With hindsight, the chances of the National Party staying in the GNU for the full five years were not that good from the start. Just prior to the transition, De Klerk had persuaded a divided NP cabinet to accept what he had agreed with Mandela about decision-making in the Government of National Unity. By the time of the election the NP cabinet was even more divided.209 Then the 1994 election results fell short of what the party had allowed itself to expect,210 reducing the number of ministers it would be entitled to and therefore the influence it could have in government.

If pressures on De Klerk as leader of a restive party had repercussions in Cabinet, conversely, developments in the Cabinet impacted on the National Party in ways that strengthened the hand of those who didn't like their party being in an ANC-dominated government. A succession of developments after the election deepened NP worries: the allocation of Cabinet positions; the allocation of chairs of parliamentary portfolio committees where the spirit of GNU principles were not implemented; and Democratic Party’s the uninhibited opposition in Parliament, mostly in defence of white privilege, making the National Party’s muted opposition all the more conspicuous.211

The clash between De Klerk and Mandela over amnesty in January 1995, seemed to confirm the worst to those opposed to participation. It destabilised the party's Federal Congress in February – instead of developing a policy platform to broaden its electoral support, the congress was dominated by argument over whether to stay in government or pull out. NP influence on government decision-making was seen at worst as negligible and at best invisible to the public.212

The fears that being in government would erode support for the National Party213 seemed to be confirmed by the results of the municipal elections held in November 1995 everywhere except Kwazulu-Natal and in some Western Cape rural areas and Cape Town. National Party support fell significantly compared with both the 1994 election results in every province bar two (Northern and Eastern Transvaal as they were then called before being renamed as Mpumalanga and Limpopo ). Compared with the national election results, the drop ranged from five percentage points in Gauteng (one point compared with the provincial election), nine in the Northern Cape (eight compared with the provincial ballot). In the Western Cape – taking in account also that elections in many localities were postponed until 1996 -the drop was seven points (five compared with the provincial election).

The adoption of the draft of the final constitution in May 1996 provided the occasion and the ostensible reason for De Klerk to take the NP out of the GNU. The ANC had made clear that the Government of National Unity was a transitional arrangement that would not be extended beyond the first five-year term. But De Klerk had continued to push for some formal permanent multi – party device in the constitution. Failure to achieve this was cited as the reason for withdrawing from the GNU three years before the agreed five years. At the same time he had come to the conclusion that the GNU itself did not provide for NP influence:

The GNU worked well to start with – but it soon became clear that it was a sham as far as any real power-sharing was concerned. The ANC refused to conclude a coalition agreement with us – and preferred to keep us in a gilded cage – where NP ministers had all the trappings of power – but none of the substance.214

When the Constitutional Assembly voted on the constitution, the NP supported its adoption, but De Klerk gave notice that the NP’s federal council would meet the following week to consider the party’s position in the GNU. Intense media response to this statement prompted De Klerk to call an urgent meeting of the party’s federal executive committee, the next morning.

There was a dinner that evening to celebrate the adoption of the constitution. De Klerk left the dinner early and Thabo Mbeki - who had learnt from a journalist of the planned NP meeting, and that most of those present would be arguing for withdrawal on electoral grounds - left with him in order to try to persuade him not to withdraw, but to no avail. ‘They opted to pull out to keep the party support together.’215

De Klerk’s decision the next day to leave the GNU divided his cabinet colleagues. Two of them, as noted earlier, immediately announced their retirement from party politics, and a third followed suit a year later.

As it turned out, except for the brief interlude of the Cape Town Metro elections216 shortly after the NP withdrawal, the electoral decline of the NP continued, with its leading figures going to various parties and the bulk of its grassroots structures and support taking their allegiance to the Democratic Alliance.

When De Klerk decided to take the National Party out of the GNU, he tried to persuade Buthelezi to leave too. But Buthelezi stayed, not simply because the constitution provided for it. In part, he was mindful of the consequences. ‘A lot of our people had died, more than 20,000 people died. For us as black people it was more important to seek reconciliation than risk escalation of violence.’217 The ANC let Buthelezi know that it would like to see the IFP remain in the government for the full-term.218

For Mandela the withdrawal of the NP from the GNU brought both immediate practicalities and issues of a more strategic nature.

Chief amongst the practicalities was the replacement of the NP ministers. Pallo Jordan came back in environmental affairs and tourism and ANC deputy ministers took over other portfolios of the departing NP ministers.

Of immediate strategic importance was the need to reassure the country, and the international community, that the development would neither threaten stability nor deflect the transition.

