Although, in part, the threat of civil war was averted when Constand Viljoen, the retired head of the South African Defence Force, decided in December 1993 to participate in the country’s founding democratic election, and to pursue Afrikaner self-determination through legal means, the way to the election was cleared only four days before the election, when Mandela signed the Accord on Afrikaner Self Determination between the Freedom Front, ANC and NP (see Chapter 1).478

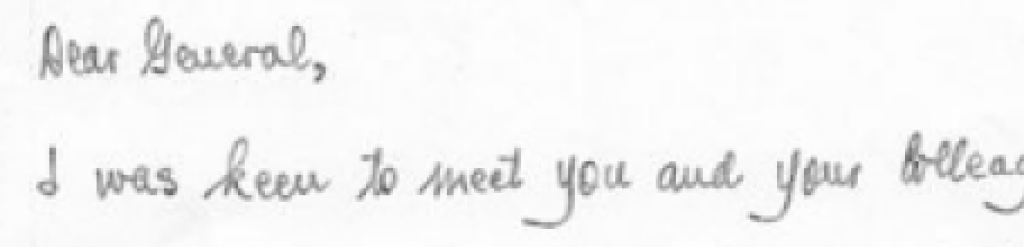

Mandela had missed the December meeting which marked the turning point, but sent Viljoen a letter signaling his support of the initiative:

the ANC kept on postponing the signing of the document

I was keen to meet you and your colleagues on Saturday 18 December 1993, and I regret it very much that this did not occur. I have now left for holiday until January 5, 1994, and hope to see you on my return.

Meanwhile I wish to let you know that the attached memorandum of agreement between the African National Congress and the Afrikaner Volksfront was discussed and approved by the officials of the ANC and it enjoys my support.479

The accord, signed by the National Party as well as the ANC, was a commitment to ‘to address, through a process of negotiations, the idea of Afrikaner self-determination, including the concept of a Volkstaat. A Volkstaat Council would be established to investigate and report to the Constitutional Assembly on measures which could give effect to that idea. Consideration of the idea would take into account ‘substantial proven support’ and consistency with the principles of democracy, non-racialism and fundamental rights, and the promotion of peace and national reconciliation. It was agreed that ‘proven support’ would be indicated by votes in the coming election for parties with a mandate to pursue the realisation of a Volkstaat.480

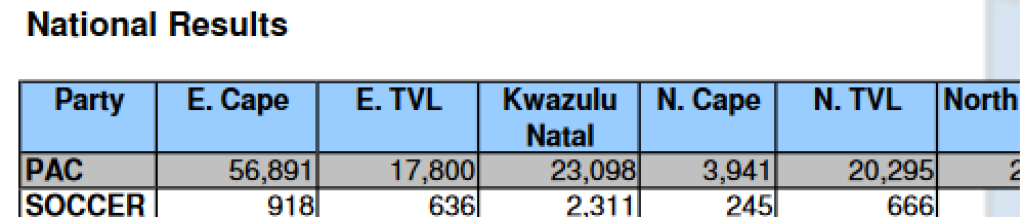

Votes for the Freedom Front totaled 425,000 in the national ballot and 640,000 in the provincial ballots. Some considered this enough support to warrant establishing the Volkstaat Council after the election.481

On the day that Mandela was to be elected President of the country, he broke from the ceremonial procession as he entered the National Assembly, to shake hands with Viljoen, now a Member of Parliament, saying he was glad they could find each other. After the inauguration, Viljoen says, Mandela told him that his office was open to him: ‘I have a great desire to be a president not only of the ANC but to be a president of everybody and I wish to give you free access to my office. If you have anything for the Afrikaner you would like to come and discuss, you can just ask.’ ‘And believe me,’ Viljoen says, ‘it never took more than two days to see the president if there was something I wanted to discuss.’482

After the election I had a most emotional moment at the opening of Parliament

Initially, the Volkstaat Council seemed a promising platform for the pursuit of Afrikaner self-determination. It was also the only such platform. When the Conservative Party refused to participate, arguing that it was restricted by the Constitution to producing options within a unitary state, and tried to negotiate directly with the President rather than through the council, they were rebuffed.483

