When the first meeting of the GNU Cabinet, like its predecessors and successors, put the issue of the location of Parliament on its agenda, it had triggered competition with all the paraphernalia and lobbying of PR campaigns. Three years later Mandela, speaking in the National Council of Provinces, felt the need to publicly calm things.

Regarding the question of the seat of parliament, we have been discussing this and I hope all members will appreciate that this is a matter that will be handled with great care. It is a very sensitive matter. The only time I saw members of the ANC in the Western Cape agreeing very fully with the members of the NP was on the question of the seat of Parliament. The Transvalers also speak with one voice on the question, saying that Parliament must be shifted to the Transvaal. Even my name has been involved. When we heard that the Pretoria City Council had said that the President was in favour of Parliament shifting to the Transvaal, I instructed my director-general to write to them to say that I had expressed no opinion on this question.229

An aspect of the compromise that enabled the formation of the Union of South Africa in 1910 as a white-minority state, was the designation of multiple capitals: the administrative capital in Pretoria, in the Transvaal; the judicial capital in Bloemfontein, in the Free State; and the legislative capital in Cape Town, in the Cape Province. Natal, whose capital was in Pietermaritzburg, received financial compensation for the loss of revenue that would result from union.

The arguments about the location of Parliament revolved mainly around costs and economic impact of changing what had been agreed in 1910. What did it cost to have officials regularly travelling between the two capitals; what would it cost to change the arrangement; what would the economic impact be on the capitals. The financial impact of a bigger democratic parliament and its longer sessions became part of the argument, as did the proposition that moving inland would make Parliament more accessible to the public and more exposed to public sentiment.

Cabinet appointed a cross-party subcommittee (headed initially by the minister of transport, Mac Maharaj and later by the minister of public works, Jeff Radebe ) to look into the matter and make recommendations. The ANC NEC appointed a task team to do the same.

While the Cabinet and ANC task teams were processing the issue, intense city campaigns got underway. Political parties were divided and some ministers and ANC members were caught up in the crossfire at a time when protocol required public neutrality on their part. Although Mandela had his own view, given the way the issue was setting cities and provinces against each other, it was necessary for the ANC-led government to present a neutral stance. Among other things, a letter was sent to the mayor of Pretoria (later renamed as Tshwane):

You are quoted as saying that the President and certain ministers support Pretoria in its bid to be the seat of Parliament. The President wishes to make it clear that he has no preference regarding the location of Parliament. President Mandela has also made it clear to all Ministers in government that none of them should be associated with any of the bids …Cabinet has set in motion a process through which the government and parliament shall be provided with the necessary information required for a sensible decision. The question should not be handled in a manner that sets provinces and cities against one another. The President’s preferred route is that a mechanism should be found to ensure that all South Africans, irrespective of their province, rationally exchange views of this sensitive matter, with the aim of reaching consensus.230

Privately, though, Mandela was of the strong view that there should be one capital and it should be Pretoria. To his chagrin, the cat had been let out of the bag in the strangest of circumstances. During a visit by British Prince Edward in September 1994 Mandela was conversing with the prince behind the official residence, Mahlambandlopfu unaware that they were within earshot of the media. Proudly and confidently, he pointed out to Prince Edward the site behind the ridge on which Mahlambandlopfu stood, where he said the new parliament would be located. It was a big scoop for an eavesdropping journalist and the president’s office had to scamper the following week putting out fires within the ANC and across society.

A year before, Mandela had raised the sensitivity of the matter at an ANC caucus meeting, firmly but gently. He addressed the caucus in a solemn manner, pointing out that there were strong emotions at play and that the issue should be handled with care. Then he confessed that he himself had a strong personal view: there should be one capital, ‘and it should be in Qunu!’231

