The tentative reform of traditional leadership, the approach of local elections and the national drafting of a new constitution raised the stakes for those who held sway in KwaZulu-Natal. Tension and violence mounted in early 1995 coupled with a boycott of the Constitutional Assembly.

The continuing violence and what he saw as inflammatory talk by the IFP evoked angry public intervention by Mandela. It began at a May Day rally in Umlazi in 1995, a week after Buthelezi had called on his supporters, in an address at the same stadium, to ‘rise up and resist central government’ if their constitutional demands were not met. Before Mandela addressed the rally, shots were fired from outside the stadium, and sounds of gunfire continued as he spoke. In a statement he had prepared but not discussed with other ANC leaders, he threatened to cut central government funding to the province:

[Inkatha] should know it is (central government) who is giving them money and they are using the money against my government ... should they continue, I’m going to withdraw the money.372

Caught by surprise the Office of the President briefed the media with a gloss on Mandela’s threat of action which, unqualified, would have been unconstitutional – it was a ‘timely warning’ to the provincial government.373

Mandela elaborated the next day in Parliament, taking into account the political storm that his remarks on withholding funds had unleashed.

. . .While political violence is a thing of the past in most parts of our country, this is not the case in parts of KwaZulu-Natal, as has been emphasised by other speakers. A reduction of tensions in that province is one of the most urgent priorities faced by politicians.

In this context, the provocative statements by some leaders in the province are a matter of concern. To call on members of the provincial government to ‘rise and resist’ the national Government, is to test the bounds of what is legal and legitimate. To call on people in such a context to fight the national Government for their freedom, is to do the same.

As President I have the task and duty to protect the Constitution and the democratic foundation on which it rests. Not to act when there is a threat to overthrow the Constitution would be a dereliction of duty.

Therefore I again wish to issue a timely warning, before matters develop still further in this direction, that the Government will not allow public funds at the disposal of the province to be used to finance an attempt to overthrow the Constitution by violence and unconstitutional means. Nor will the Government allow the use of such funds for the promotion of a reign of terror.

The central Government does not have the constitutional power to withhold funds from a provincial government working within the constitutional framework. To do so, would be contrary to my own democratic ideas.

Our political culture embraces differences between political parties and different levels of government.

But the Constitution does not protect attempts, using government funds or in any other way, to promote lawlessness and anarchy or to foment divisive and bloody war against fellow South Africans.

We hope that matters will not reach such a fearsome eventuality and that all matters fomenting tension will be resolved in a mature and peaceful manner.…

I have briefed the leaders of political parties on the latest developments in KwaZulu-Natal. This is against the background of more than 20 000 innocent people-men, women children and the aged-having been slaughtered in this senseless violence.

I have had discussions with the leaders of the IFP, and all the discussions that have taken place have been initiated by me over these past five years. I have gone so far as to say that I am prepared to go down on my knees to bring about peace in this country, and to save human lives.

There is a perception which is universal, which we must heed. I may not believe in it, but that perception exists. One has different reactions from different sections of the population about any issue of importance in this country. The perception is that Whites in this country live in comfort, in places which are sufficiently policed, where there is electricity and every movement in the streets can easily be monitored. In contrast to this, it is perceived that the position is different in Black areas, amongst Africans, Coloureds and Indians. As far as Whites are concerned, the loss of 20 000 Black lives means nothing to them. That is the perception. I am talking about perceptions people have. I may not subscribe to that perception as an individual, but that is the perception. What has taken place here? None of the contributors referred to this tragedy where innocent people have been slaughtered in the course of this violence.

I do not consider the Constitution to be more important than human lives. What is important is to protect human beings in this country; to make them safe and secure, and if any party or any individual threatens the lives of human beings, it is my duty as the President of this country and as the head of this Government, to act very decisively and firmly. That is what I am going to do. …

I have briefed the leaders of political parties inside and outside the Government of National Unit, that there is a serious situation in KwaZulu-Natal. Chief Buthelezi has made a public call to Zulus to rise against the central Government. He has said that if they do not get the right to self-determination, it is not worth being alive. Not only has he made this statement, but this threat is now being implemented in that province.

On Sunday, I addressed a rally in the Nqutu district. A bus which was carrying members of the public to the rally was stopped by the IFP, and the IFP asked the people to turn back. When the driver refused, members of the IFP shot and killed a passenger, and the driver had to go back.

On Monday, I went to Emboland on the invitation of the Chief there. Three buses coming from Umbumbulu were stopped by the members of the IFP and told to return. After an hour's argument, the police intervened and ensured that those buses reached the rally. Everyone knows what happened in the Umlazi stadium. According to Gen. Serfontein, about 1 000 members of the IFP tried to storm that rally, and the police had to use teargas twice to drive them back.

In spite of that, members of the IFP were able to shoot and injure six people inside the stadium, including a young boy whom they shot in the eye. They also destroyed about four shacks on the borders of the stadium. That is what is happening as a result of the statement made by Chief Buthelezi.

