General Meiring’s unqualified commitment to serve a democratic government seemed a promising start. His recent conduct had given Mandela some reason for confidence. The army had helped secure the 1994 elections and the inauguration.

But transformation of the defence force proved turbulent.

The South African Defence Force (SADF) of the apartheid government and the defence forces of the four ‘independent’ bantustans – Transkei, Venda, Bophuthatswana and Ciskei – as well as the KwaZulu Self-Protection Force, had to be made into an integrated South African National Defence Force (SANDF) together with those they had been taught to regard as the enemy, the forces of the liberation movement, the ANC’s Umkhonto weSizwe and the PAC’s Azanian People’s Liberation Army. And once all these forces were included, the new SANDF would then have to be rationalised and downsized.

There was an initial meeting in May 1990 in Lusaka of SADF officers with representatives of MK,400 and further meetings during 1992,401 but the first practical engagement about forming the South African National Defence Force was in April 1993 a year before the election when senior ANC military and intelligence leaders met the top five of the defence force – they were sent by Mandela as president of the ANC, who told them, ‘These people want to talk’.402 Even before that there had been exploratory meetings, reflecting an acceptance on the part of the government, military and intelligence that the ANC would be the future government.

During the time of the TEC a Joint Military Coordinating Committee (JMCC), worked in detail on plans for integration that would create a single defence force from midnight of the day the election started. It was chaired by General Meiring and had representatives from both the SADF and liberation movement forces. By that time Meiring’s retention as head of the new SANDF was agreed in principle, part of what the ANC envisaged as a two-phase process of transition.

We were sent by the president of the ANC who said, ‘These people want to talk.'

To prepare for integration the ANC briefed MK cadres in the camps and held conferences in the country, to explain and discuss the process. Mandela attended some of the conferences, among other things advising those who volunteered for demobilisation, not to ‘eat the money’ they would receive – to little avail in most cases.403

Mandela was involved in the internal meetings, conferences we had

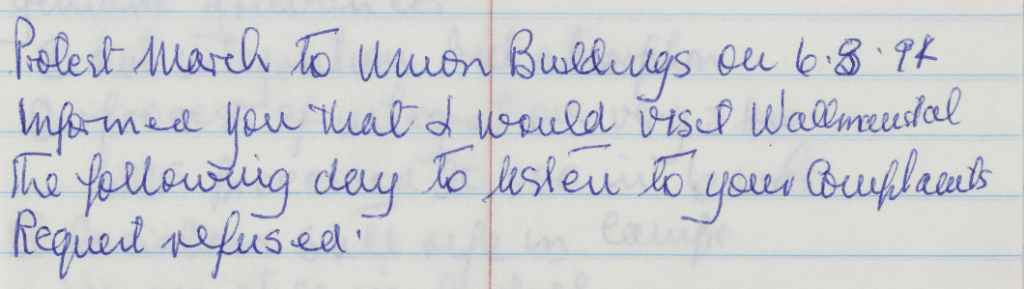

Despite the preparation, integration soon ran into suspicion and conflicting expectations fostered over years of enmity. Much of it was set at the Wallmansthal military base 50 km from Pretoria where, days after the election, the car of two MK generals visiting the base to deal with complaints was stoned by former MK members. A few months later some 500 members of MK marched from the base to the Union Buildings. They arrived late at night and demanded to see the president. He came immediately from his residence and after listening, acknowledged their grievances as genuine.404

