‘For or against GEAR’, many saw as the principal question in the run up to the 1997 conference. It drove lobbying and shaped nominations for elective office, giving rise to competing lists of preferred candidates. Jay Naidoo and Alec Erwin, though originating in the trade union movement, were not on the Cosatu list of nominees, reflecting perceptions of their part as government ministers in the adoption of GEAR.

The 1997 election of Thabo Mbeki as president of the ANC and consequently future president of the country, was effectively a forgone conclusion. Mandela had sought to manage things that way after Mbeki had been appointed the country’s deputy president in 1994 and ANC deputy president later the same year. His resolve to serve only one term had been made irreversible, deliberately, by his announcing it early on and repeatedly confirming it. In doing so he took care to address a public tendency, domestic and foreign, to regard the prospect of his leaving the presidency with foreboding. When remarks he made in 1996 about his legacy were taken as hints of illness and imminent death, he felt the need to confront the issue in a personal press article. Besides the general public anxiety occasioned by such a prospect, coverage in some media sought to contrast him with his successor, to belittle the latter and to portend doom and gloom ‘when Mandela goes.’

On 19 February 1996, at Potchefstroom University, I restated my testament: my desire to bring about reconciliation among South Africans - African, Coloured, Indian and white.

I also said that, as I near the end of my days, my determination to pursue these objectives will be even stronger. This I pronounced from the fullness of my convictions.

But is it correct for the President to talk about this, some have genuinely asked. Won't this plunge the country into turmoil? I hope this short article will lay these concerns to rest.

Let me restate the obvious: I have long passed my teens; and the distance to my final destination is shorter than the road I have trudged over the years! What nature has decreed should not generate undue insecurity.

In any case, as I have indicated on countless occasions, I do not intend to continue in office after the end of this term.

There is no doubt that the broader population, serious investors and politicians have internalised this fact. The confidence in South Africa's future is reflected in the expansion of long-term fixed investments, the unfolding growth and development strategy and constitutional negotiations - all of which are laying the foundation for our progress well beyond the beginning of the new millennium.

A ridiculous notion is sometimes advanced that Mandela has been exclusively responsible for these real achievements of the South African people, particularly our smooth transition.

If only to emphasise that I am human, and as fallible as anyone else, let me admit that these accolades do flatter me. So too, does the Sunday Times editor's attribution to me of ‘warmth of spirit and generosity’, in the edition of 18 February.

The compliment is genuinely appreciated, as long as it does not present the President as ‘superhuman’ and create the impression that the ANC - with its thousands of leaders and millions of supporters - is a mere rubber stamp of my ideas; and that the ministers, experts and others are all insignificant, under the magic spell of a single individual.

Further, we should all be proud that success of worldwide significance has come out of a down-trodden people - out of Africa! Yes, Africans, with their supposed venality and incompetence achieved this feat! Thus I find quite distressing any insinuation that I do not belong to these African masses and do not share their aspirations.

Those who forecast doom for South Africa, suggest that I, alone, among presidents of the ANC over the last 84 years, have created such a situation that, once I retire, the ANC will not be able to constitute a leadership collective, which will remain loyal to the policies of the movement - policies which I was directed to pursue while I was President, including nation-building and reconciliation.

This is what was intimated when Chief Albert Luthuli was president of the ANC. Few knew of Oliver Tambo and his outstanding qualities. But, when the baton changed hands, Tambo ably rose to the challenge, building the ANC, under very difficult conditions, into a formidable force.

I have on countless occasions explained how I matured, politically, within the ranks of a movement and a leadership that were critical in shaping my outlook. I am a product of the mire that our society was. On occasion, like other leaders, I have stumbled; and cannot claim to sparkle alone on a glorified perch.

Let me indulge the reader by citing three recent examples. I will exercise a bit of licence and may reveal information that has not as yet been made public.

In 1990, a number of leaders, including Joe Slovo, proposed that we should suspend armed actions. Because nothing much had come out of the fledgling negotiations, I was taken aback: I was not convinced that it was the wisest thing to do. But after much discussion and soul-searching, I concurred; and the movement took that decision.

