General van der Merwe did agree to stay on, as head of the South African Police, which was dominant amongst the eleven apartheid police forces. Pending integration of these forces under a National Commissioner he chaired the Interim Board of Commissioners and effectively headed the country’s whole police force. But he never did become National Commissioner of the new South African Police Service.

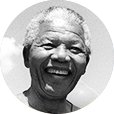

Foremost in Mandela’s mind when he met the generals just before the election was stability, not just for the election or to deal with the immediate right-wing threat. He foresaw the possibility that elements within the security forces could block or even reverse change. That was not just because they housed a significant right-wing presence. Fear of retribution for what they had done in the past could feed obstruction to change.

The country still depended for stability on forces steeped in the outlook of the apartheid system – but it also needed them to change in outlook and practice, to be committed to serving a democratic South Africa and to be seen as such by citizens. The way forward therefore had to bring those from the past as active custodians and builders of the future. Another consideration was that a lot of information about human rights violations had not been revealed, and an immediate shake-up of the security forces could see the evidence destroyed, depriving the government of information that would be crucial to understanding the past and making sure it was not repeated.393

Six months into the new government, in November 1994, the new Minister of Safety and Security, Mufamadi, asked Mandela to address the top police command. After a photo-opportunity for the media, he spoke to them behind closed doors, from notes he had prepared for the meeting.

he knew that there was a lot of information about atrocities’, all the violations of human rights, which had not been revealed

I welcome the opportunity to exchange views with the command structure of the SAPS. You are responsible for law enforcement. You can only achieve this objective if you receive the full support of Government.

I am here not as representative of any political party – neither the National Party nor the ANC – but as head of the Government of the country

I believe in a police force which is committed to serving the nation as a whole, not a particular political party.

I believe in a force that maintains the highest professional standards. Such high standards should be maintained even in the course of making a radical restructuring and reorientation of the police services.

We have to bring about such radical transformation, but we would like to do that with the full co-operation of the Commanding Officer of the Police and the entire Command Staff.

It would be regrettable if the perception is strengthened that you are opposed to such transformation, that you want to defend the racist nature of the force in which a white minority dominates, and where blacks are relegated to inferior positions.

You must not appear to be giving in to these changes only under pressure.

You must never forget that the changes that we are introducing in this country were brought about by the struggles of the oppressed people of our country, some of whom paid the highest price. Many of these died in police custody, and others were so tortured in detention that they are crippled for the rest of their lives. They will never allow, especially now that they are in power, for any Government agency or department to undermine their programmes to better their lives.

You must also not forget that the eyes of the world are focused on SA.

Notwithstanding the brutality of the apartheid system generally, and that of the police in particular, during the run-up to the elections I urged my people to forget the past, to work for reconciliation and for nation-building.

With a few insignificant exceptions the entire country has responded marvellously to this message, black and white, Shangaan, Venda, and Sotho, Afrikaans and English speaking South Africans are now working together to build a new South Africa.

The police must not appear to be opposed to this movement and spirit, paying only lip service to the idea, whilst working day and night to undermine what we are doing.

Not only did I appeal to the nation as a whole to change their attitude towards the police, I took certain steps quietly to ensure that the new SA comes peacefully:

(a) I met Gen V. d. Merwe, some months before the elections;

(b) I addressed the Command Staff of the SADF;

(c) I addressed the Command Structure of the SAP on16 January 1993;

The SAP have responded very well. They made a formidable impression on the day of the inauguration, as did the SADF. The Generals of SAP must not appear to be against this development.

Ghosts of the past can continue to haunt us if we do not become a visible part of the current changes. Hit squads are still a disturbing feature in the crime situation; and the failure of the SAP to bring them to book is a source of great concern to me.

Mandela listed things troubling him: lack of disciplinary action when police were shown to have been involved in military training of Inkatha members; not searching illegal IFP training camps; and not responding to open defiance by IFP members carrying illegal weapons. He cited the lack of action against Eugene Terre’Blanche who led the AWB in action that killed people in Bophuthatswana before the elections, contrasting that it with ‘the sharpness and almost vicious manner in which SAP acts against ANC’. He noted that some police were involved in crime. He referred to the impact of high crime levels on investment, and concluded with concern about the working conditions of ordinary members off the police.394

The high priority he accorded these issues coloured Mandela’s close interest in the police throughout his presidency. He always attended meetings of the cabinet committee on security and intelligence.395 He interacted frequently with police at all levels, as Sydney Mufamadi recalls. Forthright talk behind closed doors was matched by public appeals to communities to support the police who, he said, were making an effort to embrace the new South Africa.