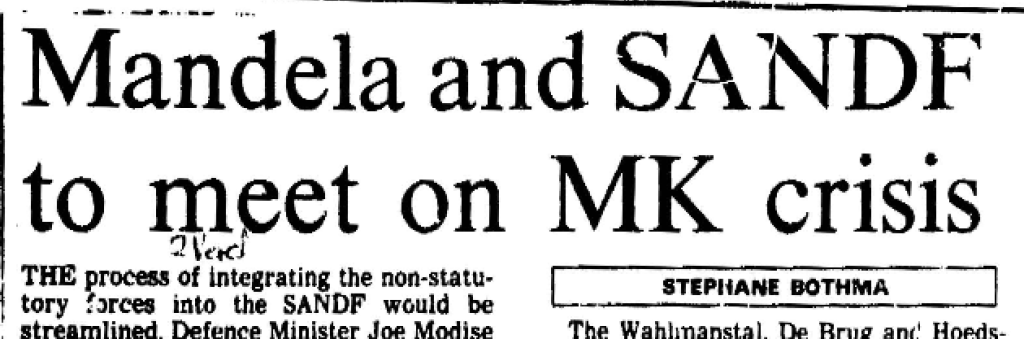

He discussed the matter with General Meiring, with the acting chief of staff, Siphiwe Nyanda, and with the minister of defence, Joe Modise. He interacted further with MK members. He met SANDF Command Council and urged them to remedy the genuine grievances, namely: that the members of the liberation forces (and bantustan armies) were being accommodated rather than integrated; that the process was very slow; that racism was still rife in the camps; and that living conditions were very bad.405 He followed that up with a visit to Wallmansthal to address the former MK members there. Half the 7 000 soldiers from there and elsewhere who had gone absent without leave were still refusing to return till their issues were resolved.406

Addressing the MK cadres at the base, he reminded the soldiers of MK’s history, why it had been formed and of its proud record, of which, he said, they were expected to be custodians. After listening for two hours to their concerns he put a firm message to both protestors and commanders. While the soldiers’ grievances were legitimate, they were pursuing them in a way that was unacceptable in soldiers. They had a week, he said, to return to their bases at their own cost and submit themselves to SANDF discipline – those who were not back by then need not return. To the SANDF leadership he said the integration process had to speed up – adding that he was confident that General Meiring and the commanders were committed to making a success of integration.407

Most of the soldiers returned. But a number didn’t and rumours that some were threatening armed protests highlighted a concern that demobilised soldiers – from either side - could turn to crime or political destabilisation. It was a worry Mandela voiced in a media interview in 1996.

We have a big army of about 90 000. We don’t need even half of that. We need far less because we have no enemies.

But assuming we reduce it by half this year, there would be another 45 000 people unemployed. We already have five million unemployed.

We then create a great deal of bitterness on the part of people who are trained to use arms. And with arms circulating in this country almost freely, that would be a dangerous thing to do.

When in 1995, General Malan, the minister of defence in the apartheid government, was arrested and charged with responsibility for a massacre at KwaMakutha in Natal in 1987, Mandela took action to preempt the anticipated opposition reaching a dangerous level. He explained to the ANC NEC what he was doing and underlined the seriousness of the situation as he saw it.

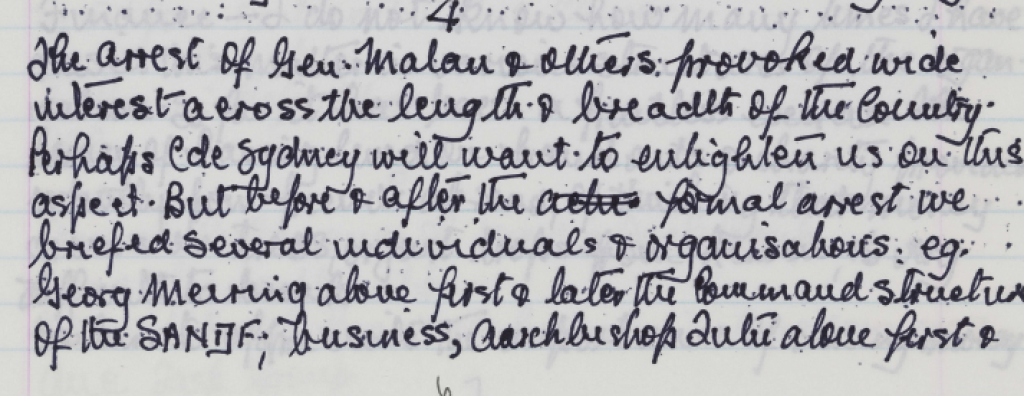

The arrest of Gen Malan & others provoked wide interest across the length & breadth of the country. Perhaps Cde Sydney will want to enlighten us on this aspect. But before and after the formal arrest we briefed several individuals & organisations: for example George Meiring alone first and later the command structure of the SANDF; business, Archbishop Tutu alone first and thereafter the SACC, Bishop Lekganyane, the DRC (Dutch Reformed Church), political scientists from all our universities, with the exception of Stellenbosch and PE [Port Elizabeth]; the 26 teachers organisations, the FF [Freedom Front] and PW Botha.

