Just before leaving office, Mandela hosted a visit by Muammar Gaddafi to South Africa. At a luncheon in Gaddafi’s honour, he looked back.

In many ways, our modest contribution to resolving the Lockerbie issue will remain a highlight of the international aspects of our Presidency. No one can deny that the friendship and trust between South Africa and Libya played a significant part in arriving at this solution.698

There must be a kernel of morality to international behaviour

The obstacles to such an approach in a world dominated by selfish geopolitical and commercial interests showed themselves all too soon after Mandela’s release.

In May 1990 he visited six African countries, amongst them Libya, to give thanks for past support and build support during negotiations. In Libya, he thanked Gaddafi for Libya’s support. And he reacted to the sight of the ruins of Ghaddafi’s residence which had been targeted in a United States bombing of Libya in 1986, ostensibly in retaliation for an act of terrorism for which Libya was alleged to be responsible. ‘Whatever differences there may be between countries and people,’ Mandela said, ‘it is unacceptable that any one attempts to murder an opponent and his family.’699

Though muted compared with what came later, negative reaction in the South African press and in the United States were a foretaste of what was to happen over the next decade as he helped resolve international tensions over sanctions on Libya and the issue of Lockerbie (the bombing of the Pan American passenger plane over Lockerbie in Scotland in 1998, with 270 fatalities including passengers, crew and Lockerbie residents.)

By the time Mandela went to Libya again, in 1992, arrest warrants had been issued in Scotland for two Libyans as Lockerbie suspects. Rather than hand the suspects over, Libya had developed an approach to resolving the issues, mobilising support in regional organisations, in particular the Arab League and the OAU which were concerned as much about Lockerbie as about the United States’ unilateral imposition of sanctions on Libya and their impact on the rest of Africa.700 Mandela briefed the ANC National Executive Committee, of this visit and the statement he wrote and issued just before leaving Tunisia on his way to Libya.

The issue has attracted a lot of attention, especially outside, and this is the statement I Issued in Tunis on the Lockerbie incident:701

‘The ANC has consistently condemned all acts of terrorism. The Lockerbie Disaster was a tragic incident which resulted in the unfortunate loss of innocent lives. The ANC once again takes the opportunity to express deep-felt sympathy to the families of the deceased.

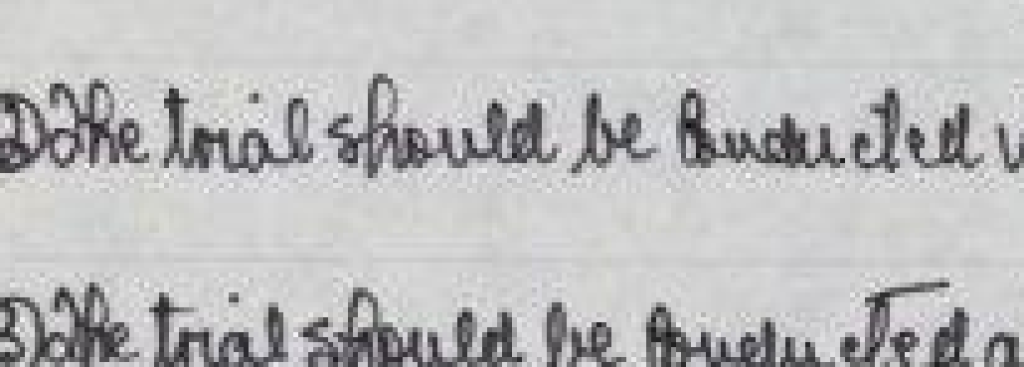

‘It is in the interest of peace, stability and security that if there is clear evidence of the involvement of identified suspects they should be arrested and punished as soon as possible. In the present climate of suspicion and fear it is important that the trial should not be intended to humiliate a head of state. It should not only be fair and just, but must be seen to be fair and just. This must be in the context of respect for the sovereignty of all countries.

‘The ANC believes that if the above objectives are to be achieved, the following options should be considered:

- If no extradition treaty exists between the countries concerned the trial must be conducted in the country where the accused were arrested.