Besides meetings that I would suggest he should have with members of the police service, senior and junior, he would also on his own initiative invite members of the police, for example when he is on holiday in the Eastern Cape and he invites members of the former Transkei police or Ciskei police just to want to know from their own perspective what they think about their changing situation and give advice where he felt it was warranted, encourage them to stay focused on their work. …

There were times when a particular form of crime would show up as a national priority crime, such as the cash in transit-robberies that emerged at one point as a disturbing trend of seriously organised crime carried out by people who in some instances had military training. We established a special unit to investigate that and once he became aware of it he would then say, ‘These people have been given a very challenging task, can I meet them and hear them out. What do they think about the task that we have given them? Have we given them enough resources to do their work?’ He would encourage them. When they made breakthroughs, he would invite them and congratulate them for the work well done, and so on.

But at all times, even as he was talking to them in positive terms, encouraging them to do more of the good work they were doing, he would always draw a line about the things he doesn’t want to see a repeat of, things that belong to the past. … If you look at his notes for some of the speeches he made behind closed doors to the police generals, you will see that the was conscious, fully conscious, of his presidential responsibility, he knew when to say what to them, he wouldn’t just repeat in public everything that is said to them, because he was not grandstanding, he was making statements based on principle.396

victims of violence sometimes just went round to his house and confronted him with the helplessness that you would then feel

One of those meetings Mandela himself initiated during the December holiday period he spent at his Qunu home was with Eastern Cape officers, in 1996.

A report released by the National Information Management Centre of the SAPS showed that 1996 saw a reduction in levels of serious crime; crime categories which reflected a reduction include such violent crimes as hijackings, armed robberies, politically motivated violence, murder & taxi violence.

Members of the SAPS need to be congratulated, for the reduction in levels of crime is a result of hard work and sacrifices which they made & continue to make.

Notwithstanding the many problems which some communities in the Eastern Cape still have, for example taxi violence in Port Elizabeth, violence in Qumbu, Tsolo, Mqanduli, as well as gang related crime in the Northern areas of Port Elizabeth, the Eastern Cape as a Province, experienced such a decline in levels of serious crime in 1996.

This is by no means a small achievement, given the fact that the police had to attend to the task of fighting crime, whilst at the same time they were attending to the task of restructuring the police service and amalgamating three agencies within one province – the Transkei police, the Ciskei police & the then SAP.

Those who are committed to serving the community need not be discouraged by the fact that we still have a few elements within the SAPS who do things which bring the police service into disrepute. The fact that such elements are often exposed by their own colleagues, will in the long term, convince the communities that the police have irrevocably broken with the past. …

One of the problems which dogged the province is the corruption which pervades the various state departments. The fact that some of the high profile cases of theft of tax-payers money remain unsolved, does not contribute to a good public image of police. It is important to bear in mind that the credibility of the SAPS will derive from the feeling that the SAPS is committed to solving problems experienced by our people.

For its part, Government is committed to doing everything in its power to equip the police to do their work. Despite severe financial constraints, we make sure that as we buy new vehicles, distribution is now skewed in favour of the historically disadvantaged areas. In the case of the Eastern Cape, the former Transkei and Ciskei areas were given preference over the areas which in the past were under the jurisdiction of the SAP and therefore more privileged, for example, a distribution of 80% in favour of white areas. 20% in favour of Black areas.

In terms of a Presidential project we have also prioritised the upgrading of dilapidated police stations which are located in this part of the Eastern Cape.

The National Commissioner was asked to give us a proposal which will enable us to consider lifting the moratorium on recruitment. We are determined to give the Commissioner the force levels necessary for him to effectively deal with the problem of crime. However, we also want evidence of the SAPS’ good faith in attempting to utilise the resources at its disposal most effectively.

The reason why in the first place we imposed a moratorium on recruitment is that we were not satisfied that personnel as well as other resources at the disposal of the SAPS were deployed prudently.

By the time of this meeting, the eleven apartheid police forces had been amalgamated into a new national South African Police Service (SAPS), with a new National Commissioner who had been in his post for some two years. General Van Der Merwe had taken early retirement in January 1995 just a few months after he had been requested by Mandela to stay on.

