But if Mandela focused continually on development as he conveyed South Africa’s foreign policy, his most intense engagement was in contributing to humanity’s search for peace and democracy. That drew him into some fraught situations whose ambiguities brought as much criticism as praise. The results highlighted the strengths and the limits of both collective action and individual initiative.

Nigeria perhaps posed the biggest challenge. Nigeria’s support for the liberation struggle was far-reaching: financial contributions, military training, and support of exiles and refugees. That history made developments during Mandela’s presidency especially difficult and emotional, compounded by the fact that the OAU was not always fully in agreement with his approach to resolving the problems.

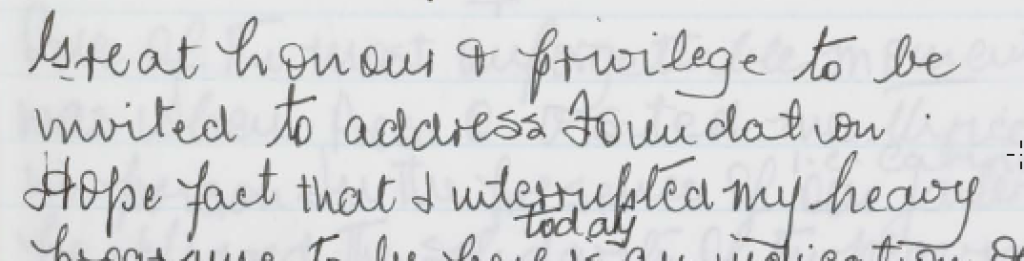

During the closing days of Mandela’s presidency, the transition from military to civilian rule was completed when General Obasanjo took office after winning an election, taking over from General Abubakar who had overseen the transition following the death of Sani Abacha. Obasanjo had himself been a military ruler until he handed over to an elected president in 1979. In 2000, he invited Mandela to Nigeria for the launch of a charitable foundation honouring of General Shewu Yar-Adua who had died in prison after being arrested with General Obasanjo for allegedly plotting a coup against Abacha. Mandela’s draft of a speech for the occasion ranged across five decades, from the early 1960s – when he visited Nigeria seeking support for the ANC, and lived there for some months with a minister who kept him in hiding from South African agents – to the recent developments.

I first visited Nigeria about 40 years ago when Dr Azikiwe was Governor General and Mr Balewa Prime Minister. The solid support I received from all sections of its population was a tremendous source of inspiration.

But there is a real danger of being lyrical when dealing with President Obasanjo. We watched his actions and comments from jail as he moved around Africa, including our region, pledging his support to liberation movements and human rights organisations.

One of the most unforgettable moments was when President Obasanjo visited me thrice in prison [as a member of the Commonwealth Eminent Persons Group]. In the presence of our jailers – that is cabinet members – he pledged the solidarity of the Nigerian people with our struggle and made it clear that the democratic world could not tolerate any form of discrimination and exploitation.

It is very rare in history for a strong and popular leader to surrender power. One of the striking features of President Obasanjo is that he did exactly that and transferred power to civilian authority. He is in the same league as the late Nyerere of Tanzania and former President Quett Masire of Botswana. They stepped down at the height of their power and popularity.

As he looked back over Nigeria’s recent political history Mandela was silent about his engagement with the military ruler who had preceded General Abubakar. General Sani Abacha seized power in 1993 from a transitional government that was in the process of reinstating civilian governance after eight years of military rule. He instituted a brutal dictatorship. Soon after Mandela became president of South Africa, Nigerian opposition politicians and civic groups pressed him to intercede on behalf of imprisoned political leaders and activists and to mount pressure for a return to democracy.

Mandela engaged directly with Abacha during a visit to Nigeria in November 1994, when he raised the matter of the imprisonment of Moshood Abiola who was presumed to have won the presidential election in 1993. Deputy-President Mbeki went to Nigeria as an envoy in July 1995 and was given a commitment by Abacha that Ken Saro-Wiwa and eight other environmental activists would not be executed and that Generals Obasanjo and Yar’Adua, arrested on suspicion of involvement in a planned coup, would be released.687