Later, it became clear that elements in the government were, by omission or commission, involved in the violence. Occasionally, issues came to a head with strange massacres. Except in the case of Boipatong and one or two others, my insistence that we suspend negotiations would be thrown out by the National Executive Committee.

Then there was the ANC Strategic Perspectives on enforced coalition. It took a lot of persuasion to convince me that that was the correct route to take - instead of direct majority rule and a voluntary decision by the majority party to take others on board.

Now, this should make me a Devil and other ANC leaders Angels!

But such an approach would be way off the mark. The ANC I lead has a rich tradition of frank discussion, looking at problems from different angles and synthesising ideas to reach balanced decisions.

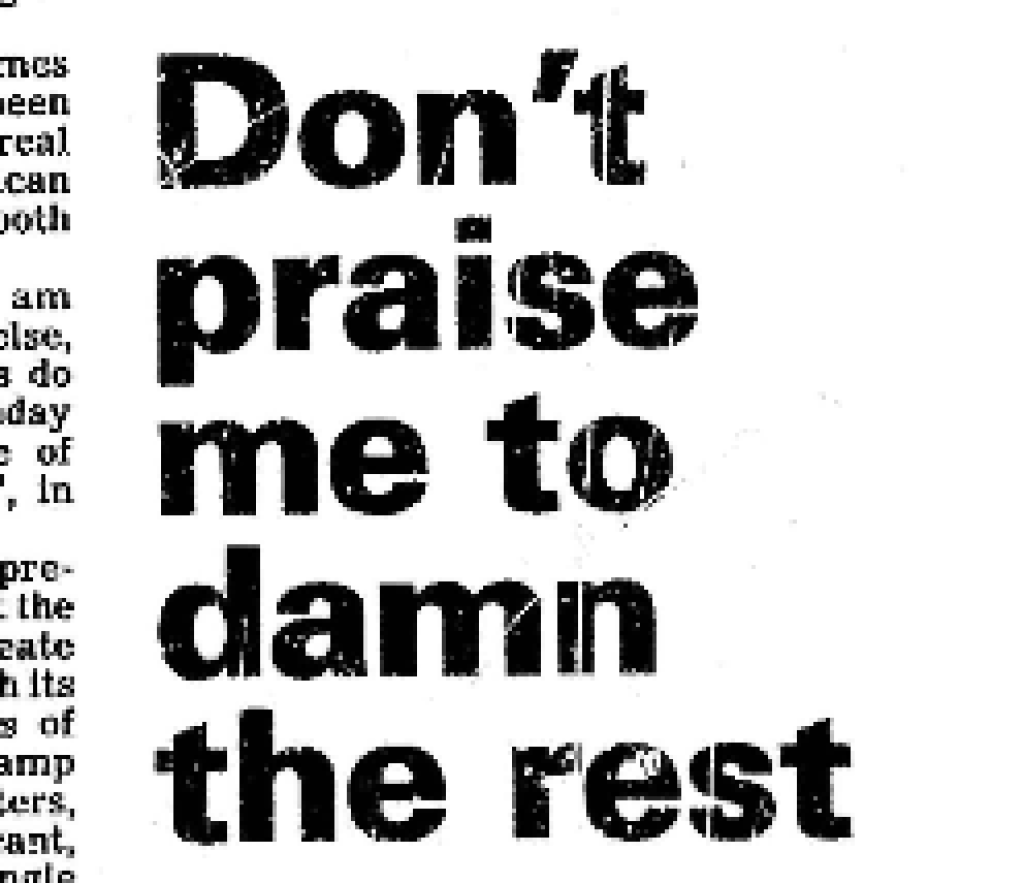

It is particularly unacceptable that this strain of hero-worshipping should be coupled with a systematic campaign to denigrate other ANC leaders such as Deputy-President Thabo Mbeki - a campaign that is beyond any civilised norms of discourse, let alone objectivity. Further, an attempt is made to decide who should be in the leadership of the ANC, and whom I should have in Cabinet. The exaltation of the President, and denigration of other ANC leaders, constitutes praise which I do not accept.

