The military intelligence department which had incubated the report that led to Meiring’s resignation was just one of the apartheid intelligence agencies. The new government dealt with restructuring of the agencies early on, but even before that happened Mandela wanted a comprehensive overview of the security situation, and to that end had a series of meetings with the leadership of the national intelligence service, defence force and police. He told them what he wanted from the national intelligence service (yet to undergo restructuring).

The President and two Deputy-Presidents, the Ministers of Defence and of Safety and Security, Generals Georg Meiring and Van der Merwe should be briefed by the National Intelligence Service at the earliest possible convenience on the following issues.

1. Were any documents containing intelligence material destroyed or [possibly ‘edited’] and intelligence information wiped off from computers during the period 1 February 1990 and 31 May 1994?

a. If so, the reason for such destruction what was the material or inform : give full particulars of such material or information

b. The dates of such destruction or wiping off

c. The name or names of the persons who authorised such destruction or wiping off.

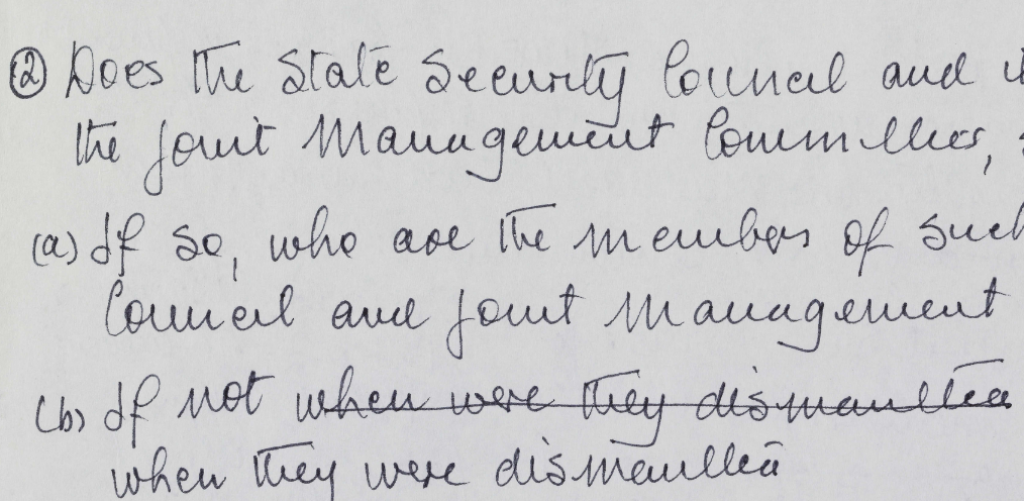

2. Does the State Security Council and its structures, like the Joint Management Committee, still exist?

a. If so, who are the members of such State Security Council and Joint Management Committees?

b. If not, the exact details of when they were dismantled

c. A list of members before they were dismantled

d. The purpose of the State Security Council

e. What happened to its funds and equipment

3. A list of the organisations on which NIS spied and a list of the agents of NIS who penetrated the organisations or institutions spied upon.

4. Does the Civilian Cooperation Bureau still exist? A detailed explanation of its structure and personnel must be furnished.

a. If not, when was it dismantled? What happened to its funds and other equipment?

5. Does the Directorate of Covert Collection still exist?

a. If so, who are its members?

b. If not, when was it dissolved?

c. What happened to its funds and equipment?

6. The original copy of the Report of General Pierre Steyn must be supplied.

a. Precisely for what criminal acts were several senior officers of the army dismissed or asked to resign as a result of that report?

7. Who is responsible for politically motivated violence which has led to the murder of close to 20,000 people?

8. It is alleged that the parties responsible for politically motivated violence were also responsible for the death of freedom fighters like Neil Aggett, Rick Turner, Imam Haroon, Ahmed Timol, David Webster, [Matthew] Goniwe and others, Griffiths and Victoria Mxenge; Pebco Three; Bheki Mlangeni

9. Did the Vlakplaas Unit continue to exist after 1/2?

Who were its members and what has happened to them.

What was or is its purpose before, or if it continued, what did its members do after 1990?

If dismantled, what happened to its funds and equipment?

The report by General Pierre Steyn in 1992 which Mandela referred to had done much to expose the hit-squads. Mandela had been briefed on some of its findings but had not seen the full report. It was on his desk shortly after this meeting.

The scope of Mandela’s list points to how deeply the intelligence services were involved in suppressing resistance. It explains his abiding caution and even mistrust at times, and why resignations from these structures put him on the alert.

The three apartheid agencies – military intelligence, crime intelligence and the civilian National Intelligence Service - each transformed separately. There was a co-ordinating structure, the National Intelligence Coordinating Committee (NICOC), but the culture of the new agencies aligned at different paces with the values and goals of the new government.

By the end of 1994 policy and legislation were in place to amalgamate the national and bantustan agencies of the apartheid state with liberation movement intelligence departments, separating domestic intelligence functions, in the National Intelligence Agency (NIA), and foreign intelligence in the new South African Secret Service (SASS). There had been intense discussion and negotiation about amalgamation that ranged from high strategy focused on the character of the services to minute technical detail of who would occupy which position. Although liberation movement personnel were in the minority, the ANC took care to put them in a more strategic position compared with what happened in the military and crime intelligence structures.429

extensive discussion and debate and negotiation from the highest strategic level down to the minutest technical level

New forms of control and oversight included operational oversight by independent Inspectors General for each service; ministerial accountability; and parliamentary oversight by the Joint Standing Committee on Intelligence.

