At play in relations between Mandela and De Klerk were two kinds of factors

On the one hand, there were the ambiguities of an opposition party in a constitutionally enforced coalition that operated only at Cabinet level. De Klerk had carried only part of his National Party Cabinet and constituencies with him in the final stages of negotiations.161

From the beginning of the Government of National Unity there was unhappiness in the National Party parliamentary caucus and other party structures about the constraints that being in government put on the NP’s stance as opposition.162 The fact that the smaller Democratic Party faced no such inhibitions added to NP worries of being outflanked. Debate about whether the party should stay in the Government of National Unity generated almost continuous speculation that the NP would withdraw. In seeking to manage the situation De Klerk, as leader of the NP, adopted a stance which insisted on the right of minority parties to publicly criticise decisions of government which they had opposed in Cabinet. He also, by his own account, adopted a confrontational stance in Cabinet and cabinet committees in pursuit of National Party policy, often, he said, because his own ministers and deputy ministers did not do so. ‘They did well enough with regard to their own portfolios, but did not fare so well when it came to making a fighting stand against the ANC in opposing decisions which were irreconcilable with National Party Policy’.163

The pressures on De Klerk mounted with his failure to get retrogressive positions written into the final constitution, as well as a challenge from the young Turks of the NP represented by Marthinus van Schalkwyk . Cumulatively these developments eroded de Klerk’s standing and a year later he stepped down from active party politics. (In 1997 Van Schalkwyk succeeded De Klerk as leader of the party, renamed the New National Party (NNP) when it withdrew from the GNU, and then joined the ANC in 2005 when the partnership with the Democratic Party in the form of the Democratic Alliance turned sour).