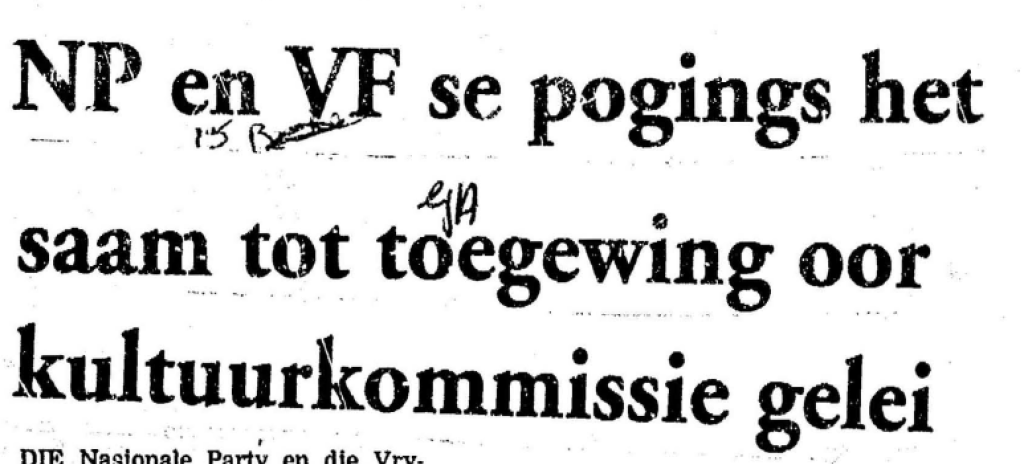

In the final days of constitutional negotiations Viljoen achieved two things. The continued existence of the Volkstaat Council made its way into the new constitution as a transitional institution.484 And agreement was reached, between the ANC on the one hand and the Freedom Front and National Party on the other, on constitutional recognition of rights of communities (voluntary communities as opposed to the groups imposed by apartheid law). 485This created a basis for the establishment of voluntary cultural councils in each sphere of government and a Commission for the Promotion and Protection of the Rights of Cultural, Religious and Linguistic Communities as one of the ‘Institutions supporting constitutional democracy.’486

But in the end the Volkstaat Council achieved little of substance towards self-determination. Its funding ceased in 1999. The legislation establishing it was repealed in 2001 and its reports went to the Commission.

As the council looked into the issue, it was confronted by the impossibility of finding a geographical base for Afrikaner autonomy and the emphasis shifted increasingly towards the notion of ‘cultural self-determination.’ But differences among those represented meant that little clarity emerged. This was highlighted in a rare altercation between Mandela and General Viljoen. In an impromptu media opportunity in April 1998 Mandela remarked that the continued call by some Afrikaner leaders for a separate homeland was insincere as they lacked enthusiasm for it.487 Angry reactions from General Viljoen and Hartzenberg drew from Mandela a reminder that the pre-election agreement had been conditional on resolving which of the several organisations claiming to represent Afrikaners genuinely did so – and that nothing had been done to do that. He made the same point again later in the Senate488

I therefore feel that they are not very enthusiastic about the idea of a volkstaat

as long as there is this division it would be difficult for Government to make a move

But there was more to it than the impossibility of geographical autonomy. Thabo Mbeki, reporting in 1999 to the National Assembly on discussions that he and Buthelezi had been having over the past two years with Afrikaner organisations, concluded that while there was a feeling of marginalization and disempowerment among many Afrikaners, there was also commitment to help build the new South Africa. In that context government would move urgently to set up the Commission for the Promotion of Cultural, Religious and Linguistic Rights provided for in the constitution, as a framework within which Afrikaners – and others defining themselves as communities – could pursue their community rights.489

The idea that the concerns needed either a separate territory or a political party dedicated only to the pursuit of Afrikaner rights had lost the hold it had had. When the 1999 election came, support for the Freedom Front – and by inference for the idea of self-determination – dropped precipitously. Its votes in provincial ballots fell from 640,000 in 1994 to 140,000 in 1999.490

The Volkstaat Council had provided space and time for the wish for self-determination to measure itself against the reality of a society which had entered a relatively calm normality after a peaceful election. The shift of political power played a part, as did reconciliation, in particular Mandela’s intense engagement with Afrikaner society. ‘It was Mandela,’ Constand Viljoen said in explanation of the waning support for self-determination, ‘Mandela mesmerised the Afrikaners. He was so acceptable. He created such a big expectation towards a real solution in South Africa that even the Afrikaner people accepted the ideas.’491

It was Mandela. Mandela mesmerised the Afrikaners

While the special institution created to pursue Afrikaner self-determination did little to advance that goal, it served a more fundamental purpose – it had, as Mandela and Thabo Mbeki observed on several occasions, saved the country from a destructive war492 and as a token of ANC good faith it eased adjustment to a democratic society.

Many of you do not know what dangers faced this country just before the elections