Members here who have never known about the tradition of human rights and of democracy are now giving gratuitous advice to those people who fought hard to bring about democracy and the culture of human rights in this country. They are talking about the sanctity of the Constitution, and yet, when they were in power, at the slightest excuse they interfered with the Constitution. They even amended the entrenched process which protected the language rights of people in this country, and took away one of the most important rights of people, namely the right of the Coloured people to vote in this country. Now they are lecturing us on the sanctity of the Constitution.

When the Senate debated the President’s Budget a month later, the issue was again raised, this time along with a question about the pre-election shooting of IFP demonstrators outside the ANC headquarters (see Chapter 6- The dynamics of parliament)

. . . whatever the origins of the IFP were, the NP soon took them over and used them in order to undermine democracy in this country, to undermine the United Democratic Front and now the ANC. Members must remember that when the then President Mr De Klerk was asked in July 1991 whether he had given the IFP R8 million plus R250 000, he said that they had, but that he had stopped it.

What is happening in KwaZulu-Natal is part of the agenda of the NP. One can see it, even now, from the way in which they themselves are handling the matter [in the debate]. I am sure they are quite honest about the views that they are expressing, but they are so used to managing the IFP, that it can do no wrong.

They talk about Mandini. Did they know that in that area alone there are more than 2 000 criminal cases which are unsolved? More than 2 000, including several cases of murder! They are speaking here as people who stay in the White areas, where 80 per cent of the security forces of this country are deployed. They are well-protected; their police stations have vehicles; their men can do their rounds in vehicles; and their detectives each handle about four to five cases at a time, using official vehicles.

In the Black areas-the African, Coloured and Indian areas-each detective handles about 60 cases. They have no transport, and have to use public transport to do so. That is why crime has rocketed so much in those areas. It is the fault of the NP government that this is so. However, we are saying this, not so much to blame them, but to put their remarks in their proper context.

They have advised us…on how we should handle the whole question of the strife between the IFP and the ANC. In the first place, it is not accurate to project the problem as a clash between the ANC and the IFP only. The NP is amongst the guilty parties in this whole affair, because they have over decades incited the IFP to do certain things which are not consistent with the law of the country. That is why they find it difficult to break away from the wrongs that the IFP are doing.

I have been holding discussions with the IFP ever since I came out of prison. For every other meeting we held, the initiative was taken by myself. Not once has the IFP taken that initiative, except now when Dr Mzimela did so. However, all the other initiatives were taken by the ANC. We have had discussions as organisations. I have called Chief Buthelezi, and had one-on-one discussions with him. All of them failed to resolve anything, but all the NP can say here is that I should hold discussions with Buthelezi.

Why should I repeat today what I have been doing for the past five years, which has failed to resolve anything? Are they so barren that they have no fresh suggestions to make, except for saying that I should repeat what I have been doing for the past five years? That is what they are saying! If not, they should tell me what I should do. I have used negotiations, persuasion, but there has been no development at all. What should I do now?

... We do not need lectures either about the Constitution or the funding of provinces. The NP amended the constitution when it suited them, left and right with no respect!

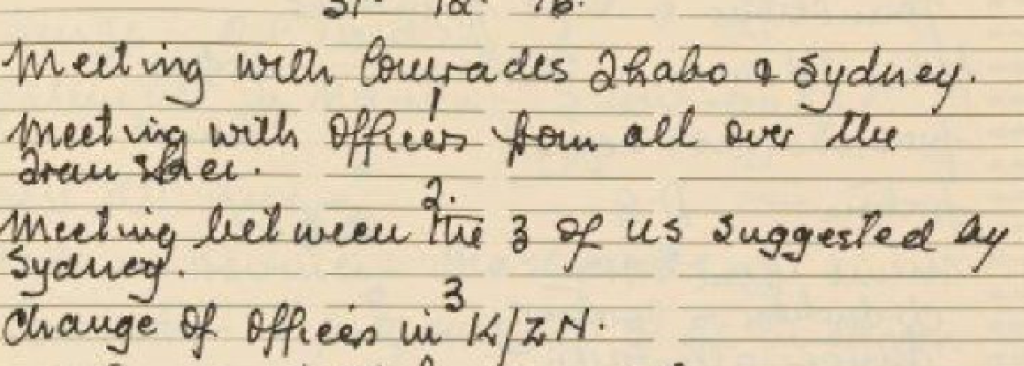

A few days later the Cabinet was briefed on the plans under way to arrest the violence in KwaZulu Natal.376 A working group was established, consisting of the president, the two deputy presidents, and the minister of home affairs, Buthelezi, to liaise with the province and relevant structures on the concrete steps being taken.377

The emphasis now shifted away from combative public dispute to concerted security action to create stability and also give space to a political processes aimed at resolving differences.

