If instability in Lesotho was a threat to the region’s pursuit of integrated development, peace and stability, even more so were instability in the Great Lakes region and spreading civil war in Zaire.

Zaire was admitted as a member of the SADC in 1996, with the support of Mandela. There were misgivings on the part of several SADC members who, according to President Masire, felt it hard to say no to Mandela.654 There were others who welcomed the expansion of SADC as a way of diluting South African power in the region.655 Whatever the arguments, the reality was that instability in the Congo, and more broadly the Great Lakes region, impacted on most of the SADC countries.

South Africa’s involvement with the Zaire conflict began with agreement in late 1996 to participate in a multinational force being established in eastern Zaire to cope with instability arising from an estimated one million refugees from genocide in neighbouring Rwanda. In that context President Sese Seke Mobutu asked South Africa to facilitate talks between the Zairean government and Laurent Kabila’s Alliance of Democratic Forces (ADF) which had established itself in the East and was advancing towards Zaire’s capital, Kinshasa. There followed a series of proximity talks in South Africa during February 1997, Kabila’s ADF having been persuaded by the United States government to participate.656

The talks opened the way to face-to-face discussions between President Mobutu and Laurent Kabila, on 4 May aboard a South African naval ship at the port of Pointe Noire at the mouth of the Congo River. A Special Representative of the United Nations and OAU was there.

Mandela believed – falsely it turned out – that a resolution to the conflict could be achieved by summoning leadership qualities from the two protagonists, persuading the aging and ill Mobutu to leave office with dignity and Kabila to accept an inclusive approach to forming a new government.

But the advance of the rebel forces lessened Kabila’s interest in an inclusive solution. His attitude, and failure to arrive at follow-up talks on the ship ten days after the first talks, despite having agreed to do so (Kabila gave fears for his security as his reason for not joining the talks), and public vacillation in his position, angered Mandela who upbraided him by telephone in earshot of the media. It was arranged for Kabila to come the next day to Cape Town so that Mandela could brief him on the proposals drawn up after the first meeting and which had been widely consulted with governments in Africa, France and the United States. While on board the ship Mandela also phoned several heads of state in the region to discourage them from military intervention in the DRC.657

Madiba played a big role

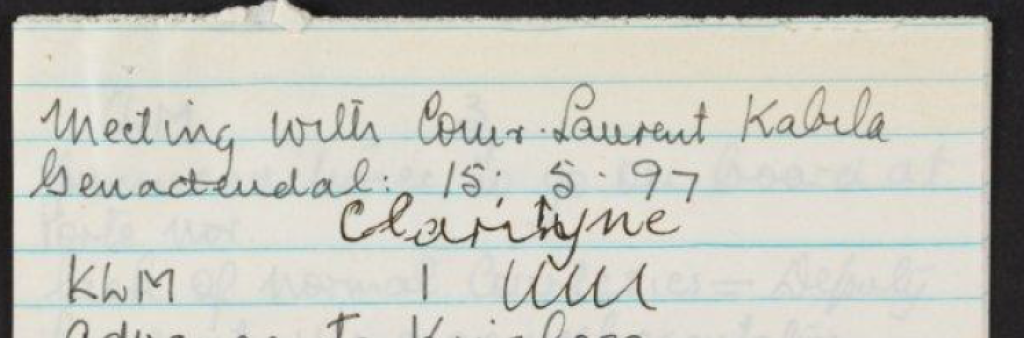

At the meeting in South Africa, Mandela harshly took Kabila to task. His notes for the meeting convey the anger fired by Kabila’s behaviour, by his violation of Mandela’s trust and by the lack of the kind of leadership Mandela believed essential to peaceful resolution of conflict. Having noted that Kabila had kept advancing to Kinshasa despite having undertaken not to do so, almost every line of Mandela’s note is annotated ‘KLM’ for ‘emphasis’:

- Advance to Kinshasa

Bizima Karaha statement

Surround but don’t attack Something grossly wrong with one who makes a firm and clear statement and later denies making statement. Tends to destroy mutual confidence and respect that should exist among comrades.

Understands your concern over security

But many people find your claim ridiculous, to say the least.Promised twice to go on board at Pointe-Noire

Lack of normal courtesies = Deputy President [Mbeki], UNO [United Nations] and OAU representative, President Mobutu.

Kept us waiting for whole day without any information of your whereabouts

Unfortunate attitude towards a dying man, insensitive, no human feelings, no respect.

Martti Ahtisaari – famous int. diplomatLack of appreciation for the enormous expenses at taxpayers’ cost that my country has spent, ship itself

30 soldiers.[You have been] rushing to the press.

Your image being tarnished; no longer have the moral high ground.

Unfortunate things being said about you. [I] have defended you and I am sure others as well have done so.

Sadako Ogata

Kofi Annan[Have] given me tough job. But you are busy destroying mutual trust.

How can I serve [a] person who treats me without respect?658

In Mandela’s briefing of the press after the meeting, there was not a hint of this angry lecture. That was consistent with his usual approach to negotiations: that nothing should be done to publicly diminish parties to negotiation.

I was in the Congo yesterday with Deputy President Thabo Mbeki. We met President Mobutu and made certain proposals to him which he requested to take back to Kinshasa to consult his advisors. We are expecting an answer from him on Monday.

The President of the Alliance of the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo-Zaire, Comrade Kabila, came to see us today to give us the opportunity of briefing him on the discussions we had with President Mobutu. We have done so and we are all waiting for the response from President Mobutu.