Mandela’s request to van der Merwe and others to stay on was meant to assure them, and those they led, that they were not going to be persecuted for things they had done in the past. There was a place for them in the new South Africa as long as they would participate in building the future and work to ensure that what had happened would not happen again. However van der Merwe showed little enthusiasm for the investigations into the continued existence and operations of hit squads or the establishment of a Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) which was expected to expose structures continuing to foment violence, (See section on TRC). As confidence between the general and the minister dwindled, Mandela concluded that he could not appoint van der Merwe as the first National Commissioner (in line with the new South African Police Service Act).398

...assure them that he really wants an inclusive arrangement in which they will have a place and that the time to earn that place was then...

It was under those circumstances that George Fivaz became the new National Commissioner. Mr Sydney Mufamadi became the Minister of Safety and Security.

The two were the foremost pioneers in the creation of a new South African police force dedicated to the service of all our people regardless of colour or creed. In the National Crime Prevention Strategy (NCPS) which came out in 1996, and in other policy documents that followed, they candidly analysed the formidable challenges facing the Department of Safety and Security.

They pointed out that the first democratic elections in 1994 did not bring a system of policing which was well placed to create a legitimate police service out of the eleven police forces constituted under apartheid.

They reminded us all that policing in South Africa was traditionally highly centralised, paramilitary and authoritarian. While these characteristics ensured that the police were effective under apartheid in controlling the political opponents of the government, it meant that they were poorly equipped for crime control and prevention in the new democracy.

Under apartheid rule, they stressed, the police force lacked legitimacy, and functioned as an instrument of control, rather than as a police service dedicated to ensuring the safety of all citizens. Thus historically, the police had had little interest in responding to crimes in the black areas. In 1994, as much as 74% of the country's police stations were situated in white suburbs and business districts.

Police presence in townships was used to anticipate and respond to collective challenges to apartheid. This mode of policing necessitated the mobilisation of force requiring skills and organisation very different from that needed to police a democratic order in which government seeks to ensure the safety of all citizens. That inheritance had a number of important consequences which weakened the ability of the Department to combat crime.

The study pointed out that the authoritarian policing had few (if any) systems of accountability and oversight, and did not require public legitimacy in order to be effective. Thus with the advent of democracy in South Africa, systems of accountability and oversight were not present.

New mechanisms such as the Independent Complaints Directorate(Directorate (ICD) – a complaints body tasked with investigating abuses within the SAPS, situated outside of the police, but reporting directly to the Minister – provided the means of limiting the occurrence of human rights abuses.

The study contends that the South African Police Service had not had a history of criminal detection characteristic of the police in other democratic societies. The collection, collation and presentation of evidence to secure the prosecution of criminals was weakly developed in many areas. This was reflected by, among other indicators, the training levels and experience of the Detective component of the SAPS.

In 1994, only about 26% of detectives had been on a formal investigation training course, while only 13% of detectives had over six years experience. In any event, those detective skills present in the police force before 1994 were concentrated in white areas.

According to the study, the problems of criminal detection were mirrored in the area of criminal intelligence. Intelligence gathering structures were orientated towards the political opponents of the apartheid state. Consequently, crime intelligence, particularly as it pertained to increasingly sophisticated forms of organised crime, required immediate improvement.

A concentration on policing for purposes of political control meant that prior to 1994 - and in contrast to developments in other societies – the understanding and practice of crime prevention was poorly developed in South Africa.

The NCPS was the most important initiative aimed at achieving sustainable safety in South Africa. It had two broad and interlocking components, that of law enforcement and that of crime prevention, particularly social crime prevention.

The study adds that law enforcement initiatives will be weakened if conditions in which they are carried out continue to generate high levels of criminality. International experience had shown that sophisticated crime prevention strategies had only a limited effect when such institutions of policing and criminal justice were poorly developed.

What was required were social crime preventing programmes which targeted the causes of particular types of crime at national, provincial and local level. Such an approach also recognised the impact of broader government economic development and social policies for crime prevention. The effective delivery of basic services such as housing, education and health, as well as job creation, had in themselves, a critical role to play in ensuring living environments less conducive to crime.

I have summarised this frank and objective police study to show how Sydney Mufamadi and George Fivaz accurately described the type of police force the new South Africa was inheriting from the apartheid regime. These are the well-considered views of two eminent and courageous leaders with undisputed credentials in their commitment to the country.

