Shared past and common aspirations were not enough to ensure a smooth transition from a state of virtual siege to regional cooperation peace, stability and democracy. Consequences of the colonial past and South Africa’s economic domination, as well as persistence of political tensions in some countries, tested regional institutions and commitments even as they were maturing. Attitudes to South Africa shaped by the past had to ease: South Africa needed to make clear that its economic weight and military strength would not be used to dominate629 even though some powers outside the continent wanted South Africa to play such a role.630

The Southern African Development Co-ordinating Conference had been formed in 1980 by heads of independent states to coordinate investment and trade and to reduce economic dependence on South Africa. In 1992 with Namibia now independent and South Africa in transition to democracy, the co-coordinating conference was transformed into the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and its focus shifted towards economic integration.

When South Africa achieved democracy, the Front Line States grouping dissolved to become SADC’s political and security wing. This was formalised when the SADC Summit of 1996 agreed to establish the SADC Organ on Politics, Defence and Security Cooperation. But just how the Organ fitted within the SADC framework was not thought through and it became a point of contention.

Mandela was elected to chair SADC for a three year term beginning in September 1996. At his first summit meeting as chairperson – reflecting the concerns of the new democratic government – he broached challenges that SADC was grappling with in combining development and security roles, and in reconciling respect for the member states’ sovereignty with commitment to democratic principles that might not be fully realised in all the states.

We have to ask frank questions and give honest answers about the state we are in and where we intend to go. We have to assess our capacities and review our strategies if we are to achieve the noble ideals that SADC stands for.

The task of transforming SADC into a dynamic development community is an urgent one. ... To assess the impact of SADC's policies and strategies, its structures and practices, and to review their relevance for regional integration, is of fundamental importance. That is because it is only when they are seen by the majority of our people to have an effect on their own everyday life that SADC will continue to have a legitimate reason to exist. All of us have an obligation to show the courage, vision and determination to transform SADC into a major role player in continental and global affairs.

One of the imperatives we face is to involve civil society in the affairs of SADC. And indeed remarkable progress has been made in engaging key stakeholders such as the private sector and civic associations in the development of the sectoral protocols that will guide regional integration. As we consider today, amongst other things, the approval of protocols in areas like education, mining and cross-border movement of people, it is a source of great satisfaction to known that our signatures will be coming at the tail-end of long consultation with stakeholders who helped determine the priorities.

This Summit is expected to pronounce itself on a number of issues of great concern to the people of Southern Africa: gender equality; productivity; and the ban on production, use and stockpiling of anti-personnel landmines in our region.

I have no doubt that all of us will take a firm stand on matters so critical to the socio-economic advancement of our people. SADC will want to give concrete content to its unequivocal recognition that gender equality is a fundamental human right to be realised through equitable representation of women and men in decision making structures as well as equal access to resources. We do understand that productivity and competitiveness are indispensable weapons in our war against poverty, deprivation and marginalisation. And we cannot rest until Southern Africa is safe for our children to play with innocent abandon, free from the savage threat of millions of explosive weapons recklessly scattered across the region.

It is also our task to review recent political developments in the region and elsewhere and to raise our collective voice of concern where necessary.

Our dream of Africa's rebirth as we enter the new millennium, depends as much as anything on each country and each regional grouping in the continent, committing itself to the principles of democracy, respect for human rights and the basic tenets of good governance.

SADC as a regional grouping largely owes its origin precisely to a commitment to those principles, values and ideals. Indeed they are embodied in the Treaty which binds us together. SADC was forged in the furnace of courageous resistance to Apartheid's racist minority rule and destabilisation; to its gross violations of the human rights of most of its citizens as well as those of the people in the entire sub-region; and to its massive corruption of the organs of government. This heroic aspect of our legacy, if nothing else, obliges us to a principled defence and promotion of these principles in our own midst and on our continent. Amongst the Heads of State here today are persons who, because of their commitment to the overthrow of dictatorial regimes, were forced into exile; who spent long years in the prisons of their oppressors; who hazarded their lives to wage underground struggles; and who, with the multitude of their people, suffered great hardship and danger.

Amongst SADC's basic principles are respect for the sovereignty of member states and non-interference in one another's internal affairs. This is the basis of good governance on the inter-state level. But these considerations cannot blunt or totally override our common concern for democracy, human rights and good governance in all of our constituent states. Our Treaty obligations bind us to undertake measures to promote the achievement of the SADC's objectives and to refrain from any measures likely to jeopardise the sustenance of these principles.