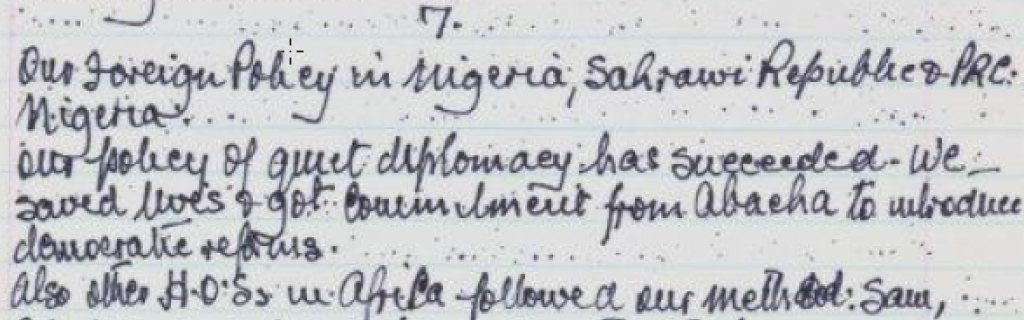

Rather than denounce Abacha publicly as he was urged to do, Mandela continued to engage privately, pursuing his belief that negotiation and persuasion could succeed. ‘Our policy of quiet diplomacy succeeded,’ he told the ANC NEC in December 1995. ‘We saved lives and got commitment from Abacha to introduce democratic reforms.’688 Indeed death sentences on some prisoners were lifted, but the assurance that Ken Saro Wiwa and his fellow activists would not be executed was dishonoured. While Mandela was at the November 1995 meeting of Commonwealth Heads of Government in New Zealand, news was received that they had been executed. Mandela, hurt and angered by this betrayal of his trust, took action beyond the norms of diplomacy.689

His fury, for such it was, derived not only from his passion for all of Africa – especially its largest nation – to chart a new path towards democracy and development, and a sense of awkwardness when the opposite was the case. There was also a personal attribute that came into play, namely the value that he placed on the personal integrity of people with whom he interacted: when that was betrayed, his anger, often unrestrained, would came to the surface. De Klerk during the Codesa negotiations; and Kabila during the Zaire/DRC peace process had experienced the brunt of such moments of unbridled anger.

There was in Madiba a very genuine transformation which had occurred in him from a very angry person to a more serene and balanced and forgiving person. There were moments when that angry person he used to be when he was much younger would come out because it was part of his personality and this is when if he is in public and gets angry you would feel that I better not be on the opposite side. He had managed with such discipline to transform himself, but there were moments in which these things, those elements of anger, would escape the disciplined person that he had become and then they would come out.690

not only had [the messages] been ignored but he had deceived him.

Further, as noted above, Mandela had developed close personal relations with General Obasanjo, who had also been imprisoned by Abacha. This applied, too, to Moshood Abiola, a politician and business magnate whom he had met a number of times during South Africa’s negotiations and who, besides affording financial support to the ANC, provided wise counsel to Mandela on how to manage various complex issues in that period.

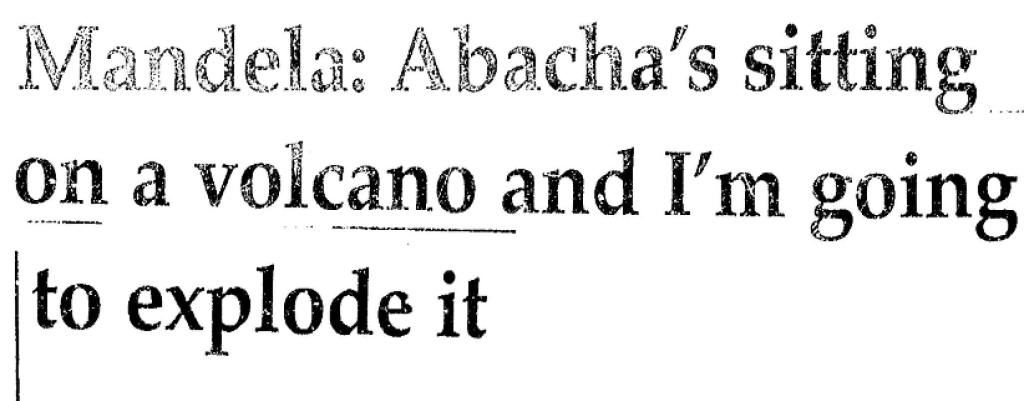

Mandela called publicly for the immediate suspension of Nigeria from the Commonwealth and the imposition of sanctions. In the days that followed he angrily demanded and threatened strong action. Speaking to a journalist not long after the Commonwealth meeting, he declared, ‘Abacha is sitting on a volcano. And I am going to explode it under him.’ South Africa’s decision, he said, to approach the Nigerian authorities in the days before the executions ‘sensitively, to persuade them not to take irrational decisions’ had been vindicated by the lives that been saved. But, after the executions, he said:

I felt we were dealing with an insensitive, frightened dictator, and in my view, we should use the strongest method to show our disgust and resentment of what he had done.

What we are now proposing are short and sharp measures which will produce the results Nigerians and the world desire. We are dealing with an illegitimate, barbaric, arrogant, military dictatorship which has murdered activists, using a kangaroo court and using false evidence.

Speaking of his attempts to get other heads of state and the Shell petroleum company to support his call for sanctions, he said:

My first attempt with Prime Minister Major was not as effective as it could be. I am going to continue talking to Clinton, Major and Jiang Zemin, and other leaders. I am determined to do so because I believe that very firm action should be taken against Nigeria. ...

