economic system.