What kind of office would be needed to serve Nelson Mandela’s presidency? Rather than plan structures without the benefit of knowledge about existing permutations, and experience, the ANC entered government without initially changing structures. But even in that context, the situation in the presidency was unique. Only at the centre of government, did President Mandela and Deputy President Mbeki have to start virtually from scratch.

There were two kinds of experience elsewhere in the public service. By the time of the election, a small but significant number of ANC people were inserted into foreign affairs; and the ANC and security forces, in particular defence and intelligence, had done extensive joint planning for integration. In other departments, while there was not always a full complement of senior staff, the new ministers generally found a director-general or acting director-general from the previous administration. They were not always at ease with what they found, in particular where it involved people with an intelligence background; and there was a need to bring in knowledge and understanding of the ANC’s mandate and policies - but at least there was a structure in place.

When P W Botha was President, the State President’s Office was the nexus of the National Security Management System National Security Management System. Although initially introduced to coordinate security departments, it came to oversee and coordinate almost all of government’s functions, driven by imperatives of containing and repressing resistance. It was dominated by the military and other security departments, and reached across government and down from national level to localities. Every department had a desk in the Union Buildings staffed by senior officials and there were a number of situation rooms.70 De Klerk, along with most other non-security ministers had been somewhat marginalised in the system, and when he became president, he dismantled the system to free the office of constraints on his programme. The desks and situation rooms were shut down and the officials returned to their departments. From 500 the Presidency staff complement was reduced to about 90.71 The business of coordination and oversight of policy and implementation was to be the function of the cabinet and its committees, in effect of the National Party. That suited a government which was focused on negotiations and transition, and was circumscribed from undertaking major policy initiatives.

So when Nelson Mandela walked into the Union Buildings on 10 May 1994, Deputy President De Klerk, leading a minority party in the Government of National Unity, had a fully functioning office staffed by people who had worked with him in the presidency for years. Deputy President Thabo Mbeki’s new office was still to be established. The RDP Office was also new. The president’s private office was denuded of staff. The ‘establishment’ – the legacy structure for the whole of the President’s Office – had little linkage to state departments except through the Cabinet. With the Cabinet now a multi-party executive of a Government of National Unity, emphasising a consensual approach rather than decisive action, the capacity for coherent coordination was further diluted.

Mandela’s office was in time given distinctive shape by the imprint on the inherited structure, of his own conception and practice of leadership and the imperatives of transition.

Building the office combined two aspects. One was bringing in senior liberation movement figures to head sections and act as advisers who understood the leadership Mandela had in mind. The other was not rushing to change the structure or dispense with staff from the old order

It was not always straightforward. Ways had to be found of accommodating generally rigid and cumbersome public service procedures to the urgent need to fill vacancies and to the imperatives of transformation. Sometimes special dispensations had to be made to diverge from normal procedure. Because some people had qualifications gained in exile that were not recognised at that time in South Africa, they were appointed initially at lower levels than matched their roles, experience and abilities.

In the first week a human resource specialist was deployed to the presidency from the Department of Agriculture, with assistants from the Department of Public Service, to deal with the business of advertising posts; handling the flood of applications from thousands wanting to serve the country’s first democratically elected president and advising on the application of the rules.

But even if the rules were sometimes bent or broken to deal with the ‘abnormal’ circumstances, the Public Service Act proved a drag on the pace of change – President Mandela and Deputy President Mbeki bore the delays and obstructions with patience, some of their officials less so.72

The process began with key senior appointments.