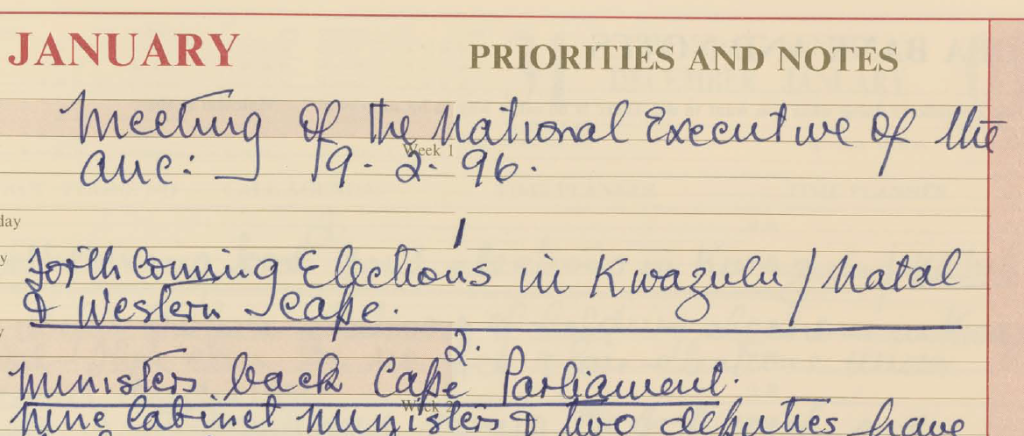

But with ministers he was rougher. His notes for remarks at an ANC NEC meeting on 19 February 1996, gave notice.

‘On the question of the seat of Parliament, I have a very strong view.’

Nine Cabinet ministers and two deputies have broken protocol to sign a public message to President Nelson Mandela supporting the retention of Cape Town as the seat of parliament.

Their message contained in an advertisement in the Argus today, is viewed as a major political coup for the campaign to keep Parliament in the Cape.

The advertisement is also viewed as a sturdy counterpunch to the one contained in the South African Airways magazine Flying Springbok, featuring a multi-personality President Mandela promoting Pretoria as a touring attraction. …

ANC cabinet ministers must explain their actions at the earliest possible convenience.

A process has been set by the government in this regard.232

When Mandela recounted the incident two years later in the Senate, he leavened it with some humour.

The names of the very Cabinet Ministers who had taken a decision that we must have no opinion whatsoever until this procedure had been complied with and the reports have come back to us, I now saw on a list which was circulating in the Western Cape, saying ‘Let Parliament remain where it is.’ I called them and said I wanted an explanation. We have taken a decision here that we must not express any opinion on this matter. They said: No, we saw the names of members of the Cabinet of the NP on a list, and we were thinking, in terms of local government elections, that if we did not join ... I then called Deputy President De Klerk and said: You know the decision. Your Ministers have now gone public and signed a petition that Parliament should remain in Cape Town.

He called his Cabinet Ministers together, and they said: No, we saw the names of Cabinet Ministers of the ANC on a list, and we decided also to join. So I warned both parties that the strongest disciplinary action would be taken against them if they again came out in public and expressed an opinion on the matter. That is the government’s position on this matter.233

I can tell hon members that if I were to make a decision, I am a Kapenaar- I have spent 27 years here

But the six ANC ministers, who had been interviewed by a group lobbying to keep Parliament in Cape Town and quoted in a campaign newspaper advertisement, experienced a bruising meeting with the president at the Tuynhuys.

Madiba basically said to me, ‘So Trevor, you belong to a faction in Cabinet. Your faction is lobbying through the press to have Parliament in Cape Town. You know our views on the matter. You know that I think that the best option that we have to move Parliament to Pretoria is during the one term that I am president. You know that. You know that I’ve asked Mac and Jeff to undertake the research. You know all of that, yet you ignore that and become part of this faction to lobby against decisions that are in the national interest of this country.’

I tried to protest: I wasn’t part of a faction, we had never met on this issue. He said, ‘I’m not interested in your views, you are part of a faction. I want you to hear me: you are part of a faction along with all of you chaps who live here in Cape Town.’ He continued, ‘You know you’re a very good minister and you will become better but if you don’t want to be part of the collective then you must leave. How do you want to conduct yourself?’

I think that for me it was a signal experience because heads of state don’t talk to people; we don’t have that experience in this country. This was Madiba. He had a viewpoint. You could disagree with his viewpoint but he was the head of state and if you didn’t want to be part of the team you had to decide how you played it. For me that was one of the big take-outs of that engagement. It removes the idea of this uninvolved saint who had no views of his own. He was okay with confronting people with issues, even when they weren’t comfortable.234

Another thing that happened about this time, around April or May of 1995, concerned the location of Parliament

The ANC task team reported in July 1997 to the NEC, which took the view that the team needed to do more work.235 The National Working Committee in December 1997 referred the matter to be processed by the NEC about to be elected at its forthcoming conference.236 By the end of Mandela’s term the matter had fallen off the Cabinet agenda – to be raised yet again with a new administration.