Such was the intensity of Mandela’s involvement in communication as president that his office would get calls from the offices of presidents and prime ministers in other countries, advising against over-exposure of Mandela to the media. They were unaware that the initiatives which they admired but thought should be scaled down, originated from the president himself rather than his communication advisers. And beyond his own initiatives there were more invitations than could be accommodated to attend public and community events from sectors of society eager to engage with the President who symbolised the building of a new society. There were many requests for interviews from media organisations wanting a part of one of the biggest news stories of the time.

After a while Mandela found his programme too full. As his media liaison head, Parks Mankahlana, explained, during 1995 Mandela complained that his schedule left too little time to read state documents and the newspapers or to reflect on issues. He joked that he missed his days on Robben Island where he had time to think and suggested free time in the afternoon, whenever possible.586

That constraint, and the days regularly devoted to ANC work, along with the calendar of government and ANC business, set a framework within which a diary committee worked to shape a manageable programme that married the huge demand for Mandela’s time and his own objectives and plan. Consisting of the head of his private office and senior advisers, the committee devised as far as possible a programme with thematic coherence informed by the President’s priorities and focus for each period,

Powerful as the committee was, the programme bore the imprint of his own initiatives and judgment as a seasoned communicator. Its overall configuration owed much to his own understanding of the importance of communication and public relations to the wok of government, and the details reflected his close attention to public mood and what was in the newspapers and broadcast media.

Some of the most dramatic moments of communication were initiatives he took with little or no external advice, but which did much to shape public discourse and often displayed a flair for symbolism and timing.

Wearing the Springbok jersey at Ellis Park to celebrate South Africa’s victory in the 1995 Rugby World Cup and inviting the widows of apartheid leaders to tea and meeting Betsie Verwoerd, came to be defining moments for Afrikaners of reconciliation.

There were also moments when, stung by backlash in public commentary and media reports, he would retreat. Public reaction led him, with the help of advisers, to retreat from the surge of anger over the situation in KwaZulu that led to his statements on Shell House and on withdrawing funding from the province – what he had said, though, had helped focus minds on a more constructive approach. On the other hand, formulating GEAR as a ‘fundamental policy of the ANC’, negotiable only at the level of detail, did little to resolve tensions.

There were also the moments of anger at pivotal moments during negotiations and interventions to resolve conflict and tension, when he felt that his trust in the integrity of others had been betrayed.

The way he dressed made statements: eschewing top hat and tails for the inauguration in favour of the more egalitarian suit; formal attire for appearances in parliament; the Madiba shirt in interactive public engagements that closed the distance between government and the people and gave expression to the vibrancy of a new society in the making; ANC colours at party events.

His engagements with media were in part planned by advisers, and in part of his own making. He initiated a meeting with Afrikaans editors in 1995,587 when issues of amnesty and of the future of the Afrikaans language were burning topics amongst their readers. In1996 with rising tensions in KwaZulu-Natal as the constitution drafting process drew to an end, he invited the editors of newspapers in that province, to brief them on the situation in the province and to give a sense of what the government intended doing about it.588

He maintained direct relations with individual editors and journalists. He knew them by first name, black and white, and established a friendly but courteous and firm rapport with them at press conferences and other interactions. In this he was well-served by Parks Mankahlana who went out of his way to develop friendly relations with journalists and wouldn’t hesitate to make his way into newsrooms to offer stories.589 (Personnel officials in the office, familiar with a different kind of relationship with the media, were puzzled at how little time Parks spent at his desk.)

If Mandela had an issue to raise with editors or senior journalists he would phone them and as often as not, invite them for a meal, and put his point of view.

He tried to walk the tightrope and to react in such a way that there was no invasion of the right of the media to write and tell it as it is. What he tended to do would be to invite specific journalists to a breakfast. Then he would say, ‘Look this is what you said but this is in reality what the situation is.’ … That was how he tried to manage the situation.590

He invited me to breakfast but shrouded it - he said ‘I must come with my new bride’