It is alien to SADC to tolerate the domination of society by any part of it. The right of citizens to participate unhindered in political activities in the country of their birth right is a non-negotiable basic principle to which we all subscribe. The creation of structures within which public opinion can be mobilised and given public expression is undeniably part of the democratic process.

This democratic process is denied when political leaders, representing a legitimate body of opinion, are prevented from participating in political activity. We, collectively, cannot remain silent when political or civil movements are harassed and suppressed through harsh state action. We all support, and strive for, the creation of a society in which all stakeholders: labour, business and other elements of civil society can play a meaningful role for the betterment of all.

It is also contrary to the spirit of the Treaty binding us that absolute power be exercised by a state institution. While we respect traditional authority and provide for its expression in government and legislative structures, constitutional evolution and reform is incumbent on each member state. Nor can nominal but ineffective commitment to such reform be acceptable without the whole region ultimately being destabilised.

At some point therefore, we, as a regional organisation, must reflect on how far we support the democratic process and respect for human rights. Can we continue to give comfort to member states whose actions go so diametrically against the values and principles we hold so dear and for which we struggled so long and so hard? Where we have, as we sadly do, instances of member states denying their citizens these basic rights, what should we as an organisation do or say?

These are difficult questions. But we have to ponder them seriously if we wish to retain credibility as an organisation genuinely committed to democracy, human rights and good governance - and, perhaps even more importantly, if we are to have as our supreme mission the eradication of the suffering - social, economic and political - of the people of our region and its constituent countries.

There was one issue that Mandela’s remarks did not touch on – how the Organ on Politics, Defence and Security Cooperation fitted in. It had been the subject of intense debate over the past months. The day before the summit opened, the Organ on Politics, Defence and Security Cooperation met, chaired by President Robert Mugabe. It had been established as a structure that would ‘operate at the Summit level, and ... function independently of other SADC structures’.632 Mandela was not entirely convinced.

1. Attended SADC summit in Gaborone in June 1996 and agreed with the decision to form the Organ.

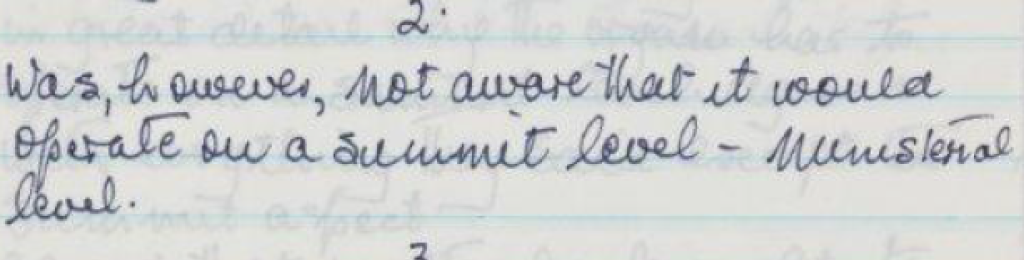

2. Was, however, not aware that it would operate on a summit level [rather than a] ministerial level.

3. Discovered when we met in Luanda on 1 October 1996 that Organ was itself a summit. Came to me as shock –

Unaware of existence of any organisation.

They may be

Had I known, I would not have accepted chairmanship [of the SADC].

4. Then travelled all the way to see President Mugabe to discuss issue. Thereafter saw Pres. Masire as my predecessor and Pres. Chissano as Vice Chairman.

Later the four of us met in Cape Town.

5. On all these occasions they explained in great detail why the Organ had to operate on a summit level. Agreed with everything they said except the summit aspect.

Agreed that matter be brought to this [Blantyre, Malawi] Summit.

6. Met the 2 Presidents in Gaborone and suggested solution.633

The next day the summit heard the members’ views, with no clear consensus emerging other than that there was need for the Organ, given the region’s challenges. The decision was postponed and Mandela was urged not to resign.634 Another discussion six months later at a meeting of heads of state in Maputo again ended without resolution, but there was greater consensus that the Organ should be a subcommittee of SADC rather than a separate entity.635

The matter was only resolved some years later by the 2001 summit, with the adoption of a Protocol on Politics, Defence and security Co-operation that formalised the Organ’s status as an integral part of SADC, chaired for a year by a member of the summit who is not the chairperson of SADC.

By then views had been tempered by the experience of SADC’s political or military interventions in Lesotho, Swaziland, Angola and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, among others.

Although the matter continued to be a source of tension between Mandela and Mugabe, they worked together on various issues, maintaining an uneasy rapport that evolved over the years.636