Yes, I see nation-building and reconciliation as my mission: a mission of the ANC. The ideal of liberating all racial groups from past divisions aside; this is a strategy based on realism. For, none of the former enemies has vanquished the other. Through persuasion, and in line with the constitution, we should together build a democratic and prosperous society, at peace with itself.

At the opening of parliament this year, I emphasised that healing and building are a two-way process, which should receive the support of all South Africans. Reconciliation cannot be attained without reconstruction and development, and vice versa. And I should strongly emphasise that the mission of reconciliation is underpinned by what I have dedicated my life to: uplifting the most down-trodden sections of our population and all-round transformation of society. In fact, the new patriotism is emerging because the great majority of citizens are taking up this challenge.

This majority - both black and white - did play its part, to varying degrees, in making our miracle happen. They have not taken the idiom of ‘miracle’ too literally; and they're not sitting back, believing that an individual, to whom super-human qualities are conveniently ascribed, will make our nation succeed.

Supported by this majority, the liberation movement, to which I belong, is making every effort to ensure the establishment of enduring institutions of democracy and respect for human rights, which will outlive any personality.

As for the wild rumours about my health, there is little that is new. When we were on Robben Island, enemies of democracy concocted stories that I once had died and, at another time, was ‘busy dying’.

In continuing to confirm his intention to step down, he would increasingly add his regard for Thabo Mbeki as someone who might succeed him.

What is clear is that a man of 81 cannot really lead a robust country such as ours. Our young democracy would require a comparatively young leadership, and we have excellent material in the ANC, and I have not the slightest doubt that the young people who are leading this organisation will probably stand head and shoulders above the present President when they have been given the opportunity to lead. ... Oh yes, I do intend on stepping down in 1999, whether it will be before or after is a matter that would be addressed by the leadership of the organisation. ...

On the eve of the ANC’s 1997 conference, Mandela returned to the theme.

As far as the presidency of the country is concerned, I have already pointed out that I am a de jure President and Thabo Mbeki is already a de facto President of the country. I am pushing everything to him and I’m a ceremonial president. They can ask me any day to hand over all powers to Thabo Mbeki – he is the man who is already running the government of the country. And my stepping down will be very smooth, it won’t bring about any disruption. I will enjoy my last year as ceremonial president.764

So, given what was more or less a consensus, it was not the election of the ANC President that drew the most anticipation and tension as the 50th National Conference approached, but that of the ANC’s deputy president.

Many in the national leadership favoured Jacob Zuma for the position. In a climate charged with policy differences and criticisms of government, including from the left of the political spectrum, they were anxious to ensure the election of their candidate.

Initially there were two other nominations – Mathews Phosa , the premier of Mpumalanga province and Winnie Mandela. Phosa withdrew after being urged to do so by Nelson Mandela, who was worried, it seems, that if Phosa was elected, his leaving the province would unleash a power struggle for provincial positions. His withdrawal, suggesting a gathering unanimity, also had the effect of increasing the odds against the success of Winnie Mandela’s bid. A combination of intense lobbying and debate culminated in the Women’s League withdrawing Winnie Mandela’s nomination. Undeterred, she was left with the option of nomination from the conference floor which, as a result of a rule change made before the conference, would have required the vote of 25 percent of the accredited delegates (instead of the previous 10 percent. In the event, her nomination received even less than the old threshold and she withdrew. Asked in an interview on the eve of the conference if he had been part of any discussions about Winnie Mandela’s future in politics, Mandela skirted the question.765

Thabo Mbeki and Jacob Zuma were therefore elected without contest to become president and deputy president of the ANC.

With regard to policy, as well as macroeconomic policy the conference also took decisions to strengthen the organisation, including emphasis on mass organization and mobilisation, political education and adoption of the principles contained in the document about quality of leadership, Through the Eye of the Needle. The conference also resolved that the posts of secretary-general, treasurer-general and deputy secretary-general should be full-time, and decided that national conferences should be held every five years rather than three years as had been the case.

There were aspects of the political report Mandela presented which elicited strong and negative reaction from the media and non-governmental organisations. One was an observation about the role of the media in opposing measures aimed at ending racial disparities (see Chapter 4 on communication). Another was on the role of some NGOs, indicating that the ANC’s sensitivity to criticism by (formerly) allied organisations including NGOs, was growing, partly based on the belief that it was unfair, and partly because there was concern that these organisations could mobilise the ANC constituency around the pace of change.