-The trial should be conducted in a neutral country by independent judges

-The trial should be conducted at The Hague by an international court of justice.

‘We urge the countries concerned to show statesmanship and leadership. This will ensure that the decade of the Nineties will be free of confrontation and conflict.

It was issued after consultation with our delegation As you know the US, UK and France are demanding the handing over of two Libyan citizens who are suspected of having been responsible for the Lockerbie disaster.

When I reached Harare I met Mr Shamurariya, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Zimbabwe. He had a message from Mugabe who informed me that the OAU has taken a position on this question along the same lines contained in my statement. They are aware of the culprits in this regard, and these three powers are aware of who is responsible. They first accused Syria, Iran and the PLO. But then when Syria joined the Western powers in the Gulf war, they dropped the charge against these three and accused Libya. They know it is not Libya.

Mandela listed a series of international representatives he had spoken to about his statement: Hank Cohen, US Under-Secretary of State, (who confirmed that the statement was not in conflict with a resolution on Lockerbie due to be adopted by the Security Council later that day); Kofi Annan, the UN secretary general; Lynda Chalker, UK minister of overseas development; and the Spanish and French embassies.

Mandela was not deterred by the negative ‘attention’ which had greeted his visits to Libya and which was sustained over the years to come. His response, affirming the autonomy of South African foreign policy, was exemplified when he accompanied the Norwegian prime minister on a visit to Robben Island in February 1996. He said he would not forget the ANC's friends from the apartheid years.

Both our enemies here [in South Africa] and our friends In the West said to me, 'If you want to be acceptable to the world get rid of Cuba, get rid of Muammar Gadhafi.’

One of the leading heads of state said that to me, when he invited me to his country: He urged me to break with Castro's Cuba and Libya leader Muammar Gaddafi. ...

We will never renounce our friends, no matter how unpopular they may be with [countries in the West].

Your enemies are not our enemies and that is the position even today and that is why I have invited Castro to visit South Africa so that the people of South Africa can thank him directly.

I'm also thinking of inviting Muammar Gaddafi to come to this country, so that we can have the opportunity to thank him . …

Mandela’s involvement in mediating the Lockerbie negotiations began in earnest in 1997,704 by which time the UN Security Council had imposed air travel sanctions on Libya because they had not handed over the suspects. On his way to a Commonwealth Heads of Government meeting in Scotland, Mandela visited Libya, hoping to convince Gaddafi to reach an understanding with the West.705 Before reaching Libya he called for the lifting of sanctions against Libya, a position adopted by the OAU Summit earlier in the year.706

This time Mandela entered Libya from neighbouring Tunisia by car, to avoid violating the UN embargo on air travel to Libya. Addressing the media there, he reiterated his position.

The Organisation of African Unity has called for the suspects to be tried in a neutral country. That is the position which I discussed in 1992 with the Americans, with President Mittterand, with, King Carlos of Spain, as well as Prime Minister Major. Our position is that the suspects must be tried by a neutral country. We cannot accept that one country should be complainant, prosecutor and judge at one and the same time. Justice must not only be done but must also be seen to be done.

He was asked if the angry reaction, especially from the United States government, affected him.

Well, a politician must not have a delicate skin. If you are a politician you must be prepared to suffer for your principles. That is why we chose to remain in prison for twenty seven years because we did not want to change our principles. [Gaddafi] is my friend. He helped us at a time when we were all alone, when those who are now saying we should not come here were helping the enemy. Those who say I should not come here have no morals and I’m not going to join them in their lack of morality.707

And before I discuss it with the press, I want to handle it in such a way

The negotiations in which Mandela was now involved, became a protracted and intensive diplomatic effort involving the combined efforts of Mandela’s envoy, Jakes Gerwel, and the Saudi diplomat Prince Bandar bin Sultan, as well as the United Nations, to achieve a solution involving the three countries and their leaders, Gaddafi, Clinton and Blair. The initiative was bolstered by growing multilateral support in the OAU, Non Aligned Movement and Arab league, and by a ruling of the International Court of Justice that it had jurisdiction over the Lockerbie matter, implying that it was a legal matter rather than a matter of international security for the United Nations to deal with.708