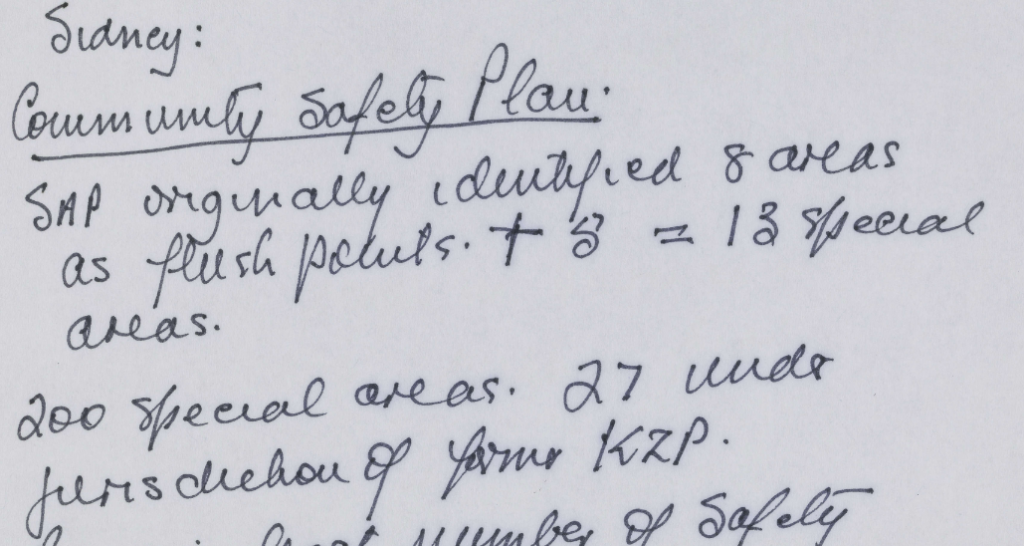

The security measures included the deployment of additional troops and police to the province, accompanied by intelligence officers and detectives; the establishment of community police forums; a Community Safety Plan – covering the whole country - focused on areas identified as flash points; and continuation of the work of the Investigation Task Unit to identify hit-squad structures.378 There were some changes at senior levels of the provincial police and some reorganisation of the National Investigating Unit.379 Permits on rifles granted by the KwaZulu bantustan were withdrawn, and a ban was declared on carrying dangerous weapons in public in 74 magisterial districts, in KwaZulu-Natal and in other areas affected by the violence. The aim was to reduce violence, injury and death involving ‘traditional’ and homemade weapons such as fighting sticks, spears, clubs, pangas and so on. Though decried by Buthelezi and at times defied in IFP protests as a politically motivated measure against people for whom such weapons were merely ‘cultural accoutrements’, most of the deaths in that period had involved weapons other than guns.380

Intelligence played a big part in implementing the security action. The conviction that a ‘hidden hand’ or ‘third force’ was fomenting the violence was based initially on community experience, interpreted in the light of counter-revolution in other countries. Gradually it hardened into knowledge substantiated by cumulative exposure of the hit-squads and their lines of command. The first breakthrough led to the conviction in 1992, despite an attempted cover-up, of police officers responsible for a massacre in the Natal village of Trust Feeds in 1988.

After the election it was anticipated that the Truth and Reconciliation Commission would, by granting amnesty in exchange for disclosure, further expose and thereby neutralise the structures that had been set up to foment violence. But it would be some time before the TRC was established and action had to be taken. Adopting the pre-election approach, when a team of specialist investigators worked with a witness protection programme, a hand-picked Investigation Task Unit was set up under the leadership of the provincial superintendent, Frank Dutton, who had made the Trust Feeds breakthrough. The unit got the cooperation of a significant number of people previously involved in the hit squads who came forward with information, some of whom had already been arrested and who were cooperating from prison, and some of whom subsequently went to the Truth Commission. Consequently, enough became known about the extent to which people at the top of the security establishment of central government or homelands were implicated, even if they did not themselves come forward, so that steps could be taken to close the space for the continuation of violent activities.381

people involved previously in the hit squads were coming forward with information

In time the ITU traced the lines of command and protection of hit-squads, sometimes to high levels. The exposure, through these investigations, of senior political figures created dilemmas. The Attorney-General of the province found himself in September 1995 faced with the prospect, as a result of the ITU’s work, of having to prosecute senior IFP and KwaZulu Police officials, people who had been colleagues in the old order.

When evidence pointing to complicity in violence at high levels in the IFP faced the ANC with the prospect of IFP arrests of that could have serious repercussions that could undermine the political processes to promote peace, the ANC provincial leadership baulked at the prospect, despite their criticism of the pace of stabilisation. Later, in 1997 as violence persisted, the provincial leadership proposed a special amnesty process for the province for actions after the TRC cut-off date, as a measure that could help end the persisting violence. Though this proposal had national support, including that of Mandela, and featured in talks between the ANC and IFP for some time, it was eventually shelved.382

Progress in dealing with violence that had been cultivated over a long period was gradual, given also that there was also obstruction of the investigations and protection of those involved. Against a background of continuing incidents, terrible events and massacres still happened.

Without eradicating the problem of violence, the teeth of structures originating within the apartheid security structures were finally drawn in Richmond in 1999. The leading ANC member in the area, a warlord, was revealed to have been an agent of the apartheid security forces and to be continuing to operate within a structure set up at that time. His exposure, arrest and trial was followed by violent retribution in which several people were killed, including ANC councilors elected after this arrest. He himself was assassinated after the case against him fell apart due to the withdrawal of intimidated witnesses.