If you don’t mind I wouldn’t like to be pressed beyond that.

Our experience of the last three years points to the importance of non-governmental organisations (NGOs), community-based organisations (CBOs) and grassroots-based political formations in ensuring popular participation in governance.

The effective and admirable way in which many of these structures have functioned has served to emphasise the point that, in many instances, the public service, however efficient it may be, may not be the best instrument to mobilise for popular involvement and participation.

However, we must also draw attention to the fact that many of our non-governmental organisations are not in fact NGO's, both because they have no popular base and the actuality that they rely on the domestic and foreign governments, rather than the people, for their material sustenance.

As we continue the struggle to ensure a people-driven process of social transformation, we will have to consider the reliability of such NGOs as a vehicle to achieve this objective.

Though Mandela expressed strong feelings about the public reaction to these comments in written reflections before the conference closed, (see Chapter 5), he simply observed in his closing remarks to the conference that the reactions were ‘not unexpected.’

Those reflections also included thoughts, which he added to the prepared speech, on the strengths and responsibilities emanating from the ANC’s tradition of uncontested election of leaders and on his own experience of the challenges of being in that position, during which there had been moments at which he did not consider himself bound by the principle of collective leadership.

Last Wednesday Comrade Thabo Mbeki was elected unopposed as President of the African National Congress, I congratulate him for that honour. The election is a fitting tribute to his leadership of the youth in this country, to his brilliant performance in various capacities in exile, to the impressive contribution which he made is as part of the ANC team in the negotiations in Codesa and to the brilliant manner in which he has carried out his duties as Deputy President of the ANC and the government….

The time had come to take leave. In doing so he drew from history; but with optimism for the future.

The time has come to hand over the baton in a relay that started more than 85 years ago in Mangaung; nay more, centuries ago when the warriors of Autshumayo, Makhanda, Mzilikazi, Moshweshwe, Khama, Sekhukhuni, Lobatsibeni, Cetshwayo, Nghunghunyane, Uithalder and Ramabulana, laid down their lives to defend the dignity and integrity of their being as a people.

When we ourselves received the baton from Dube, Sol Plaatje, Ghandi, Abdul Abduraman, Charlotte Maxeke, Gumede, Mahabane and others, we might not have fully appreciated the significance of the occasion, preoccupied as we were by the detail of the moment. Yet, in their mysterious ways, history and fate were about to dictate to us that we should walk the valley of death again and again before we reached the mountain-tops of the people`s desires.

And so the time has come to make way for a new generation, secure in the knowledge that despite our numerous mistakes, we sought to serve the cause of freedom; if we stumbled on occasion, the bruises sustained were the mark of the lessons that we had to learn to make our humble contribution to the birth of our nation; so our people can start, after the interregnum of defeat and humiliation, to build their lives afresh as masters of their own collective destiny.

If we were fortunate to smell the sweet scent of freedom, there are many more who deserved, perhaps more than us, to be here to witness the rise of a generation that they nurtured. But for the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, Oliver Tambo, Moses Kotane, Yusuf Dadoo, JB Marks, Lilian Ngoyi, Florence Mophosho, Kate Molale, Alex LaGuma, Helen Joseph, Joe Slovo, Bram Fischer, Moses Mabhida, Ruth First and others would have been witness to the end of a lap in a relay that they ran with such energy and devotion.

It is in their name that we say, … here are the reins of the movement - protect and guard its precious legacy; defend its unity and integrity as committed disciples of change; pursue its popular objectives like true revolutionaries who seek only to serve the nation.

If we make these demands on you, it is because you accepted the burden of responsibility when you decided to enter the ranks of this leading movement of fundamental change. You responded to the call of destiny to bring into reality the day when the people can indeed govern.