The crisp message from them was that we need a new police force, totally different from the one that served the apartheid state, if we are to succeed in reducing the unacceptably high level of crime ravaging the country. Only a force stripped of its paramilitary and authoritarian characteristics and properly trained in the modern methods of policing in a democratic order could help South Africa to achieve this object.

Commentators of integrity would complement the Department of Safety and Security for their analytical ability and vision. No honest analyst, black or white, could expect this goal to be achieved within a period of seven years.

In his budget speech to the National Assembly on 28 May 1998, Sydney Mufamadi quoted a telling passage from the South African Institute of Race Relations Survey [of 1993/94] which observed:

‘According to the annual South African Institute of Race Relations Survey, murder and armed robbery, as well as attacks on the elderly and on policemen, have increased dramatically, while white-collar fraud had also risen sharply in1992. The Minister of Law and Order, Hernus Kriel, said in Parliament in May 1993 that more than 20 000 people had been murdered in South Africa in political and criminal violence in 1992. There were 38 000 rape cases in South Africa every year and 95% of the victims were African. In the ten years from 1983 to 1992, the murder rate increased by135%, robbery by 109%, house breaking by 71%, car theft by64%. However, many crimes were unreported.’

Sydney Mufamadi added that that indeed was a picture of an escalation of serious crime which demonstrated grave geometric continuity.

It is against this background that the achievement of the government in transforming our police force must be seen. It must, however, be conceded that even during the darkest moments of apartheid there were many police, black and white, men and women, of the highest calibre, who were professional in their duties, and who tried to the best of their ability to serve all sections of the population without discrimination.

But these were few and far between. They were the exceptions rather than the rule.

The overwhelming majority fully accepted the inhuman policies of apartheid, and served as the instrument of the most brutal forms of racial oppression this country has ever seen. Some of these men and women are still members of the present force, occupying strategic positions, and obstructing in countless ways the creation of a new police force.

Nevertheless, both Sydney Mufamadi and his successor, Steve Tshwete, George Fivaz and the present National Commissioner, Jackie Selebi, have made unprecedented progress in creating a new force capable of policing in a democratic order, and insignificantly reducing the high levels of crime.

On 24 May 1997, and after discussing the matter with me, Deputy President Mbeki announced the appointment of Mr Meyer Khan, Group Chairman of the South African Breweries Limited, to take on the position of Chief Executive of the SAPS for a two year period. The Deputy President explained that that was a new civilian function calculated to direct and accelerate the conversion of the SAPS into an effective law enforcement and crime prevention agency. Mr Khan would report to Safety and Security Minister, Sydney Mufamadi.

The Deputy President added that our selection of one of the private sector's toughest and ablest manager – and his willingness to answer the call – underscored the new era of partnership between the public and private sector to end the scourge of crime.

National Commissioner Fivaz would thus be freed of the administrative burden within the SAPS, and would be able to concentrate his total energy on managing and controlling the pure policing operations of the service.

The goal, the Deputy President said, was to put the police back on the frontline, and make sure that they were equipped with the right skills and resources to do their job well.

But the partnership between the government and the private sector actually started a year earlier with the establishment of a non-profit organisation, Business Against Crime (BAC). The prime aim of the organisation was to contribute to the government's crime-combating strategy, policy and priorities, and to transfer much needed technology skills to government.

This partnership has been hailed as one of the best practise of its kind in the world. The NCPS was the first initiative of this partnership. After the engagement of Meyer Khan, other full time business executives were appointed and funded by the business community.

These helped to modernise the criminal justice system, combating commercial crimes, organised crime and the installation of electronic surveillance with remarkable success. In one area, electronic surveillance resulted in an 80% reduction in crime, increased conviction rate in cases where crime had been committed, a 90%decrease in the number of police personnel required to patrol the area, and an average response time to incidents of less than 60seconds.

This sober assessment comes from Business Against Crime, an important section of the community which has spent considerable resources, time and energy to improve the quality of our police services.

I asked Meyer Khan for a report on our agreed strategy to reconstruct the SAPS into an effective law enforcement agency. He responded on 02 July 1998. Among the structural focus areas he dealt with was the enforcement of the newly launched Code of Conduct with a view to, over time, changing the conduct and behaviour of the police.

The golden thread that flew from that Code, Meyer Khan reported, was one of caring. Care for your country, care for your communities, care for your colleagues, care for your asset and, above all, care for your reputation.