Within this context, Mandela and his envoys created the space publicly for negotiation and movement towards compromise from previously declared positions while using persuasion and sometimes hard words in private. The two envoys brought together Saudi Arabia’s relationship with the United States and South Africa’s with Britain, as well as Gaddafi’s trust. Mandela’s relationships with Gaddafi, Clinton and Blair came into play at crucial moments, exemplifying the role of direct personal relations among leaders in Mandela’s approach to negotiations and conflict-resolution.709

During a meeting with President Clinton in 1998 in South Africa, Mandela asked Clinton’s aides to leave them alone so he could speak privately to Clinton. They were joined without prior notice by Prince Bandar. As they briefed Clinton on the state of Libyan negotiations, according to Jakes Gerwel, ‘We were surprised to find how little Clinton knew about this matter.’ Clinton’s National Security Advisor, ‘almost had a heart attack over having the president talk on something he hadn’t been briefed on before.'710

As he regularly did in negotiations, Mandela did nothing to diminish or embarrass Gaddafi. He built a close personal relation with him, praising and defending him in public, honouring him with South Africa’s highest honour that could be bestowed on citizens of other countries. But in private, when he felt it was necessary, he spoke harshly about the need to speak respectfully of others, such as the United Nations, even if he did not agree with them.711

Finally in 1999, the conditions matured for the intervention to succeed, Opinion in Britain and the United States had also become more favourable. After two years of intensive diplomacy, Ghaddafi agreed to hand over the two suspects; the British government agreed that the trial could be held in a Scottish court in The Hague, and the United States and United Nations agreed to lift sanctions. Mandela announced the breakthrough at Libya’s Congress of the People.

It is with a great deal of sadness that we see, at the end of this century, that the world, and Africa in particular, are still beset by conflicts and situations of war. The strife in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Angola, Ethiopia and Eritrea, Sierra Leone, Somalia and other parts of our continent, undermines our dream of a regenerated Africa. More than that, it cruelly subjects the people of the continent to danger, insecurity and deprivation.

All who call themselves leaders and who have taken it upon themselves to represent the people, must put the people first. Nothing can justify the untold suffering of ordinary children, women and men where leaders chose war and strife rather than the peaceful resolution of conflict.

I am very happy to note my Brother Leader`s resolve, on behalf of the Libyan people, to work for peaceful resolutions of the conflicts on our continent. It provides us with special strength to be able to point to his unswerving support for South Africa`s position that the military option provides no solution to any of these conflicts.

We are grateful to have Libya as our ally in the call for a cease-fire and withdrawal of all foreign forces from the Democratic Republic of the Congo so that the Congolese can themselves find an inclusive political solution.

South Africa regards Libya as an important role-player in the Organisation of African Unity and in the affairs of the continent. Africa`s rebirth requires the energy of this great country and people. The limitations which United Nations sanctions place upon Libya are not only to the detriment and suffering of Libya. They affect the whole continent and beyond.

It is also for that reason that I, together with my brothers The Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques King Fahad and Crown Prince Abdullah, lent our support and assistance in attempts to resolve the Lockerbie issue.

It is with great admiration for the Libyan people that I can today announce to the world that Libya has decided to write to the secretary-general of the United Nations to give a firm date for the handing over for trial in the Netherlands of the Two Libyan nationals named as suspects in the Lockerbie case.

At the outset, we must make a point which one would have assumed in this modern day needed no making. We are speaking of two people suspected of a crime, not of people proven guilty. Too often the impression is given that Libya is harbouring convicted criminals. As a world which believes in justice and which is committed to due legal process we must cling to the principle that people should be presumed innocent until proven guilty.

I wish to take the liberty of referring in some detail … to the text of the letter that the Libyan authorities will be addressing to the Secretary-general. I have the letter in my hand.