Role of PW Botha and Gen. Viljoen must not be underestimated. In spite of what PW Botha said at the press conference after our meeting, he & Viljoen have helped us to margnalise the right wing. Won’t discuss any details in this regard.

When he spoke to the SANDF commanders, he brought a terse message.

He didn’t allow any questions, just came there as Commander-in-Chief. He had said he wanted to come to a Monday meeting. The essence of what he said is this: ‘We have gone through a difficult period of change. Our people fought for this democracy that we now enjoy. It is at a tenuous stage and if there are people who want to undermine this democracy and reverse things, the South African people with their bare fists will smash those tanks. They will not be intimidated. They will defeat whoever wants to undermine this democracy that we are enjoying.’410

The message was the same as his words to P W Botha whom he went to see at his home:

They have now tasted freedom, and I can assure everybody that they are so determined to keep their independence, their freedom, that they will pick up ordinary stones and bring down bombers and crush military tanks; so determined they are.411

If integration caused some unhappiness in liberation ranks in the early stage, the later rationaliisation and downsizing caused some unhappiness on the other side. Initially, like the rest of the public service, the Sunset Clauses assured those in the military of their jobs for a while. Once personnel from the liberation movement had moved into leadership positions they were able to determine, during the rationalisation phase, who would fill key functions in ways that would help give shape to a defence force geared to democratic ideals and objectives.412

An issue of a different kind – though not unrelated –brought a new challenge, this time with a grievance from the old-order. As the White Paper defining the future national defence force was being developed, the question arose: what was to be the language of instruction, training and command? The draft proposed that there should be just one language for these purposes – and that it should be English. After a robust engagement on the issue with the parliamentary portfolio committee on defence Meiring complained to Mandela – perhaps as much for the unaccustomed robustness of the engagement as the content.

when we moved to democracy the security forces were assured of their position until they were pensioned off

Mandela took the issue up both with parliamentary caucus (see Chapter 7) and in public. When he met a group of Afrikaans women at his official residence, with media present, he said the committee’s view was wrong. Tampering with a group’s language would ‘reduce the country to ashes’ and it was not the policy of the ANC or the Government of National Unity. If Afrikaners were ready to accept the challenges of the new South Africa he would have confidence in their loyalty and would ‘protect their precious cultural heritage as if it was my own’. He said he had told General Meiring to ignore the proposal.413

The Portfolio Committee stood by its proposal and left the final word to the minister and Cabinet. The proposal that English would be the only language was no longer there when the White Paper went to the Cabinet on 8 May 1996. Instead it read, ‘The SANDF shall respect the constitutional provision on language and shall endeavour to cater for the different languages of its members. Instruction, command and control shall be conducted in a language that is commonly understood by all.’414

But there were still bigger and more dangerous issues at play which would in time bring about General Meiring’s resignation.

Although amalgamation of intelligence agencies brought them in theory under the control of a new national intelligence service, military intelligence continued to harbour elements pursuing agendas from the past. The first incident, three months into the new government, was an attempt to put pressure on the minister of defence with a threat to publish names of ANC members now in government who had allegedly been informers to the apartheid regime.415 Then over the next three years an elaborate report was created within military intelligence sketching a plan to disrupt the 1999 elections and bring down the government. Among other things the report claimed was that the plans involved the person most likely to succeed Meiring, General Siphiwe Nyanda. When the report reached General Meiring in 1998, he took it to the president. Mandela was skeptical because it was so implausible and because it named people likely to take senior positions when old order generals moved on.

Mandela briefed Parliament in April 1998 when he opened the debate on the President’s Budget.

Several recent developments have underlined the strength of our democracy. Media reports suggesting that a coup plot had been uncovered have turned out to be essentially without foundation and based on the fulmination of an active imagination.

It may be well to take this opportunity to brief hon members on the basics concerning the SA National Defence Force report which I received on 5 February, and which had the title ‘Organised Activities with the Aim to Overthrow the Government’. Initial consultations within Government raised questions about the report's reliability and lack of verification. These were still in progress when a leak of some of its contents made it necessary to establish, with urgency, the reliability of the process of its compilation, verification and subsequent handling.