in the beginning it was difficult to employ people at that level

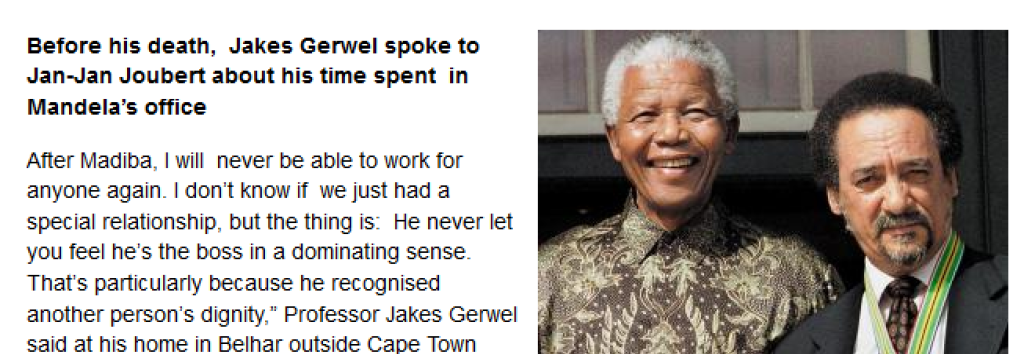

Jakes Gerwel was the first senior appointment, as director-general and Cabinet Secretary. After his name was suggested by Mbeki, who had had contact with him for some years, Mandela also consulted with the Western Cape ANC leadership and people who had been student activists at the University of the Western Cape when Gerwel was vice-chancellor.73 Gerwel brought a political background of leadership of the United Democratic Front (UDF); and engagement with the ANC in exile. As vice-chancellor of the University of the Western Cape, a position from which he was about to retire, he had led the transformation of an apartheid university into ‘an intellectual home of the left’.

Madiba did not know Jakes at that time … he wanted to know everything there was to know about Jakes

Professor Jakes Gerwel was Secretary of the Cabinet as well as Director-General during my Presidency, positions he held with distinction.

He is now Chairperson of the Nelson Mandela Foundation, the Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC), the African Centre for Constructive Resolution of Disputes (ACCORD), the Institute for Democracy in South Africa (IDASA) and the Institute for Justice and Reconciliation.

He is also active in the private sector, being Chairperson of Brimstone Investment Corporation, Africon Engineering International, Educor-Naspers, Director of Naspers, Old Mutual, David Phillips Publishers, Western Province Cricket Pty Ltd, member of the South African Academy of Science and six other private sector organisations. He is a former Chairperson of the Committee of University Principals.

Academically he has acquitted himself exceptionally. He passed the Bachelor of Arts Degree, Bachelor of Arts Honours, Dr Litterarum et Philosophiae, all cum laude. He has no less that six honorary degrees from local and overseas universities.

He has been honoured with the South African Order of the Southern Cross, Gold, by the President of South Africa (1999),King Abdulaziz Sash, Minister Rank, by Crown Prince Abdullah of Saudi Arabia (1999) and the Order of Good Deeds by Colonel Muammar Gaddafi of Libya (1999).

His publications include a variety of monographs, articles, essays and papers on literary, educational and socio-political subjects.

He is an impressive and fearlessly independent thinker who rose to the position of Rector of the University of Western Cape, and now Chancellor of the University of Rhodes.

In the field of human relations, he clearly emerges as a true leader who is devoid of paranoiac tendencies and who encourages principled discussions. He constantly draws attention to those aspects among comrades which are designed to strengthen rather than weaken human relations.

As Chairperson of our Foundation, he is a linchpin in keeping all of us working together harmoniously, and he nips in the bud any incipient developments towards any form of in-fighting among comrades.

Few people are aware that he is also a polished negotiator on the international level. It was him and His Royal Highness Prince Bandar, the Saudi Arabian Ambassador to Washington, who were responsible for the Lockerbie breakthrough.

Ahmed Kathrada was there from the start, as an adviser to the president. His position was only formalised after some months when he was appointed to the newly-created post of parliamentary counsellor. A long-time comrade, friend, and fellow prisoner, he had turned down a suggestion that he become a cabinet minister.

What had happened is that the papers had published beforehand their cabinet and my name was there. I then wrote to him and also gave the letter to someone to make sure in case mine doesn’t reach him, saying that although my name has been mentioned I am not interested in being in the Cabinet. It didn’t reach him so that when his first announcement came in the papers I was a minister. Fortunately there was this bartering with the IFP which wanted one of the security portfolios, so the easiest thing was to give mine.75

he didn’t like manoeuvre. Some of it was quite straightforward, because I didn’t give him any trouble on this question

Fink Haysom became Mandela’s legal adviser. He had played a central role in the constitutional negotiations, and during this process Mandela had relied on his advice.76 He brought a background as a legal academic and a labour and human rights lawyer who had also been active in combating vigilante and state-sponsored violence since the 1980s. After Mandela’s presidency he was involved in the Burundi peace process, which Mandela was facilitating and later served in senior positions in the United Nations with responsibility for conflict resolution. The role of legal adviser had gained new weight with South Africa becoming constitutional state--every executive action had to be tested against the constitution, in effect against rules, many of which were only implied. The Constitution specifies that any decision by the President that is taken in terms of legislation or has legal consequences must be done in writing. As South Africa set about creating the framework of laws and agencies to transform the country and re-enter the international community, Mandela was signing some 800 executive orders each year,77 on average two each day.