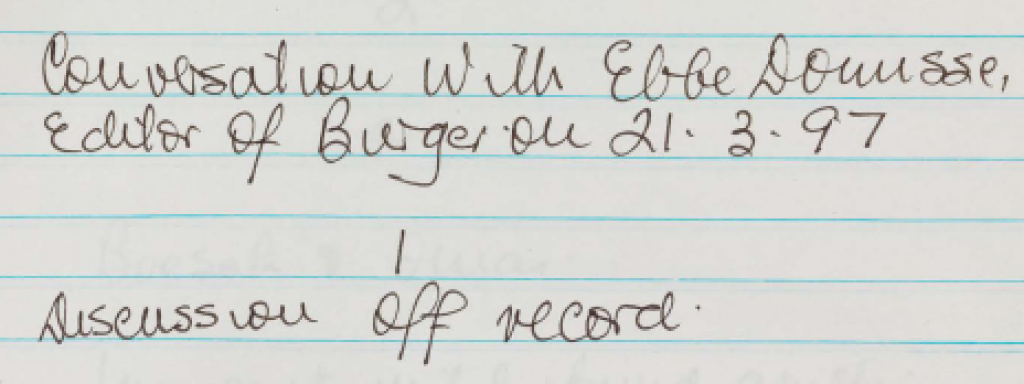

There were many such occasions. There was an off-the-record meeting with the editor of Die Burger newspaper when he felt the paper had given insufficient recognition to his explanation of the context of the Shell House shooting.591 He invited the editor of City Press who he felt had overlooked something important in an editorial arguing that Mandela was being used by the cricket and rugby bosses to make reconciliation a one-sided process favouring whites at black expense – both Mandela and the City Press editor agreed without any concessions that it was a useful discussion.

On the other hand, where policy or party politics were not at stake, he took a more relaxed attitude, exemplified in an incident during Mandela’s presidency, recounted by Jakes Gerwel. The Hustler magzne had a column entitled ‘Arsehole of the Month’: the president had been chosen for that month, and indignant voices outside the President’s Office were urging a distribution ban on the magazine. The president, in contrast, was highly amused and commented, ‘We should not be banning things.’592

Although Mandela received a daily analysis of the news media, soon after the working day began, he would by then have read several newspapers – and as often as not telephoned ministers and members of his communications team before sunrise to ask what they were doing about an issue featuring in the news.

He was happy to delegate the writing of speeches when he had confidence that they would reflect his views and priorities. There were times when he would indicate things that needed to be said and how they should be treated, especially for major events. But he knew too that what was not written in a prepared speech was the thing most likely to capture media attention, and for that reason did on occasion ask that important points should not be included in the prepared speech. Often, journalists covering his events would only prick their ears and take up their pens when he started speaking ex tempore. He would sometimes preface his remarks by saying that what he had just read was what his bosses told him to say; and now he would speak from the heart. On the other hand, his communication minders would tense up, knowing that some bombshell may be in offing – at the same time paying attention to the remarks as a guide for future communication.

There were times when Mandela was aware that what he believed needed saying would not find approval with those he consulted. What journalists described as ‘off the cuff’ and some in the ANC as ‘shooting from the hip’, were seldom spontaneous, but rather considered and prepared by him beforehand, sometimes as annotations to the prepared speech, and invariably precisely formulated. At times, aware that he could do so, he might assert strong positions with a view to opening debate that would end at a lesser position.

Frequent repetitions of positions over weeks, which he sometimes introduced with a self-deprecating remark that his staff told him he repeated himself too much, were not a symptom of forgetfulness – to shift opinion it was not enough merely to put a position on record, but sometimes to assert and re-assert it until it became a focus of public discourse. For example, the scorecard of expanding access to basic services became a mantra of communication in almost every kind of setting, formal or informal, prepared or unscripted, in speeches or notes.

The focus on relations with the media was part of a much broader effort of communication and public relations as a vital part of government work. As in the case of the media, democratising society required new emphasis on direct and unmediated communication with the people of South Africa, in all their sectors and formations, from villages and communities to professional associations and organised social formations; and representatives of every thread in the fabric of the society he was helping to fashion. This drew on the people’s forums of the ANC’s election campaign and also found expression in the Masakhane campaign, tailored to mobilise communities as agents of their own development.

He had his office engage with the VIP protection unit to loosen operational procedures that stopped him freely interacting with people.

The interactions were intense on both sides. Nothing gave him more strength than the constant and cherished affirmation by ordinary people from all races and all walks of life. It seemed always to give him an added fillip. The end of a day of interactions with the public would elicit a gait of self-satisfaction more than sitting in his office or in Cabinet and other meetings. ‘My batteries have been recharged’, he would remark. While he missed and demanded moments of quiet reflection, it would quite often be he himself who dropped everything to engage in one public event or another.

He knew that he had become an icon, in South Africa and across the world. He was sometimes bemused by it – hence his frequent jokes about not being recognised as a person – but he appreciated it as an asset to be nurtured for its power to move people. Learning with surprise on his release how fascinated journalists were with personal things about himself, he shared much. He took in his stride the intrusion this brought, as was the case in the newspaper project on ‘A day in the life of…’, when journalists spent a whole day observing him, something he accepted without a murmur, seemingly enjoying the glare.593

But he also drew lines, firmly yet tactfully, when the interest became intrusive and encroached on personal pain – with his divorce from Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, for instance, and his relationship with Graca Machel. When he and Graca Machel married, even his spokesperson was not told, leading him in all good faith to assure the media that there was no wedding at the very moment it was happening barely metres away!