The commission of inquiry appointed for this purpose, reported to me at the end of March. The intelligence report made the following claims: That an organisation called Fapla ...which stands for Force African Peoples Liberation Army, had existed since 1995 and aimed to subvert the 1999 general elections, and that it aimed to do so by assassinating the President; murdering judges; occupying Parliament, broadcasting stations and key financial institutions; and orchestrating generalised disorder over a period of some four months before the elections.

The culmination of this would be a campaign of attacks in which the present order would collapse, and power would be handed over to the coup leaders. Some 130 people are named in the report as the alleged organisation's members, leaders or supporters. They include very senior military personnel, political figures and others.

The commission's main conclusions are as follows. The report was without substance and inherently fantastic. All the witnesses interviewed were sceptical about the existence of Fapla. Even those compiling it appeared not to have taken it seriously. No serious attempt was made to keep the alleged plotters under surveillance and no attempts were made to properly authenticate the report.

Those responsible for compiling the report over three years failed to share it with the appropriate authorities, including the SA Police Service and the National Intelligence Co-ordinating Committee. The commission was critical of steps taken to keep the report safe and prevent leaks. Those responsible for compiling and handling the report did not communicate it to the Ministers responsible for intelligence and for safety and security, who only gained access to it from the President after he had received it from the Chief of the SANDF.

An allegation concerning a particular officer was communicated by the Chief of the SANDF to the Minister of Defence, but not the extent of the allegations, the identity of other senior officers alleged to be involved, nor the details of the conspiracy. The Minister of Defence said that he was not prepared to communicate an uncorroborated allegation to the President.

The commission concluded that such a report should not have been communicated to the President in the way it was. It also commented on the extraordinary procedure of a direct communication to the President and a deliberate avoidance of furnishing the report to any other officials. The commission recommended that the security agencies should investigate why the omissions and failures in the processing of the report took place and what could be done, if necessary legislatively, to avoid repetition in the future.

I acceded to the request for early retirement by the Chief of the SANDF, as it was an act which put the national interest and that of the SANDF above his own. The leakage of the report and the critical comments of the commission of inquiry over its compilation and transmission clearly put the General in a difficult position in his relationship with the senior officers mentioned in the report and with his commander in chief, the Minister of Defence. Such a bold, though regrettable, step was therefore clearly warranted.

Mandela wanted the public to be well-informed about the matter and dealt with it at some length.

In accordance with accepted norms and practices concerning such information, neither the original military intelligence report nor the commission of inquiry's report have been made public. That approach is all the more compelling given that we are speaking of a report that is untested and inherently fantastic. It would be the height of irresponsibility for any government to peddle untruths and fabrications about people whose reputation could be harmed, despite the lack of truth.

The public has a right to know that such matters as this are addressed thoroughly and scrupulously through processes in which they can have confidence. The commission of inquiry fulfils these requirements. The briefing of the parliamentary committees elaborates the process.

I have also offered to release the commission's report, with the removal of names of sources and other individuals mentioned, to the Joint Standing Committee on Intelligence. But we have gone further still. In order to allow broader oversight, the reports were made available to the leaders of the opposition parties.

It is instructive to note that it is those who opportunistically refused to look at the report who continue to call for its publication. At the same time they use the fact that they have not seen it to raise doubts about the Government's trustworthiness.

This is a dangerous game to play with our intelligence services and raises the question of whether the legitimacy of the Government is accepted by such people, or maybe it is simply a reckless pursuit of party advantage, bringing self-appointed champions of democratic conventions close to abdicating their responsibility as political leaders. I myself, in dealing with this matter, have sought to act according to the assumption that all of us in our respective political parties share a common national purpose.

Mandela had announced Meiring’s resignation two weeks before he briefed parliament, after he had received the commission of inquiry’s report.

I accepted his decision to step down with regret because he is an officer I hold in the highest regard because of the invaluable service he has rendered to the South African Defence Force and then to the South African National Defence Force and to the country and to me personally. Over these four years we formed a very close relationship in which I regarded him as one of my closest friends.418

By the time Meiring resigned and his place at the head of the defence force had been taken by Siphiwe Nyanda, the 1996 Defence White Paper and 1998 Defence Review had created a policy framework for the defence force in a democratic South Africa, defining the function and strategic doctrine of the new defence force, including how it should be equipped for its new posture and roles.