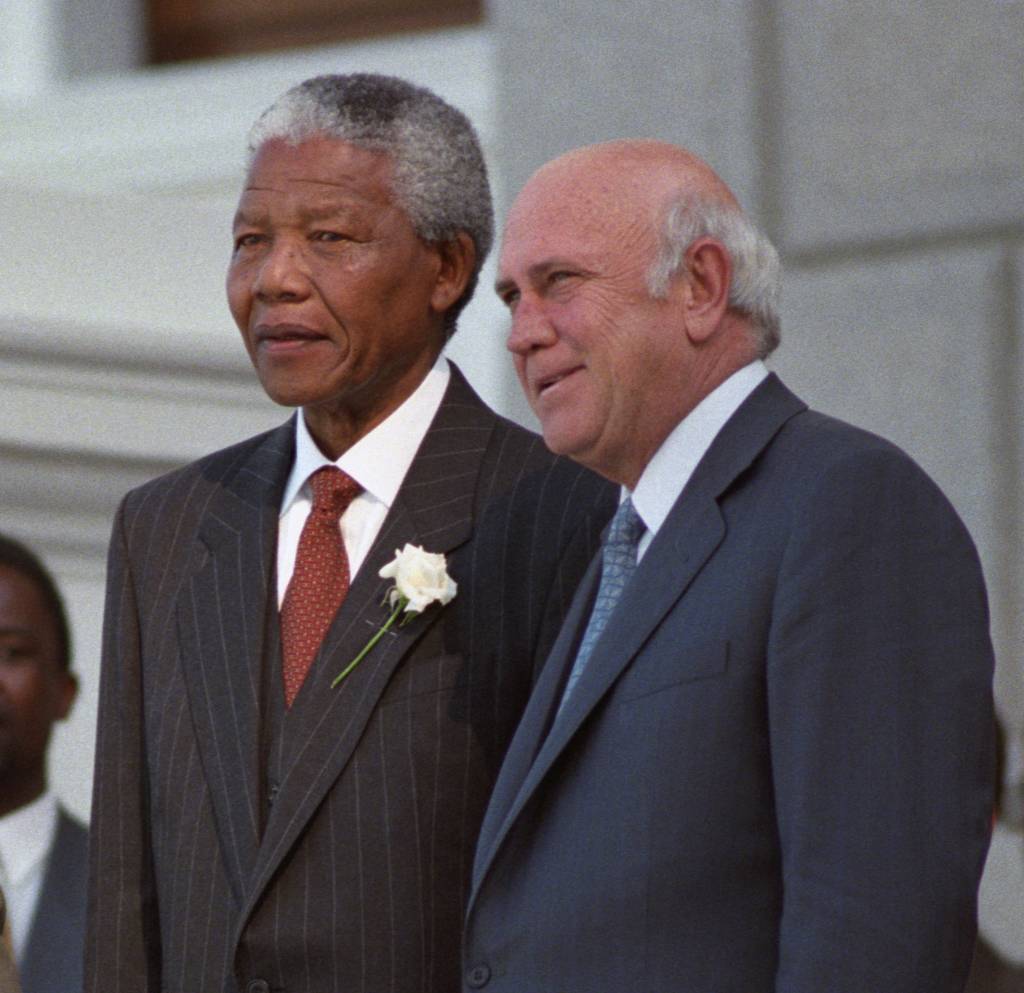

Beyond the party pressures, a legacy of tension and mistrust between De Klerk and Mandela flared especially in relation to issues of violence and security. It had accrued almost from the start of a relationship of leaders between whom there seemed little or no warmth but who – as Mandela frequently said – needed to work with each other in the interests of the country.

The reversal of roles also played a part.

I was in the very unusual position during my Presidency that the central thrust of my policy would inevitably lead to my having to step down as President. I was happy to do this on 10 May 1994 because I felt that I had achieved nearly all the goals that I had set when I started the transformation process. It is, however, never easy to lose power. I did not discuss this with President Mandela. Our relationship within the Government of National Unity was often very tense - possibly because, under any circumstances, it is difficult for the previous chairman of a board to continue to serve on the board of his successor..164

Mandela commented to Tony Leon that ‘De Klerk had not reconciled himself with the loss of power.’165 Although he occupied the position of executive deputy president, Mandela gave him few responsibilities commensurate with what might have been expected of such a position and very far from the powers given to the other (ANC) deputy president. This did not go down well with De Klerk166 as someone who had been a minister and then president in the previous government. It made it still more difficult to convince his party of the correctness of participating in the government.

The most highly charged matters related to peace and security, as they had done during the negotiations. Mandela had insisted that De Klerk either knew of the state involvement – and was therefore complicit – or, as head of state, should have been aware; and in any case should have acted more promptly than he did to counter it when the ANC pointed to state involvement.

When party dynamics and the legacy of mistrust intersected with current issues of violence, crime and security, the repercussions were felt in the Cabinet and in public.

The very first Cabinet meeting on 24 May 1994 had to deal with the matter of the Ingonyama Trust Act to which De Klerk had assented two days before the election, giving the Zulu king administrative power over much of the land in Natal (see chapter 9). To defuse this potentially divisive issue Mandela, who had learnt about the matter from the media the day before, had a ‘candid and harmonious’ meeting with Buthelezi before the Cabinet meeting, which appointed a committee to look into the implications of the Act and make recommendations.167 The Act effectively blocked the application to Natal of the transfer of bantustan land to central government under the new constitution, thereby impeding land reform and other national programmes. Two years later the IFP – faced with the prospect of an adverse Constitutional Court ruling – accepted that national government had the right to amend the act in order to remove obstacles to development.168

The first big clash between Mandela and De Klerk came early on, in January 1995, at a Cabinet discussion on the operation of the Government of National Unity.169 The item had been put on the agenda by De Klerk who wanted to assert the right of the minor parties to act publicly as opposition. The fact that he had recently been publicly criticising the ANC in strong terms set the stage for a sharp debate. Furthermore, Mandela had recently learnt that claims for indemnity regarding offences with a political aim committed before October 1990 had been submitted by 3,500 members of the police force and two cabinet ministers, and granted just before the 1994 election. (The legislation, which didn’t grant amnesty for serious crimes, had also been used by the ANC).170

After ANC ministers had spoken about collective responsibility for Cabinet decisions, Mandela spoke. He attacked De Klerk, citing the indemnity as ‘underhand’ and labelling the NP attitude to the RDP as ‘disloyalty’ to the government. De Klerk left the meeting in anger, saying he and his colleagues would consider their continued participation in the government. The next day, as would happen following clashes to come, the two appeared at a media briefing with a joint statement saying the ‘misunderstanding’ had been cleared up and that ‘We have agreed to make a fresh start which will help us avoid a repetition of the situation which arose earlier this week’.171

A more public incident happened later in the year, at a dinner at the new headquarters of the mining company Gencor at which De Klerk was present. In his speech Mandela commented that the country’s crime problem was inherited from the apartheid government. Realising that he had offended De Klerk, who was also at the dinner, Mandela asked to see him before he left –they met on the pavement outside the building and were soon angrily arguing and gesticulating at each other, unaware of a news photographer whose pictures of the tiff made the front pages of the next day’s newspapers. Again, a press conference assured the country that ‘the hatchet had been buried’172