Deputy-President FW de Klerk informed me earlier today that the National Party had decided to withdraw from the Government of National Unity. As you are aware, the leadership of the National Party has emphasised that their withdrawal is not an expression of lack of confidence in our multi-party democracy, the rules of which are contained in the constitution which we together adopted yesterday.

On the contrary, it reflects the fact that the National Party recognises that our young democracy has come of age, and would need a vigorous opposition unfettered by its participation in the Executive. We respect their judgment on this matter; as well as the party political considerations which precipitated their decision.

As I emphasised yesterday after the adoption of the new constitution, unity and reconciliation within our society depend not so much on enforced coalitions among parties. They are indelibly written in the hearts of the overwhelming majority of South Africa's people. This is a course that the government and the ANC have chosen to pursue in the interest of our country. It is a course that we will pursue with even more vigour in the coming months and years.

The policies that the Government of National Unity has been executing are premised on the needs and aspirations of all the country's people. This applies to all areas of endeavour, underpinned by the Reconstruction and Development Programme, to improve the quality of life of the people through sound economic policies of fiscal rectitude and other measures to promote growth and development.

These policies will not change. Instead they will be promoted with even more focus.

Though the Imperative of Government of National Unity was written into the interim constitution, the onus was on parties which attained more the 10% of the vote in April 1994, voluntarily to decide whether or not to take positions in cabinet.

As the majority party, the ANC welcomed the fact that the NP and IFP decided to take part in the Executive, especially in the early days of our delicate transition.

I wish to thank Deputy President FW de Klerk and his colleagues for the constructive role that they have played. I am confident that we shall continue to work together in pursuit of the country's Interests, and that their withdrawal will have the effect of strengthening, rather than weakening, their commitment to the country's political, security and economic interests.

Indeed, we are firmly of the view that the National Party has a continuing responsibility to contribute to the process of eradicating the legacy of apartheid which they created. As such, we hope that their decision to play a more active role as an opposition party, does not mean obstructing the process of transformation or defending apartheid privilege.

Mandela also went out of his way, as noted in a previous chapter, to acknowledge those leading NP figures who had contributed to the work of the GNU and the transition in ways that transcended their party membership, to the extent that they no longer felt at home in the party and had withdrawn from party politics. A common thread in their later explanations of their decision was a conviction that the NP did not have the capacity to change in ways it would have to if it was to play a significant role in the democratic era.

For the ANC too, the NP withdrawal brought strategic questions both of a party political nature and to do with the transformation of the executive and the state (dealt with more fully later, in The ANC and the transition).

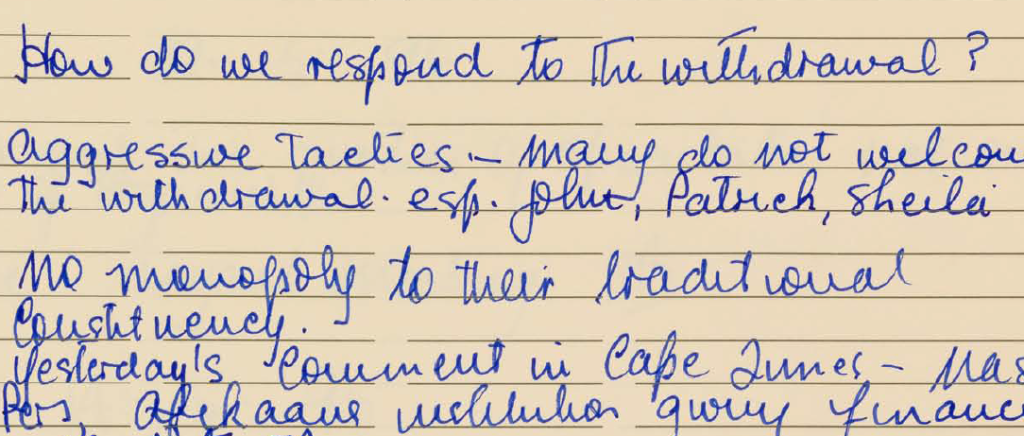

At the NEC meeting in May Mandela noted the party political implications, seeing both challenge – expectation of a vigorous campaign in the approaching Cape Town municipal election – and, noting division in the NP over the withdrawal, opportunity for the ANC to do more to make inroads into the Coloured and Indian communities – parties he noted ‘had no monopoly on their traditional constituencies’.220

At the August NEC meeting he expanded on a broader issue and its implications for managing the transition and national unity:

With the withdrawal of the NP from government, the question of the future of multi-party government has arisen sharply:

Firstly, we need to examine our relationship with the IFP, both in the context of its participation in the GNU and the political developments in KwaZulu-Natal. What is the best approach required in dealing with this organisation?