The National Party withdrawal from the Government of National Unity had made 1996 a pivotal year for the evolution of strategy. The closure of the RDP Office at about the same time and then the adoption of GEAR as government’s macroeconomic strategy broadened the issues and sharpened debates. The moment the NP withdrawal was announced an ad hoc NEC committee was established to reflect on the implications and make recommendations. The most immediate issues related to party politics and the state.

Given that the NP had withdrawn and no other party had won enough votes in 1994 to be entitled to a post of deputy president, what did it mean for the IFP’s participation in the executive? The question of whether the ANC had the capacity to manage the consequences in KwaZulu of forcing the IFP out of the government, discouraged any who had such thoughts. The NEC rather took the view that it might provide an opportunity for the ANC to improve relations with the IFP, now that the two parties would be governing the country together. The debate on relations with the IFP was to continue, with some advocating closer relations or even a merger. There were strong rumours in the run-up to the ANC’s 1997 national conference of such a possible merger – and of an offer of the post of the country’s deputy presidency to Buthelezi to help promote peace in KwaZulu-Natal – but neither of those things happened. However, when asked about these rumours in a TV interview on the eve of the Conference, Mandela studiously and persistently talked about 'unity' in general, and broadened this to apply to parties beyond the IFP.

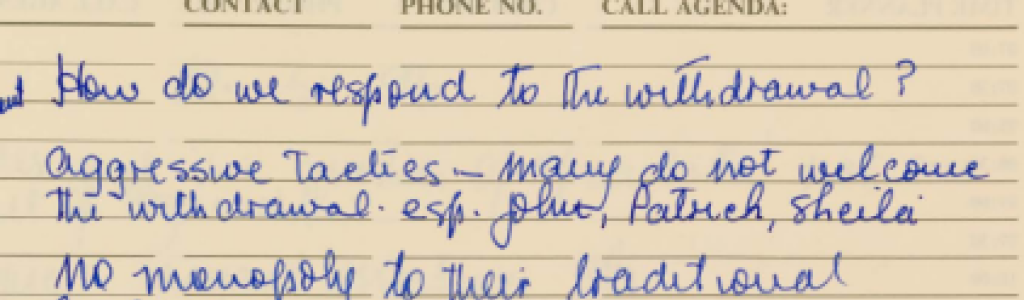

Regarding the National Party, the assessment was that it would adopt the strongly oppositional stance that its restive structures and parliamentary caucus had been demanding, and that it would project itself in Coloured, Indian and White communities as protector of minority rights that were threatened by the ANC. Mandela thought a swift and forceful response was needed, noting that many amongst the NP leadership did not welcome the withdrawal. It was also, he thought, an opportunity to step up efforts to work to win support within the NPs base – ‘no party’, he observed, had ‘a monopoly over its traditional constituencies.’752

This development renewed thinking within the ANC about the ‘national question’, effectively the process of building a non-racial society with equality for all regardless of which community they belonged to. The debate was given more urgency by reports of growing reservations amongst Coloured, Indian and White communities about whether the ANC would fulfil its commitments to towards them.753

Beyond party political questions, the NP withdrawal from the Government of National Unity spurred consolidation of the executive and faster transformation of the public service. It lent impetus to building the planning and coordination capacity missing from the presidency given the shriveled office that was inherited from the De Klerk government.

The call for better coordination was reinforced by a view that the development and adoption of GEAR had been insufficiently coordinated within government’s economic departments.754 It was this macro-economic policy and the dissolution of the RDP office that fueled the most intensive debates, in the ANC and the Alliance. Within the ANC there was surprise, even shock, at such decisions being taken without sufficient consultation, since it was argued that they constituted a change of policy. Whether or not they did, and whether or not the RDP had been abandoned and replaced by GEAR, was the core of the debate. The ANC leadership in government insisted that the RDP remained the framework of government’s programme and that GEAR was an elaboration of the macroeconomic approach referred to in Ready to Govern and the RDP. It was a set of measures, they argued, which in the context of the inherited macroeconomic crisis and the integration of South Africa in the world economy, would ensure that the resources would be available for implementation of the RDP.

Although the NEC supported the macroeconomic framework in August 1996 and although the 1997 National conference resolved the debate, the tensions persisted, combined with a labelling of the so-called ‘1996 class project’ that became the stock-in-trade of discourse within the Alliance.