Joel Netshitenzhe joined the office to head communications. He was a member of the ANC’s National Executive Committee and National Working Committee, with a background in communication and strategic analysis. With him was Parks Mankahlana, who attended to liaison with the media. Parks, who came to the Office from the executive committee of the ANC Youth League, developed an excellent and open relationship with the media.

As is the case in many parts of the world, south Africa has produced a harvest of bright stars, even geniuses, who have helped to transform our country from its painful past, and made it world famous. It is these women and men right across the colour line, who surprised the world in the nineties, a world which hailed South Africa as a miracle country. That response from the international community confirmed once again what we have repeatedly said before, namely, that our wealth does not depend only in our minerals, but also in the calibre of our women and men. Joel Netshitenzhe, Head of the Governments Communication Service, is an integral part of that wealth.

Joel Netshitenzhe could be polite and controlled in the face of unbearable provocation. In the numerous meetings I attended with him as President of the ANC and the country, I have never seen him once losing his temper. In this regard he worked cordially with Thabo who sometimes would volunteer to help write the speech.

When Rusty Evans retired as Director-General of the Department of Foreign Affairs, I requested Joel to succeed Rusty. Joel was as polite as usual. But he said that if I insisted he would consider the offer, but added emphatically that he would prefer to remain in Communications. I tried hard to pressurise him. But with a broad smile across his face he persisted in his courteous refusal.

These senior officials formed a small, cohesive and effective team of like mind and temperament, interacting without formality to give direction to a small private presidential office that was aligned with Mandela’s own personality, priorities and conception of leadership. They worked in ways that did not always conform to what people might have assumed.

When Jakes became DG we had one president and two deputies. So there was this whole President’s Office and Jakes as the DG would have to sign lots of documents which had to go through De Klerk and had to go through Thabo. So I went to Jakes and said ‘Jakes, you must sign these things because you’re holding up the works,’ and he said, ‘Let me tell you something Essop, I am the DG of Mandela, I’m not the DG of Mbeki and De Klerk.’ I said, ‘My friend, we can’t move because these people don’t have the authority to sign.’ So he said, ‘Bring me as little as you can to sign because my job is to serve Madiba.’ I went back to the deputy president and said, ‘Well, this is Jakes’s view’, and he said, ‘Well I think Jakes is correct, let’s find another way … Jakes is correct, this is a new government, the president has to deal with many things. It is correct that Jakes should concentrate the bulk of his energies in serving Madiba.’79

Jakes Gerwel explained later, that he wanted a small office with a focused task:

I just decided that a big bureaucracy would not work. We worked quite separately [from Deputy President Thabo Mbeki’s office], that was Madiba’s style. That’s the way Madiba operated. I think he would have died in a big presidency like Thabo’s even, or like this one [of Jacob Zuma]. Fink was saying recently that ‘now that I am sitting in the UN, the more I appreciate your approach – the smaller the more efficient’.80

Although Gerwel’s view – and that of the President – was that the office should be ‘as lean as efficiency allows’81 , the office was even smaller than that. As he noted in correspondence with the Department of State Expenditure, when they ‘entered the office in May 1994 - then already into the 1994/5 financial year - we essentially inherited the apartheid era Presidential office. Just as some examples: the dramatically enlarged democracy, the rapidly burgeoning international relations, the historical position and stature of President Mandela, all of which had profound implications for the functioning of the Office of the President, could not be and were not taken into consideration at that stage.’82

Jakes Gerwel not only combined the work of Director-General and Cabinet Secretary - he was also political adviser. He became the main channel through which information and communication flowed to and from Mandela, whether it was with the deputy president’s office or ministers,83 except for issues in which Mandela took a special interest.84 He also acted as an envoy to give effect to several of Mandela’s international interventions which would normally have been handled by the Department of Foreign Affairs.85