A defence secretariat was established, to reinforce civilian control. The principal function of the defence force was defined as self-defence, with regional and continental cooperation defined as a secondary role. That order of priorities reflected in part a need to convey a break from the apartheid regime’s use of military power to impose its interests on the Southern African region. A decade later, when South Africa had become an integral part of the Southern African Development Community, the order of priorities was reversed. The framework also provided for support for police operations against crime and included a requirement for the defence force to contribute to reconstruction and development.

An aspect of the Defence Review that captured public attention when Cabinet adopted it was a decision in principle to re-equip the defence force.

When the new government took office a purchase of corvettes from Spain was in progress. At the ANC Cabinet Caucus the night before the first Cabinet meeting since the inauguration, Joe Modise, the Minister of Defence, told the meeting the President had said he should tell them that the Corvette contract would be cancelled419. This was because it was necessary to look at the needs of all the arms of the defence force, as a whole rather than just one service. 420 The following day the Cabinet agreed to wind up the process.

The review of the defence force’s role and needs for equipment took nearly three years. Mandela tracked the review each year as he opened Parliament. In 1996 he anticipated imminent completion of the process:

we were waiting to start the meeting. He and Joe Modise weren’t in the room.

There is a national consensus that our Defence Force requires an appropriate capacity and modem equipment. We welcome the fact that debate on these issues is nowS finding rational reflection in the discussions around the Defence White Paper and the National Defence Review.421

In 1997 he foresaw further public debate.

Debate will continue this year on the White Paper and the Defence Review, but what is critical is to move towards practical implementation. One of the issues in this regard is the Defence Force's equipment requirements. The question here is not whether, but how, to meet these requirements and how much the country can afford. As Commander in Chief, I wish to emphasise that we shall not shirk our responsibility to the Defence Force.422

A year later he welcomed its conclusion

We are proud that after a year or so of healthy and informative debate; we can now start the protracted process of re-equipping our National Defence Force.423

And in 1999, opening Parliament for the last time:

We wish to assure members of our defence force that the nation is behind them in their endeavours. We remain committed as ever to equip the force in a manner that ensures its effectiveness and adds value to the economy.424

Although final decisions on the acquisition were taken immediately after the 1999 elections, most of the work had been done during Mandela’s presidency. Parliament had In April 1998, adopted the defence review’s recommendation that the defence force needed to acquire new equipment to meet its constitutional obligations, in terms of a defence force design which provided ‘the minimum force level that can be maintained as a growth core, in accordance with the core force approach’ that prioritised self-defence. ‘The absence of any immediate military threat to South Africa, the low probability of a significant threat within the foreseeable future, the reductions in the defence budget since 1989 and the likelihood that the budget will remain restricted for some time, have created a situation where the maintenance of extensive military capabilities is neither necessary nor affordable.’425

Given the scale of expenditure, the Cabinet consolidated the procurement into a single package, known as the Strategic Defence Procurement Package. The decisions on who should get the main contracts were taken by the Cabinet and a special interministerial committee, made up of the ministers of finance, defence, public enterprise and trade and industry, and chaired by then Deputy President Thabo Mbeki. The committee adopted a rule that it would not interact directly with any of the bidders, and there were four independent evaluation groups. Cabinet decided on the primary contractors, who would in turn be responsible for engaging the secondary contractors they would need to fulfil their obligations.426 ]

Although public and media attention was fixed on the difficult moments of integration and transformation of the defence force, by the end of the first five years it was in quite different shape from its predecessor and occupied an altogether different position in the South African nation.

Integration and rationaliisation had produced a defence force about 40 per cent of which came from liberation movement and bantustan forces.427 Recruitment of black youth into the voluntary part-time force further increased the numbers of new entrants.

The SANDF had earned recognition as a contributor to regional cooperation for peace and stability, through its participation in the SADC intervention in Lesotho, initiating the involvement in peacekeeping activities on the continent that were to become a key element of its principal functions.

A camaraderie was developing between soldiers from the different forces that had been in hostilities. And the army’s support for police in fighting crime was seen as supportive of communities in contrast to the apartheid army’s unwelcome presence in townships. A survey by the Human Sciences Research Council in 1999 found trust in the Defence Force among Africans at 62%.