The new service was formally initiated in 1995, with a director-general from the ANC, Sizakele Sigxashe, a deputy from ANC heading NIA and a deputy from the apartheid NIS heading the new SASS. The service was launched with an ANC person, Joe Nhlanhla as de facto political head. He was made Deputy Minister of Justice (Intelligence Services) rather than a full minister because the constitution limited the number of ministers in the Cabinet of the Government of National Unity.

Although formally achieved, integration proved slow and uneven, with persisting mistrust between old and new order personnel, as well as some tensions amongst ANC personnel.

The quality of intelligence reports frustrated Mandela. Regular intelligence briefings sent to the president’s office were ‘like reading newspapers three days old’, according to Jakes Gerwel.430 The more substantial reports on particular issues were at times rejected with harsh comment by Mandela, in Cabinet431 or in meetings with intelligence officials. In one instance he had intelligence officials sent away from a Cabinet meeting because their report lacked information about a matter he had asked them to look into.432 On some matters, in particular to do with international developments, the politicians were better informed than intelligence reports produced by officers from the previous administration. When Alfred Nzo, the Foreign Affairs Minister, was handed a report on participants in the Burundi peace process, he dismissed it: ‘this report ii nonsense. ... I know these people. I lived with some of them in exile in Tanzania.’433

In cabinet meetings, have you seen him really lose it?

Distinguishing fact from misinformation proved a big challenge for the new intelligence service when former members of the services, or others with links into the new, fed elaborate reports of plots from right and left to destabilise or overthrow the government.434 The Meiring report was one such invention using the work of ‘information peddlers’, put together by elements in military intelligence which, General Nyanda told Mandela after the judicial commission had declared the report baseless, was one of the most backward and untransformed departments of the DoD. One is painfully aware of its unreconstructed thinking, operations and ideological weddedness to the past as shown by a great deal of one-sidedness and bias in favour of the old-friends of the SADF in analyses and reports on Southern Africa and a preponderance of phantom left wing threat reports compared to graver right-wing ones.

SASS played an unseen role in the background of Mandela’s international initiatives, working most directly with Thabo Mbeki. The new leadership of SASS shifted the balance of foreign intelligence from that of the old order, which prioritised Europe and the United States, to a perspective in keeping with the new foreign policy priorities. South Africa’s increasing involvement in conflict resolution, did much to promote that shift. As intelligence services do, SASS also played a ‘back channel’ role, whether to facilitate progress or mend fences. For instance, after Mandela’s explosive reaction to the execution of Ken Sarowiwa and others, intelligence officials were sent to Nigeria to facilitate interaction with the Nigerian government. Another task was easing relations with Egypt in the context of a fallout between Mandela and President Mubarak after the latter misled him in 1992 with a false promise to donate funds to the ANC.435

we posit a few theories why we think that a fraudulent report was prepared

SASS from very early on was very much involved in conflict resolution,

When Mandela officially opened the new building which housed the new agencies in 1997, he described it as an important milestone in the establishment of a new approach to intelligence in the service of democracy and development – but shared his worries about elements in the service.

The challenges facing democratic South Africa are without doubt different from the challenges of yesterday.

In the past, the single biggest threat to the security of our people came not from outside, but from our law-enforcement agencies including the intelligence services.

All of these structures formed an integral part of the oppression of the majority in our country.

Our new constitution does much to ensure that this never happens again.

In the first instance, we have established a democracy, with government which derives its mandate from the will of the people.

In this regard we have started the difficult but necessary task of changing the state, and the intelligence community in particular, into structures that serve the people rather than terrorise them; structures that protect the integrity of our country rather than destabilise our neighbours, structures that protect democracy rather than undermine it.

It is to ensure all this, that the Constitution further established the Office of the Public Protector, the Human Rights Commission and the Joint Standing Committee on Intelligence. As such, ordinary citizens are guaranteed protection against state abuse. …

Turning to the work of the services, he described their primary task as becoming ‘the eyes and ears of the nation’

We expect both NIA and SASS to help create the environment conducive for reconstruction and development; nation-building and reconciliation.

You are expected to be at the forefront of securing the peace and stability that is necessary for prosperity and equity.

Indeed, without a better life for all, any hope for national security would be a pipe-dream.

Our own history has confirmed that none can enjoy long-term security while the majority are denied the basic amenities of life.

We are also confident that you will continue to give valuable support to the police in the combating of crime, particularly organised crime.

He did not let the occasion pass without speaking of his concerns. The new buildings, he said, provided the intelligence services with excellent working conditions – but there was a price attached to their good fortune.

We will, more than ever before, continue to cast a critical eye on the quality of your products and the service you provide.

It must be said that there has been unevenness in the quality of your work, and at times firm action has been necessary for a more resolute effort to produce intelligence of value.

He referred to a recent spate of thefts from intelligence offices.

It is quite clear from the nature of these thefts that there are elements within your structures, linked to others outside, who are working with sinister forces, including possibly crime syndicates and foreign intelligence agencies to undermine our democracy.

If these forces had been more meticulous and surreptitious in their actions, we could have drawn solace from the fact that they respect our intelligence community.

But the blatant manner in which these thefts were conducted has sent a clear message of arrogance to us, that they can do anything with impunity.

They have, so to speak, thrown down the gauntlet.

These are forces that are bent on reversing our democratic gains; forces who have chosen to spurn the hand of friendship that has been extended to them; forces that do not want reconciliation; indeed forces that wish of us to apologise for destroying apartheid and establishing democracy.

But Mandela said he was confident the problems would be solved and that that there was movement ‘one step closer to making our intelligence services fit for our new democracy.’

The official opening of the joint Headquarters of the National Intelligence Agency and the South African Secret Service symbolises another giant step away from an era when intelligence structures were at the centre of division and conflict in our country.