Ahmed Kathrada’s job as parliamentary counsellor also differed from what might have been expected. As he explains, ‘contrary to perceptions people have, that this is a very senior position, it was just a title’. Whilst Mandela did use him for things relating to Parliament, much of his work was to do with Mandela’s correspondence, informed by his understanding of the president’s priorities and approach: drafting responses to letters from heads of state and others, and referring letters to ministers to deal with the matter. The civil servants in the office who were from the apartheid days would also come to him for guidance on draft replies to letters to the president.86

Joel Netshitenzhe’s communication unit likewise extended its work beyond the norm, to include systematic monitoring and analysis not only of communication media but also of government performance across the departments. In this way it mitigated the initial absence of institutionalised capacity in the presidency for coordinating and evaluating policy and its implementation.

the President ...has consistently held the view … that his staff complement should be kept as lean as efficiency allows

From my point of view it was just a title

In taking decisions, the president combined readiness to consult his advisers and others on the one hand, with confidence on the other in the opinions he formed that made it often difficult to move him once he had adopted a position – if ultimately he realised that he was not changing people’s minds, he might concede, but not easily.

He also had the ability, according to Jakes Gerwel, ‘to simplify and get through a thing. Madiba was very straightforward.’

I spent my entire life in universities. Theorising comes naturally to me. I am suspicious about simple answers, but I had to hear so many times, ‘Jakes, it must be simpler than that’. ...Madiba could see the essential core and make things simple. He could therefore make a crucial decision – within five minutes, if necessary.87

He drew not only on the advisers in this office but kept closely involved with the ANC. To do so he initiated the practice which continued after his presidency, of treating Monday as ‘ANC day’ in the President’s diary, spent at the ANC Head Office with the top officials and others. He attended National Working Committee meetings. He also consulted with other ANC leaders, among them Walter Sisulu, and not only on Mondays:

Me in particular he likes to ring. He wakes me up, one o’clock, two o’clock, it doesn’t matter. I realise after he has woken me up that this thing is not so important – well, we discuss it, but it didn’t really require that he wake me up at that time.88

Mandela’s involvement in Cabinet altered over time. In the early days he kept abreast of almost all aspects of policy, hands-on, partly in response to necessities of maintaining ANC coherence in a Government of National Unity and navigating through the many-faceted choices to be made as the massive and complex task of transformation took hold. The day before Cabinet meetings he convened ANC ministers and deputy ministers in an ANC Cabinet Caucus at his Cape Town residence, Genadendal.

During that tenure Madiba’s role was fundamentally important and hands-on.

One thing he did, in appreciation of the fact that it was a Government of National Unity, when Parliament was in session was to convene us at Genadendal for supper in the dining room on the night before the Cabinet meeting so that we could caucus positions that we wanted to take and be mutually supportive. It afforded comrades to have a discussion that was quite free.89

There were other meetings with ministers through which Mandela would interact to guide processes or give support. There would often be very early morning phone calls to get ministers to meetings or lobbying of Ministers to support a position he held. The interventions dealt with a wide range of issues, among them some described elsewhere in this account: ensuring funds for the priority programmes of the first hundred days in government90 ; tightly managing the appointment of successive finance ministers; resolving differences between ministers over aspects of labour legislation; finalising the list of public holidays; shepherding ANC ministers regarding the location of Parliament. Where peace, violence and stability were concerned, his interventions were continuous and direct.91

Apart from the business of government and ANC, Mandela didn’t hesitate to telephone or invite to a meeting anyone with whom he thought it necessary to discuss matters: ministers, representatives or leaders of sectors of society, heads of state. He often called people himself rather than asking his assistants to do so and sometimes took action that caught even those close to him unawares.

His engagement with society was an intense and mutual relationship. People from every corner of society wanted to interact with him, and he wanted to interact with them, both leaders and ordinary people and their communities. It sustained an acute sensitivity to public opinion and mood.

when we came into government, there was this issue of what we would do during the first hundred days

Madiba would phone you at four a.m. because at that time he was up, and he had read something in the newspapers

And it was not just South Africans. As Mary Mxadana, Mandela’s private secretary, observed: ‘He’s not only an ordinary president of a country, but he’s a renowned leader so everyone wants to have his time.’ When he was supposed to be at rest, unless it was in a place with no phone and his cell-phone was taken away, ‘he will start calling people all over the world’.92