But the Commonwealth had not adopted the call for sanctions. What it did do was suspend Nigeria’s membership and set conditions, to be implemented within two years, for the country’s return. They included the immediate release of General Obasanjo, Abiola and their colleagues, and visible signs of democratisation. A Commonwealth Monitoring Action Group of eight countries was established to see that the conditions were observed.

Nor did other countries support the call for sanctions. In time, rather than risk isolation, South Africa gradually aligned its stance with the positions of the multilateral forums of international diplomacy. Thabo Mbeki, who had a good understanding of Nigerian politics, having spent years there, was given the task of dealing with the fall-out. The OAU Secretary-General also spoke to the Nigerian government to explain South Africa’s position.

Mandela outlined the cooler approach after a visit to South Africa by the Commonwealth Secretary-General and then a Special Summit of SADC on Nigeria attended also by the OAU Secretary-General, at which the question of sanctions was not on the agenda.

We [the Commonwealth Heads of Government] set up a monitoring group of eight to handle the question of Nigeria and the initiative now on this question remains with that group and any ideas that we had, have now to be channelled through that group. We are keen to respect a structure which we, ourselves, were parties to setting up. And it would not be desirable for us now, in our individual capacities, to make policy statements in regard to Nigeria. ...

Since our initial positions, there have been developments – communication to us by the Secretary General of the United Nations, the report by the Secretary General of the OAU, the appeal by President Lansana Conte of Guinea-Conakry. We are a committee that wants to operate within the context of the entire world and for that reason we have refrained from taking any individual views. And of course as SADC we have a point of view but that point of view must be channelled through this committee of eight.

We are giving the monitoring group of eight the opportunity to formulate an initiative on this question. We have mentioned in our discussions here that that group must have been considering what is the next step to move the process forward. They have now developed a skill, an expertise and it is absolutely necessary for us to give that group the opportunity to take the first step forward. ...

In briefing me on the discussions that he has had with General Abacha the [OAU] Secretary General has expressed confidence that he was able to move the Abacha regime to take visible steps in normalising the situation in the country and in ensuring that at least with regard to the large group of people who have been arrested, there is hope on his part that they may be released soon. And we think that is a positive development which we should welcome. ...

Well, as President Masire has pointed out, we set up a monitoring group of eight to handle the question of Nigeria

He stressed, in a media interview after his meeting with the Commonwealth Secretary-General, that action was against the regime, not the people of Nigeria.

We are making a clear distinction between the Abacha regime and the people of Nigeria. The people of Nigeria want democracy to be restored in their country and we are fully in support of that. We are working with them and our aim is against the military government especially for its insensitivity in executing Saro Wiwa.

But he also expected more of the people of Nigeria.

It is of no use for Nigerian leaders to shout from abroad and not to ensure that the fires of resistance are burning inside Nigeria.

In our case (in South Africa), we recognised the importance of some of the leaders of the liberation movement going abroad to mobilise international opinion behind the liberation movement. Nevertheless, international support was merely subordinate to what we were doing inside the country during the most difficult times.

Our people inside the country went underground to mobilise because our organisation was banned. Our people were arrested, detained without trial for months on end. Some were tortured and killed by the police in police custody. Some were thrown in jail to serve life. Others were shot down, massacred on many occasions, during peaceful street demonstrations. But we did not flinch.

Mandela continued his efforts as a member of the Commonwealth Monitoring and Action Group. As the two-year deadline and the next Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting approached – in 1997 in Edinburgh – Mandela telephoned Abacha and wrote to him to remind him that the lifting of the suspension would require at least the release of Chief Mosood Abiola, General Olusegun Obasanjo and the detained Ogoni leaders.

He also suggested, in response to security concerns raised by Abacha, that arrangements could be made to receive Obasanjo and Abiola outside of the country, and possibly in South Africa, while elections were being prepared, provided they would be able to return to Nigeria to contest the elections.694

Abacha did not comply by the time the Commonwealth met and Nigeria’s suspension was extended.695 It was only when Abacha died soon after this, that Obasanjo was released. General Yar’Adua died in prison, and so did Abiola, the day he was to be released.

Abacha was succeeded by General Abubakar and the transition to democratic civilian rule began. A direct link between Mandela and Abubakar was established through General Nyanda, Head of the SANDF. Nyanda had met Abubakar at a seminar in Nigeria on militarism and democracy, and the two became close to each other.696 ‘When General Abubakar took over,’ Mandela explained, ‘through his connection with Nyanda he was able to make an approach to us that South Africa should get involved in seeking a solution to the impasse in that country.’697

The Nigeria issue sharply demonstrated the limits of intervention by individual countries, even with a president to whom countries paid great respect. At the same time, the collective effort of the most powerful multilateral organisations also failed to move Abacha. The impact of this issue on South Africa’s foreign policy stance, and that of Mandela, fused with a broader shift in foreign policy towards still greater salience of multilateralism, though without closing the space for interventions by President Mandela.

I can call him so you can talk to each other and start the relations afresh