Now as you know in the past we have been very candid in placing these matters before the media but we are engaged in very sensitive and complicated negotiations and we don’t want any party to hear about the discussions that we have had with the other from the media because that further complicates our negotiations. All that I want to say is that matters are going according to plan and we are confident that a solution will be found because we are getting co-operation from both parties; but I hope you won’t probe us for details.

I just want to make a brief statement. As you know I was in the Congo yesterday with the Deputy President Thabo Mbeki.

But Mobutu fled the country and Kabila advanced on the capital – encouraged by some Western diplomats in Kinshasa who seemingly feared the consequences of a lack of government and breakdown of law and order,660 and soon took power in what then became the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Having eschewed the inclusive route that had been agreed, Kabila found his government challenged by rebels less than two years later. His appeal to SADC for military support precipitated SADC’s most serious crisis.

On the one hand Mandela as SADC chairperson, with the support of most member states, insisted that a negotiated resolution of the problem was needed, and that any military intervention would need United Nations support.661 On the other hand, President Mugabe, still chairman of the Organ on Politics, Security and Defence, organised a process through the Organ culminating in agreement to lend military assistance to Kabila’s government, known as the Victoria Falls Initiative, ostensibly in the name of SADC, and with the support of Angola and Namibia whose troops joined those of Zimbabwe.

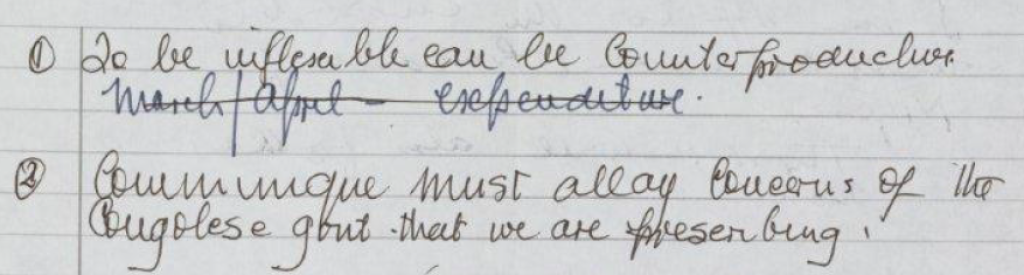

Alarmed by this visible divide in SADC, by invective accusing him and South Africa of hypocrisy and concerned at the potential for the conflict to expand into regional conflict, Mandela convened an emergency SADC summit in Pretoria (Kabila and Mugabe stayed away though their countries were represented). The purpose of the summit and its outcome was to begin bridging the divide opened by SADC’s dual response to Kabila’s call for help. As SADC’s chair, Mandela was focused on the organisation’s unity, which required of him to put aside his public criticism of Mugabe’s approach. As president of South Africa he wanted to displace perceptions that he was using South Africa’s power to enforce his own views. As a democrat, he affirmed the rights of the people and government of the DRC. The brief notes he jotted in the meeting speak succinctly to these priorities.

To be inflexible can be counterproductive.

Communique must allay concerns of Congolese govt. that we are prescribing.

No question of rivalry between Victoria Falls & Pretoria

Minorities – structures must be seen to be representative …

Responsibility for settlement rests with the govt & people of DRC.662

The Summit communiqué called for an immediate cease-fire, a troop standstill and the initiation of a peaceful process of political dialogue aimed at finding a solution. Mandela was mandated to pursue these goals in consultation with the OAU secretary-general, and to harmonise SADC’s approach with the Victoria Falls initiative.

A few days later the UN Security Council called for a peaceful resolution and withdrawal of foreign forces and mandated the UN secretary general to consult with the OAU and the region to find a solution. That same week, in talks alongside the Non-Aligned Movement Summit in Durban, the UN secretary general, Kofi Annan, negotiated a strategy providing for withdrawal of foreign troops; and an interim political structure to oversee a democratic transition, as well as the deployment of a combined UN and OAU peacekeeping force.663

Mandela addressed the issue ten days later at the SADC summit in Mauritius, seamlessly embracing both approaches.

We are encouraged by the progress in the Victoria Falls initiative towards securing peace in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and in staving off a conflict which threatened to involve the whole region. That progress is a tribute to the quality of leadership that Africa has produced.

The challenge now is to develop and implement the agreements so that the people of the DRC can determine their own destiny and embark on reconstruction as a united, democratic, stable and prosperous nation; and so that the independence and security of all the countries of Southern Africa and the Great Lakes region are secure.

For SADC this means exercising its responsibility, working together with the Organisation of African Unity, to create the mechanisms which will ensure progress towards processes which will ultimately result in genuinely democratic elections.

To all intents and purposes, the breach in SADC was closed, though tensions remained. The DRC crisis was a seminal moment in SADC’s evolution, linking conflict resolution to both negotiation and peace keeping within the multilateral framework of the United Nations and OAU.

Contained within the experience in the DRC were several lessons about managing complex situations that involved many interests, both regional and international. Besides the historical involvement of Belgium, the United States and France, as well as the interests of the nine countries sharing borders with the DRC, there were a multitude of private sector interests premised on the DRC’s massive and often rare natural endowments. In a sense, South Africa – in trying to facilitate an amicable settlement – was punching far above its weight; and it needed in future to weigh all these factors more intensely before committing itself to such processes.

However, on balance, the seed had been planted, and southern African was steadily inching towards peace, democracy and stability. The final months of Mandela’s term as president of South Africa and chair of SADC, marked the beginning of a new phase of SADC’s contribution to regional peace, stability and development within a framework in which the linkages between democratisation, peace, stability and development were more clearly and more tightly drawn.