I am confident that the secretary-general will understand and pardon me for publicising the contents of a communication to him before he receives it. We do so because the writing of this letter has taken great courage and self-sacrifice on the party of Libya, and because King Fahad, Crown Prince Abdullah and I take responsibility in your presence and before the Libyan people for our part in that decision.

We therefore want you and the world to know that we, the leadership of Saudi Arabia and of South Africa, put our honour before you as guarantee of the good faith that we believe the leadership of the United Kingdom and the United States as well as the Security Council had pledged in this regard.

The letter starts by expressing the Jamahyria`s thanks and appreciation for the efforts of tary-general, myself as President of South Africa, and the those of the Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques King Fahad bin Abdulaziz al Saud and His Royal Highness Crown Prince Abdullah bin Abdulaziz al Saud, to find a just solution to th>span class="MsoHyperlink">e Lockerbie issue, from which Libya has suffered for more than ten years.

The letter then states, and I quote (but I must first state that the Leader had entrusted to me the choice of the precise date):

‘The Jamahyria agrees to ensure that the two suspects would be available for the Secretary General of the United Nations to take custody of them on or before 6th April 1999 for their appearance before the court.’

This, the letter states, is based on the following points which had already been agreed:

- A Scottish court shall be convened in the Netherlands for the purpose of trying the two suspects in accordance with Scottish law and based on the agreement reached between the legal experts of the United Nations and Libya, and with the presence of international observers appointed by the secretary-general of the United Nations. The Jamahyria would wish that this be done also in consultation with the Republic of South Africa and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

- The suspects if convicted will serve their prison sentence in Scotland under UN supervision and with assured access to a Libyan Consulate to be established in Scotland in accordance with the arrangements reached with the British government.

- The sanctions imposed on the Jamahyria will be frozen immediately upon the arrival of the two suspects in the Netherlands. Thereafter the sanctions will be lifted upon submission, within 90 days, of a report by the secretary-general to the Security Council stating that the Jamahyria has complied with the Security Council`s resolutions.

The Jamahyria, in this letter, also seeks to bring again to the attention of the secretary-general, the following points:

- The Jamahyria, as it has stated before on numerous occasions, opposes all forms of terrorism and condemns all acts of such heinous criminality. The Jamahyria recalls that it has itself been a victim of terrorist acts which could not be condoned by any religious, human or international laws.

- The Jamahyria pledges co-operation with the investigation, the procedures and the trial, within the framework of Libyan laws and legislation.

- The Jamahyria reiterates what it had previously declared regarding compensation in the event of the two suspects being found guilty by the court and a final verdict being reached.

In the light of all the above, the Jamahyria states its view in the letter that the Security Council should pass a resolution with regard to this arrangement in a form binding on all concerned parties.

That is the essence of what is in the letter.

King Fahad, Prince Abdullah and I believe that, with those undertakings, Libya has taken the issue that has beset us for so long, to a new phase. The Libyan people can rightly claim that they have made major concessions, putting aside understandable considerations of national sovereignty for the betterment of international relations and for a world of greater normality.

We have no doubt that all other parties will respond with equal magnanimity to this development so that the issue can be resolved speedily. We are particularly hopeful that these undertakings will put the secretary-general in a position to expedite his report to the Security Council to have sanctions against Libya finally and fully lifted. We hope that all members of the Security Council including Permanent Members will redouble their commitment to restore normality to international relations.

I know that the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia quite recently upgraded their diplomatic presence in Tripoli from the level of charge d`affaires to full ambassador. That is a sign of Saudi Arabia`s commitment to their partnership with Libya.

I am honoured and privileged to announce that South Africa will be establishing a resident mission in Tripoli soon. When I arrive back in South Africa tomorrow the implementation of that decision will be one of the first matters that I shall attend to.

This is something we would have done at some time or other in any case, as Libya has been such an important ally for so long. That we do so now is also intended to signal to the Libyan people and the world that we are proud of the steps that Libyan people have taken today in regard to the Lockerbie issue. It indicates that South Africa will continue, together with our Saudi friends, to champion their cause in this matter.

I must now take leave of you for the last time in my official capacity. This morning, more than ever before, I take my leave with great happiness and pride in the people of my continent.

