Inheriting a shell of a private office without staff and little or no linkage to the rest of government except through the Cabinet, Mandela exercised leadership in a style emphasising political and personal influence rather than the formal integrating and coordinating systems familiar in contemporary government. The development of such systems for oversight and detailed management of government was delegated, though not entirely, to Deputy President Mbeki.

The way Mandela related to his staff, his acceptance and reassurance of employees from the old order; his readiness to make the existing structure work rather than rush to remodel it, were consistent with the overall approach to transition as a phased transformation whose early days required as much attention to stability as to change. It also reflected his own preoccupation, as a manager of a delicate transition.

The morning after the inauguration Mandela arrived at the back entrance of the West Wing of the Union Buildings at about ten o’clock in the morning, with a security detail made up of still to be integrated members of the South African Police and members of Umkhonto weSizwe. With him, from his ANC office, were Barbara Masekela and Jessie Duarte . He had come that morning from the State Guest House in Pretoria where he had spent the night and which was to be his temporary official Pretoria residence for the next three months while FW De Klerk was moving out of the presidential residence, Libertas, later to be renamed by Mandela himself as Mahlambandlopfu (Bathing of Elephants or more precisely Dawn in xiTsonga).

The main business of that first day was the finalisation of the Cabinet of the Government of National Unity and the swearing in of ministers, but before that he went to the office where he had previously met with De Klerk as president of the apartheid government, but which was now his own office.

When he had gone to those meetings with De Klerk there was always a smell of coffee in the passage way, but on this morning there was no smell of coffee and except for the few people he had met at the entrance to the building, from the corridor the place seemed virtually deserted and forlorn, lacking any sense of human warmth.

A month before the inauguration a memo to Mandela’s ANC office from Dave Steward, De Klerk’s most senior official, pointed to what Mandela was to find. The memo defined two categories of staff in the State President’s Office, as it was then known. Firstly, there were those providing ‘functional and administrative services’. The second group was made up of those providing ‘personal services – including private and appointments secretaries, typists and clerks dealing with presidential correspondence and telephone enquiries; media advisers and spokespersons; speechwriters/advisers; security personnel and domestic personnel. ... It is accepted in the present system,’ the memo said, ‘that the President himself should appoint officials in this category’.53

Accordingly, De Klerk took the whole of his private office with him to his new office as one of the executive deputy presidents, leaving only the ‘functional and administrative staff’.

Before the election the sub-Council on Foreign Affairs of the Transitional Executive Council (TEC) that had been given the responsibility of preparing for the inauguration, was also tasked with discussing the structure of the new president’s office.54 But it made little headway beyond designating a small temporary team from the Department of Foreign Affairs to receive the new president in his office and support him in the first few days. The team was headed by Dr Chris Streeter who had been working with the sub-Council – he was asked by Thabo Mbeki to take on the role, after discussion with Pik Botha, the minister of foreign affairs. Streeter became effectively Mandela’s ‘chief of staff’ for a while after the election results were announced until the director-general was appointed. His first task was to arrange Mandela’s flight to Cape Town for the sitting of Parliament that was to elect him, accompany him on that trip and return to Pretoria to be in the office on Mandela’s first day.55

'Remember we’re a freedom movement. We’ve never been in government'

The situation made for some confusion and tension amongst officials in the Union Buildings.56

The only two senior staff left in the President’s Office were the head of corporate services, Fanie Pretorius, and the head of cabinet services, William Smith. Along with the rest of the ‘functional and administrative’ staff, they had no idea what to expect; who would be coming with Mandela; or what was expected of them. Would the ANC and President Mandela accept them to work in the office, they wondered. They were unaware of the communication between President De Klerk’s private office and the ANC or of the TEC process and had been unsuccessful in trying to meet with ANC officials to understand what would be wanted of them.57

The evening before President Mandela was due, William Smith, on his way to check if the office was ready, saw boxes stacked in the kitchen. In the boxes was new crockery and cutlery–everything from the previous period, he was told, had been taken to De Klerk’s new office because it had the old coat of arms. It was to be replaced by what was in the boxes. Other boxes contained new computers and office equipment. Everything was hastily unpacked and the machines connected.

Early the next morning, checking the private office before Mandela arrived, Smith was surprised to find there someone he didn’t know – she was, she told him, part of the foreign affairs team, the first indication of the existence and presence of the team.

Around ten o’clock the police alerted the officials that the president was on his way. When he arrived at the back entrance Mandela greeted them and went straight to his new office, where he told Chris Streeter he would like to give a message to the staff. Fanie Pretorius, head of services, was called

I was issuing instructions all over the place, and he says ‘Where did you come from to give us instructions?’’

She said she was part of a foreign affairs team … to assist the process of coming into the Union Buildings

Within five to ten minutes I received a call from the foreign affairs staff saying that the president would like to see me. Someone must have told him I was one of the senior guys. The two of us were the most senior staff members that Mr De Klerk did not take along. I almost ran up the stairs for this wonderful occasion, but I was also anxious because of the uncertainty: what was I about to hear from the president? ...