If we make these demands on you, it is because you have run such a successful Conference - demonstrating for all to see, the quality of the ANC as the principal agent of social change. In the content of our resolutions, in the spirit of comradeship which characterised our communion over the last five days, this 50th National Conference of the ANC has demonstrated once more the strength of internal democracy in our organisation, inspired by the search for answers to the challenges that face us. …

Running like a golden thread through the decisions that we have taken is a reaffirmation of what the ANC has always stood for:

- to bring fundamental change to the lives of all South Africans, especially the poor;

- to recognise the actual contradictions in our society and to state them boldly, the better to search for their resolution;

- to avoid steps that further worsen social conflict; and

- to build our new nation by continually and consciously exorcising the demon of tribalism, racism and religious intolerance.

If these objectives are themselves not new; the circumstances in which they have to be pursued are different: we operate in a world which is searching for a better life - without the imprisonment of dogma. In this sense, therefore, you have started along a new path into the new century.

More often than not, an epoch creates and nurtures the individuals which are associated with its twist and turns. And so a name becomes the symbol of an era.

As we hand over the baton, it is appropriate that I should thank the ANC for shaping me as such a symbol of what it stands for. I know that the love and respect that I have enjoyed is love and respect for the ANC and its ideals. I know that the world-wide appreciation of South Africa`s miracle and the dignity of its people is appreciation, first and foremost, of the work of the ANC.

In the early years when I was all green and raw in the movement`s ranks, Constatine Ramohanoe, the Transvaal President of the ANC took me by train and on foot to visit villages, cities and dorpies, and taught me and my generation never to lose touch with the people.

During that period, Moses Kotane, in his curt and disciplinarian manner showed us ways of nurturing people`s thinking and commitment to the poor. Yusuf Dadoo brought to the fore the importance of united action among all the oppressed and democratic forces. Bram Fischer and Michael Harmel brought us into the debates of the Communist Party and assisted us to appreciate that problems need to be approached from different angles. Chief Albert Luthuli taught us that reconciliation is not an antithesis to revolutionary struggle and transformation.

And Oliver Tambo, was like no one else a brother and a friend to me. He enriched my own life and intellect; and neither I nor indeed this country can forget this colossus of our history.

All these giants and more - the living and the dead - were the band of comrades who not only compensated for my own weaknesses; but they also assigned me tasks where my strengths could grow and thrive. What I am today is because of them; it is because of the ANC; it is because of the Tripartite Alliance.

But I think that this experience transcends my own life and touches on the very issue of cadre policy. ... I say so because I know that … there are many who have such great potential - revolutionaries suited to the new age: organisers, intellectuals, mass leaders, activists and strategists at all levels of the movement. We must nurture you all, and let your strengths shine through.

The time has come to hand over the baton. And I personally relish the moment when my fellow veterans and I shall be able to observe from near and judge from afar. As 1999 approaches, I will endeavour as State President to delegate more and more responsibility, so as to ensure a smooth transition to the new Presidency.

Thus I will be able to have that opportunity in my last years to spoil my grandchildren and try in various ways to assist all South African children, especially those who have been the hapless victims of a system that did not care. I will also have more time to continue the debates with Chopo [Walter Sisulu], Zizi [Govan Mbeki] and others, which the 20 years of umrabulo [political education and debates] on the Island could not resolve.

…in my humble way, I shall continue to be of service to transformation, and to the ANC, the only movement that is capable of bringing about that transformation. As an ordinary member of the ANC I suppose that I will also have many privileges that I have been deprived of over the years: to be as critical as I can be; to challenge any signs of ‘autocracy from Shell House’; and to lobby for my preferred candidates from the branch level upwards.

On a more serious note though, I wish to reiterate that I will remain a disciplined member of the ANC; and in my last months in government office, I will always be guided by the ANC`s policies, and find mechanisms that will allow you to rap me over the knuckles for any indiscretions.

Our generation traversed a century that was characterised by conflict, bloodshed, hatred and intolerance; a century which tried but could not fully resolve the problems of disparity between the rich and the poor, between developing and developed countries.

I hope that our endeavours as the ANC have contributed and will continue to contribute to this search for a just world order.

Today marks the completion of one more lap in that relay race - still to continue for many more decades - when we take leave so that the competent, generation of lawyers, computer experts, economists, financiers, industrialists, doctors, lawyers, engineers and above all ordinary workers and peasants can take the ANC into the new millennium.