Not long after that, Mandela honoured the two envoys, Jakes Gerwel and Prince Bandar, taking the opportunity to reflect on the significance of the successful resolution of a source of international tension

Not only are we honouring rare and exceptional achievement by two accomplished individuals.

We are also celebrating the vindication of an approach to solving problems that is based on the common humanity of all people everywhere. We take joy in the strengthening of our hopes that the peaceful resolution of conflict can become the normal approach.

We are also, thankfully, recording an event that confirms the efficacy and enhances the authority of the United Nations as the world body responsible for collective action in pursuit of world peace.

These may sound large claims to be making, especially if they appear to be the achievements merely of two individuals.

There is no doubt that but for the efforts and the qualities of the two persons we are honouring as best we can, we would not today be in a situation in which two Libyan men would be awaiting trial in a Scottish Court in the Netherlands, with the hope of a fair hearing; in which the families of victims of the Lockerbie disaster could take some comfort from the fact that the judicial process is under way; and in which the Libyan people would be freed from the suffering inflicted on them by years of sanctions and the insecurity engendered by the memory of armed attack on their capital.

It is right that we should honour the two envoys. Their exceptional achievement required an exceptional combination of skills and virtues: discretion; modesty; patience; a commitment to justice; and an intellectual and moral depth that both extends trust and engenders it in a situation marked by years of conflict and tension.

But we also know that what they did was made difficult but at the same time possible by the international environment within which they worked. That environment is defined on the one hand by institutions and norms that promote justice and peace, and on the other by entrenched and long-standing divisions.

If we praise their discretion, it is in the knowledge that this was an issue engaging the most powerful interests and bringing into play emotions and attitudes that have been divisively deployed in world affairs. Intense international media attention constantly solicited them to occupy a public place on the world stage. ‘Lockerbie ‘and ‘Libya’ had become landmarks in the media landscape of a world divided between good and evil, the reasonable and the irrational, saints and demons.

Indeed should we not as an international community ... step back, in the wake of the resolution of the Lockerbie issue, to ask ourselves how well we, and the means of communication which we have created, are serving world peace in the portrayal of others, in particular religions of the world different to those we may share in!

Should we perhaps ask whether the portrayal in much of the world's media of Islam in particular may not be assisting in the creation of new generic divides in the post-Cold War world?

As we witness the inhuman acts of ethnic cleansing in Yugoslavia, we may be reminded of how the way we speak about one another can influence behaviour. And as we watch the destructive bombing of the capital of a sovereign country, may we not ask whether the communications media are not now lending themselves to the prolongation of a conflict whose resolution should urgently be sought in negotiations and through the United Nations?

We inhibit the peaceful and negotiated resolution of conflicts not only by the extent to which we demonise one another. We do so also by the degree to which we separate on the one hand the processes of politics and international affairs and on the other hand, the moral relations between ourselves as human beings.

Our envoys succeeded because they acted upon certain fundamental moral premises: that men and women must be presumed to be of good intention unless proven otherwise; that there is in all of us a common humanity guided by the same fears and hopes, the same sensibilities and aspirations. That being so, talking to one another and discussion must be the prelude to the resolution of conflicts.

South Africa and her people suffered for generations because those with power refused to talk on this basis to those who they oppressed.

When we dehumanise and demonise our opponents we abandon the possibility of peacefully resolving our differences, and seek to justify violence against them.

In the achievement of our two envoys, African and Arab, is embodied also the fact that peoples who were prevented by superior force from determining their own destiny, have reclaimed that dignity, and are once again exerting a profound influence upon world affairs and the course of human history. It is a significant contribution to the Renaissance of the inter-linked African continent and Arab world.

In particular it accords with the perceptive of those who, having achieved their liberation with the collective support of others, are all the firmer in their conviction that the challenges facing the world require collective solutions and a consistently multilateral approach. What we are recognising today includes that fact that what was done, was done in loyal and disciplined service of the United Nations Secretary-General.