He started right away, he didn’t make any small talk. He said, ‘We know that staff here probably expect us to get rid of them. But that is not the nature of our organisation. We need your assistance because this is all new to us and I want you to tell the staff here that if they do their work properly they must feel comfortable’ – that is the word he used, ‘comfortable’ – ‘that they can stay and do their job. But’, he added, ‘we do need transformation, it can’t stay the same; there must be transformation.’ ...

I said, ‘Thank you very much for the kind message, I’ll be quite happy to do that but, Mr President, it would have so much more meaning if you were able to do it yourself’. He was taken aback and sat thinking for a second or two before he said, ‘Well, how long will it take?’ I said, ‘15 minutes, 20 minutes to get the staff together.’ And he said, ‘All right, do that.’

When we entered, the whole big room was packed with staff. It included the few black clerks, messengers and cleaners. They were all there, the whole office, every single staff member was there. You could hear a pin drop. When he entered he looked at them and said, ‘Well, I’m actually pressed for time, but I have to shake hands with each one of you’, and he started from the left side and shook hands with each and every staff member. About a quarter down the line he came to a lady who often had a stern looking face, though she was a friendly person. When he took her hand he said in Afrikaans, ‘Is jy kwaad vir my?’ and everybody started laughing. The ice was broken because he made a joke and everybody relaxed. He continued greeting the staff and then gave his message to them. Everybody was obviously very relieved.

He was Nelson Mandela at that moment, with the warmth and the acceptance. Everybody would have eaten out of his hand – there was no negative feeling from anybody after that in the staff, at least that we were aware of.58

Mandela later gave the same message in the same way to the fifty or so people working in the Tuynhuys in Cape Town on his first day there.59

The approach that forged trust and confidence on that first day helped ease the more diffuse and lingering unease between staff from the old administration and the new officials from the liberation movement. Mandela’s everyday way of engaging with the people who worked for him strengthened the bond, as did the way in which his new senior officials related with staff.

The many vacancies in the private office were not a product of fear of the future or antagonism to change, but the result of staff being taken to De Klerk’s office. Nevertheless, there were anxieties, worries rooted in what they had been taught to think of the ANC and of the majority of South Africans.60 For those who were there at the start, and for those who came later, the trust and commitment was consolidated by the courtesy and consideration Mandela showed each staff member, and by his use of Afrikaans – poor as his mastery was of the language – when meeting those whose language it was. The impact, as well as the contrast with how staff were treated in the previous times, is recalled whenever they remember their encounters with him.61 The progression from apprehension to confident loyalty is exemplified in the memoir of Zelda La Grange, his personal assistant during his Presidency and afterwards.62

Why were there so many vacancies? Was it the change of government and people feeling they weren’t welcome?

Gardeners (mainly Coloured folk) at the Westbrooke residence in Cape Town - which Mandela renamed Genadendal after the first mission station established in South Africa, to evangelise amongst the Khoi – told of how, ‘the first morning after he arrived he came out and greeted us. He once invited us into his house to take a couple of pictures with him. People couldn’t believe it.’ Previously, they had to remove themselves from the front of the house when De Klerk came home. ‘Every morning President Mandela gives us a nice wave and off he goes, we just pass by like normal people’.63

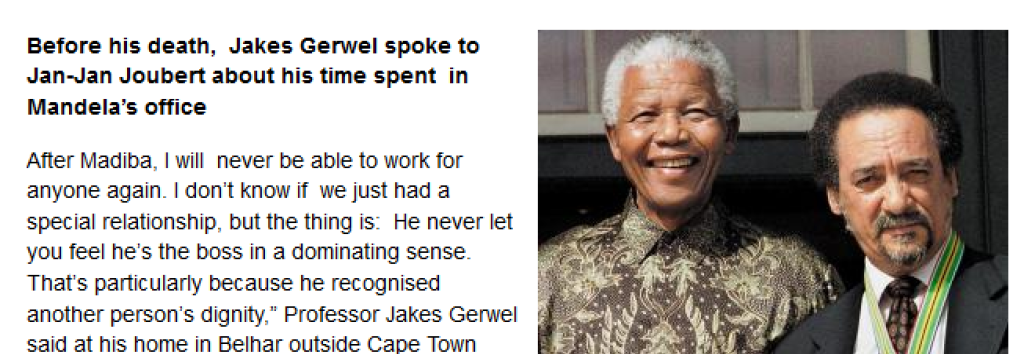

Those who worked in the office and residences, from gardeners, cleaners, clerks and typists to the most senior, speak consistently and with emotion of the consideration, respect and individual attention that they experienced from him. They describe him as generous, concerned about people who work in his office, easy-going, self-effacing, ‘knowing how to be an ordinary person’, with a sincerity demonstrated by his ‘greeting everybody in the same way where there is a camera on him or not’; ‘there is never this feeling that he is up there and you are down there’.64 He is ‘a people’s person who took to heart his own belief that you respect the dignity of the people around you.’65; ‘He never let you feel he’s the boss in a dominating sense. That’s particularly because he recognised another person’s dignity.’66 He was also very humane. He would meet you and not only ask about your work but also ask about the family.’67