He pointed out that he had by then been in office for eleven months and had no regrets about his appointment. He believed that our new strategies were as good as one would hope to find. He was heartened by the fact that our statistics indicated clearly a stabilisation and mild decrease across the board in terms of all the serious crime in our country. He considered this to be fairly remarkable against the background of a deteriorating external environment of no economic growth and greater joblessness. In addition, the very high and speedy arrest rates by our detectives in respect of high profile crimes that so damage the morale and reputation of our country certainly indicated that the SAPS still had the skill and dedication to compare with the best in the world.

However, he placed on record that the increase in the police budget of only 3,7% in monetary terms and on a comparable basis, he found difficult to comprehend. Particularly against the background that fighting crime is recognised by every South African, as well as by international opinion, as the foremost, if not the only priority, in order to create an environment for our democracy and economy to flourish.

He regretted that a reduction that year in real terms of at least 4%in police spending would inevitably impede even the most basic policing that our people were entitled to expect, and would most certainly place our medium-term strategy of reconstructing the SAPS in serious jeopardy.

But the Deputy President, Business Against Crime and Meyer Khan, acting independently of one another, virtually reinforced the assessment of Sydney Mufamadi and George Fivaz in analysing the formidable challenges facing the Department of Safety and Security in their efforts to transform the SAPS from an illegitimate and discredited service to a credible and efficient force in a democratic South Africa.

They all spelt out the changes required and in due course assessed the results of such initiatives, the cooperation between the SAPS and the masses of the people, and the gradual decline in the levels of various crimes. Their performance and achievements left all of us proud of our country, of our comrades, our police and of ourselves. We were exuding with confidence and optimism.

Yet opposition parties, some of whom created or inherited that authoritarian and repressive force, and others who condemned white supremacy, but opposed every legitimate action used by the oppressed to liberate the country, now accuse the government of being soft on crime. Hardly do they ever praise the government and business for their excellent performance and for the efficient and devoted SAPS now bequeathed to our country.

The reason for this peculiar attitude on the part of some South African politicians is not far to find. As pointed out in a previous chapter, the white minority has ruled South Africa for more than three centuries.

Some of them, drunk with power and without vision, never imagined that they would in their lifetime, suffer the trauma of losing that political power to a majority they were taught from birth to despise.

Even in the face of the far-reaching peaceful transformation that has taken place, plus the zeal with which the ruling party has promoted and implemented the policy of reconciliation, the background, education and political training of some sections of the opposition make them deaf and dumb to what is currently happening in our country.

We have shown in a previous chapter that since April 1994 our voter support has increased considerably in both the general and local government, as well as in the mega cities. All this information has made no impression whatsoever to some members of the opposition. They still harp monotonously on false propaganda which nobody else, except themselves, believe in. They criticise the government for lack of delivery, predict a split in the Alliance and accuse the government for being soft on crime. If there was a grain of truth in all these accusations, why then would our support continue to grow as it has done over the last seven years?

The so-called New National Party is on the way out, never to return. They have no leader of the calibre of former President De Klerk who had the courage and vision to take the right turn when he reached the cross-road.

But, South Africa has produced great liberals who courageously condemned apartheid. Although they disagreed with our methods of political action, and insisted that we should confine ourselves to purely constitutional forms of struggle, they were far less arrogant and destructive than some of their heirs.

Think of internationally famous liberals like the veteran human rights campaigner, Helen Suzman, her compatriots, Sheena Duncan, Irene Menell, Colin Eglin, van Zyl Slabbert, Zac de Beer, the Black Sash, religious leaders, academicians and white students in English universities and a host of other individuals across the length and breadth of our country who consistently called for the restoration of human rights to all South Africans.

Their historic contribution to the fight against all forms of colour discrimination is in danger of being defaced by reckless individuals, who put their sectarian interests above those of the entire country; who are determined to use all means, fair and foul, to discredit a strong and popular government which is succeeding in fundamentally bettering the lives of all South Africans.

The new generation of South Africans, who are now filling positions of leadership in government and society, may dismiss the past achievements of our liberals because of the unpatriotic and morally offensive behaviour of some of the present liberals, who are not only attacking the ANC and the government, but who are also denigrating the visible achievements of our present police force.

The truth is that the Congress Alliance – consisting of the African National Congress (ANC), the South African Communist Party (SACP) and the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) – and other progressive forces are jointly building a new South Africa. Contrary to the prophets of doom who predicted bloody civil war before we could have a transformation, we have had in fact a peaceful one which has touched the international community to hail us as a miracle of the world.