As we honour two individuals for their accomplishment, we also acknowledge three heads of state or government who were prepared to take that extra step to resolve a matter that has occupied the world for far too long, even though the common sense of compromise was always clearly available.

Current developments on our continent and elsewhere in the world may often seem discouraging. But the actions of these statesmen in this matter signal the hope that the leaders who take us into the next millennium will be men and women who put the well-being of humankind in its entirety above sectarian and narrow national considerations.

It was not quite the end of the matter. It was only closed in 2003, after one suspect was found guilty in 2001 (in a judgment which left some, including Mandela, unconvinced of its fairness). The United Nations sanctions, which had been suspended in 1999, were lifted in 2003, after agreement was reached on Libyan compensation to the families of those who died in the Lockerbie incident and a similar incident involving a UTA airline plane in Nigeria.

But the process itself, and subsequent events, underlined the fact that such negotiations, informed in part by contradictory expectations among the protagonists and in part by public posturing, can be messy. Indeed, Mandela himself was not entirely satisfied with the outcome.

I held discussions with Prime Minister Major of Britain and President, firstly President George Bush Senior, negotiating about the delivery of the suspects – a problem which took eight years before we could resolve it and after we had got certain guarantees, one of the most important being that if Libya delivered the suspects the sanctions would be lifted, not suspended, lifted.

We eventually succeeded in persuading President Gaddafi to deliver the suspects and we expected, therefore that the West would honour its undertaking. Unfortunately that was not done because they merely suspended [sanctions].

Now we also agreed that if the suspects are convicted they will be put in a jail which is controlled not just only by Scotland, by the United Nations as well and that they will not be visited by anybody without the express consent of the Libyan government.

I hope that the West is going to honour that undertaking. Now I see in some of the media that already there is a feeling that the West is shifting its goalposts because they made it clear, that those sanctions were intended to get Libya to deliver those suspects. They delivered the suspects but nevertheless some countries are saying we are not going to suspend sanctions. That is moving the goal posts. When the head of state of a country makes a statement on international affairs we expect their successors to honour those agreements. Because once those agreements are dishonoured you are introducing chaos in international affairs.

I trust President Gaddafi without reservations. I have been dealing with him from the time I came out of jail in 1990. Our organisations have been dealing with him whilst I was in jail. He has trained many people where he was condemned by the West for training terrorists. Those so-called terrorists are now heads of state and the West is now dealing with them. They have forgotten that they regarded these people as terrorists.

In approaching negotiations and resolution of conflict, Mandela emphasised confidentiality, not out of a liking for secrecy but because of a strong conviction that parties to negotiation need space to shift, to consult with their organisations, to compromise with dignity or at least without humiliation.

When delegates at the ANC’s national consultative conference in December 1990 demanded that the leadership should not engage in confidential discussions with the government and National Party, Mandela reacted sharply – that statement, he said, could only be made by those who do not understand the nature of negotiations.

Linked to that was his treating those in negotiation with public respect, whether they were political adversaries or heads of state.

But politically he knew also that these are leaders, these are heads of state, whether he likes it or not, it is not up to him to choose them, the Abacha’s and others. They are presidents of the country, and when you diminish a head of state you diminish the people they represent. It’s not personal, it is what is called statesmanship. If you diminish a head of state, literally you are also diminishing the people he represents. That’s why he might be very harsh privately, but publicly he would try to keep a certain level of respect and dignity to the leaders.715

Trust was the crucial element and Mandela entered negotiation and efforts to resolve conflict presuming the integrity of those involved. It was when that trust was violated publicly that his anger would flare.

The combination of confidentiality and public respect for interlocutors if anything, heightened the difference between what the public saw when Mandela acted to resolve conflict, and what happened behind closed doors. As much as it kept the substance of the Lockerbie negotiations largely out of public sight until years later and left observers to fill gaps with speculation, it also coloured perceptions of other contributions to the search for world peace. As in the case of Libya, it created space for observers to guess or impute motives and to entertain the belief that the principles for which democratic South Africa stood were compromised or its interests jeopardised by interventions in other areas, such as Indonesia and East Timor; Morocco and Polisario, Sudan and China.