Other incidents testified to an increasingly difficult relationship between two leaders who, despite coolness and even underlying antagonism, recognized the necessity of working together in the interests of a peaceful transition to democratic government – as Mandela put it on another occasion of rumours of dissension:

‘Whatever quarrels emerge, Mr De Klerk and I understand that we need one another. It’s not a question of personal likes; it’s a question of absolute necessity that we should be together. I think he understands that as equally as I do..173

When De Klerk called for amnesty for General Malan, previously minister of defence in the apartheid government, and other former military officers who were brought to court in relation to a massacre in KwaMakhutha in Natal in 1987, there was another heated public row – among other things, Mandela said De Klerk was ‘becoming a joke’. Again it ended with assurances:

Mr De Klerk is my deputy. It is sufficient what I have said. He is making a valuable contribution in the Government of National Unity and we must not exaggerate it if on occasion we don't see eye to eye. I want to emphasize that this is a man who is playing a very important role in the Government of National Unity. He is supporting my call for national unity and reconciliation.174

There were other occasions, out of public view, on which they didn’t see eye to eye.

On one occasion De Klerk had called the Minister of Heath, Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, to his office and tried to persuade her – unsuccessfully -- on two matters where his constituencies’ interests were at stake: the priority in developing teaching hospitals (he argued for Pretoria against Durban); and health regulations that would affect the tobacco industry. She didn’t tell Mandela about this, but he came indirectly to hear of it and called her in. When she told him that she hadn’t informed him as no decision was required of him, he said, ‘No, you must tell me if he calls you again, but I have told him that he must never call my ministers and tell them what to do.’175

Another was the situation in KwaZulu-Natal. In September 1995, De Klerk wrote to Mandela suggesting that the best way to address the violence in the province would be a meeting between Mandela, Mbeki, De Klerk and Buthelezi to discuss international mediation and political initiatives to lesson tension and violence.176 Mandela’s response sharply exemplified the contours of tension between himself and De Klerk – political, constitutional and personal.

For me he was really a pillar of strength in terms of being able to do the things that were maybe sometimes controversial

The problems in Kwazulu-Natal, and consequently the solutions to those problems, are deeply embedded in the history of the situation that prevails. You, Mr de Klerk, will certainly acknowledge that the present conflict in the province is as much the creation of the policies and strategies of your party and the government of which you were part and presided over, as of any other factors. We need not here entertain the details of that history; we have discussed that previously. It will be seriously misleading, and not helpful for finding a genuine solution, to suggest - as you do in your letter - that the question of international mediation represents one of the fundamental underlying causes to the problems in the province.

I have previously briefed you fully on the discussions I had, as well as the attempts I made to have discussions with Minister Buthelezi on this subject. You are aware that all these initiatives came from me. We would require, as again I have previously told you, concrete suggestions as to exactly what it is you want discussed at the kind of meeting you propose. A futile exercise in meeting merely for the sake of meeting, and making political gestures, aggravates rather than helps resolve the situation.

You are as one of the Executive Deputy Presidents in my government free, and in fact have the obligation, to discuss with me any suggestions you may have about any matters of government policy and direction. It applies in this case as well. What would not be constructive or helpful would be for you offering as the leader of a third party to mediate in what is rather inaccurately being portrayed as simply a conflict between the ANC and the IFP. The historical part played by your party, and the government which it formed, in that conflict totally disqualifies you from performing that role.177

When De Klerk responded writing that he had not being suggesting mediation but a meeting, as a party to the agreement on international mediation, Mandela gave him short shrift: ‘Rather than suggesting pointless meetings, I would appreciate your input on how to deal with the legacy of the inhumane system of apartheid of which you were one of the architects.’178

After De Klerk left government, the relationship took on a different tenor. When De Klerk paid Mandela a courtesy call after announcing his withdrawal, he was, he says, ‘received with warmth and courtesy’.179 Later, when De Klerk announced his retirement from politics, Mandela acknowledged his contribution in an address in the National Council of Provinces .

I should…take advantage of this formal occasion to pay tribute to FW De Klerk who announced his decision to leave active politics a few days ago. Over the past eight years that I have worked with him in various capacities. I was personally impressed by his boldness to acknowledge the march of history, and to take steps that few in his position would dare. The relatively peaceful transition that South Africa underwent was thanks in part to his contribution. In doing so, he put his political career and life in danger, and became one of the eminent midwives of the new democratic order.

We crossed swords with him on many an issue of principle, and he and his party committed many mistakes. But we shall always acknowledge the contribution that he made to the country and its people. I wish him all the best in his new endeavours.180