Even under the most favourable circumstances, reconciling traditional leadership with democracy would call on political and constitutional creativity combined with political trust. For South Africa on the path to democracy the challenge was magnified by the legacy of abuse and distortion of traditional – indigenous – leadership, first in the immediate aftermath of colonial conquest and then under the system of apartheid – and in due course by regional political parties based on bantustan administrations.

The resulting mistrust, obfuscation and vested interests played into the negotiations for a new constitution, leaving key issues to be gradually and only partially resolved in drawn-out contestation during Mandela’s presidential years. In KwaZulu-Natal, the process was violent to an extent that could have jeopardised the country’s stability.

For Mandela, and the ANC, securing a place for traditional leadership in democratic South Africa – without compromising democratic principle – was both possible and necessary. At its founding the ANC had an upper house of traditional leaders, acknowledging the role of kingdoms and traditional leaders in organising resistance to colonial intrusion. Recognising also the continuing respect for traditional leadership in much of South Africa, it was expected that they would help overcome the division which had led to defeat and in so doing, in the words of Pixley ka Seme, help ‘bury the demon of tribalism’. Later, as traditional leadership became implicated in the administration of segregated structures, the upper house was dropped. But by the late 1980s Contralesa, led by traditional leaders playing a part in resistance, was included in the broad democratic front the ANC was building. The ANC’s 1989 Constitutional Guidelines for a Democratic South Africa, declared that ‘The institution of hereditary rulers and chiefs shall be transformed to serve the interests of the people as a whole in conformity with the democratic principles embodied in the constitution.’336

But because the apartheid regime had used traditional leadership as an instrument of division and coercion in the form of bantustan administrations, ‘transformation’ needed much more than defining constitutional principles which married hereditary leadership of communities and democratic political authority. The institution had to be extricated from the web of the apartheid state. The bantustans would have to be reincorporated into a unitary South African state and traditional leaders freed from the political parties based on those administrations. It also required convincing a strongly skeptical and indeed hostile sentiment in the ANC itself, fed either by rejection of hereditary authority in principle or by historical anger or both.

As resistance mounted traditional leadership, already implicated in colonial and white minority rule as instruments of rural administration, became one of the principal means by which the apartheid regime sought to sustain white-minority control of the country. Mandela observed in his Treason Trial evidence that government talk of autonomy and separate homelands for Africans took shape as mass mobilisation grew with the Defiance Campaign and Programme of Action . In time nine ‘homelands’ were established, each decreed to be the area in which South Africans assigned to ethnic groups defined by the government would exercise political rights and ultimately citizenship as the areas become ‘independent’.

Madiba was working within the ANC policy, the founding policy

The homelands policy set back the unification that the founding ANC had initiated, as compliant traditional leaders acquired vested interests in separation. Lines of succession were manipulated to ensure compliance. Chiefs who didn’t toe the line were dismissed. The constitutions of the homelands, mostly written in Pretoria, created elected assemblies which were dominated by traditional leaders, whether by means of overriding powers of upper houses of traditional leaders; quotas of traditional leaders in legislative assemblies that ensured them a majority, or regional parties that they controlled.337

Political prisoners on Robben Island sharply debated these developments in the 1970s. Mandela’s position was spelt out with strategic urgency in an essay, Clear the Obstacles and Confront the Enemy.338

Time is of the essence and we cannot afford to hesitate. One of the most burning issues in the country today is the independence of the Transkei and other bantustans, and the whole question of our tactics towards apartheid institutions. Separate development is just another name for apartheid and the use of the phrase to describe the same thing must be taken as an admission by the regime that apartheid as a political concept is discredited. The liberation movement totally rejects separate development and has boycotted the elections to the legislative assemblies in the affected areas.

It is not possible to examine the merits and demerits of the highly controversial question of the boycott as a political weapon here. Suffice it to say that the very first elections held in the Transkei in 1963 revealed serious weaknesses on our part. The question whether or not the elections should be boycotted was treated by some as one of principle rather than of tactics, and the actual decision taken bore no relationship whatsoever to the question whether we were in a position to carry out that resolution. Of course, tactics must flow out of principle if opportunism is to be avoided. The test always is whether the pursuit of a particular line will enable us to reach our objectives sooner or whether it will retard the struggle. It would have been correct for us to take part in the elections if this would speed up the defeat of apartheid. As it is, the tactics we used showed we were out of touch with the actual situation. We made no proper assessment of the position, were unable to predict the reaction of the people and not a single organisation was strong enough to launch the boycott campaign. Although the majority of those who voted in the 1963 Transkei elections emphatically rejected separate development, they chose to use the legislative assembly as a platform to fight apartheid. Two other elections have since been held in the Transkei and there was a swing in favour of the Transkei National Independence Party (TNIP) and the independence of the area. In other bantustans the trend was similar.

Some may prefer not to say a word in regard to the mistakes we have made and the weaknesses shown in the course of our political work. The fact that apartheid institutions are in operation in certain areas is a reflection on us, and a measure of our own weaknesses. Of course, it is our duty to condemn and expose those who have gone over to the enemy and who believe that freedom can be attained by working within the framework of apartheid institutions. But merely to vent our frustration on all those who have gone into these institutions irrespective of their motives for doing so and the line they pursue inside these bodies is not only dogmatic and naive, but entails the danger of alienating potential allies. We should concentrate more on constructive self-criticism and on frankly and publicly acknowledging our own mistakes to our own people. Far from being a sign of weakness it is a measure of one's strength and confidence, which will pay dividends in the end.

The movement, however, faces an entirely new development: the independence of the Transkei, which will be followed by other bantustans. The Transkei will have an independent legislature, judiciary and executive and may control its foreign relations. Such independence will be the product of separate development, a policy that we unequivocally reject. It will mean breaking up into small separate states a country we seek to free intact. The crucial question is whether we stick to our tactics and ask people to boycott independence or whether the moment has come for a review of the whole question. People in the affected areas will approach the question in a practical way. The heavy and visible yoke of white oppression will have gone. For the first time since conquest the people will run their own affairs. Now Africans will be able to be judges, magistrates, attorneys-general, inspectors of education, postmasters, army and police officers, and they will occupy other top positions in the civil service. Do we ask them to stick to the status quo ante, the maintenance of white supremacy in their areas, and refuse to accept these positions? If we were unable to carry the people on the boycott question before independence, can we hope to succeed after independence? Would it not be far better to consider independence as an accomplished fact and then call upon the people in these so-called free territories to help in the fight for a democratic South Africa? …

A related problem is the emergence of several political parties in the bantustans and amongst the Coloureds. This immediately raises the question of the relationship of the liberation movement to these new parties. It is easy to dismiss all of them as a collection of traitors with whom we will settle accounts one day. To brand them as sell-outs helps to divert public attention from our own weaknesses and mistakes. By all means, let us attack those who choose to work with the enemy and isolate them. But often in issues of this nature solutions are not so simple. Throughout its history the movement has drawn into its ranks many who once believed that their aspirations could be realised by co-operation with the government, but who were forced by truth and experience to change their views, and who later occupied top positions in our political organisations. We can reason with the pro-apartheid parties in the bantustans and amongst the Coloureds and Indians and at least try to neutralise them. The anti-apartheid parties are amongst the forces inside the country that continue to expose the evils of colour oppression and in their respective areas fill the void that was left when we were driven underground or into exile. There may be plenty to criticise in the policies and tactics of the Democratic Party of the Transkei, the Seoposengwe Party of Bophuthatswana and the Coloured Labour Party. A major criticism against all of them is that they confine themselves only to legal activities, when the limitations of such an approach have become all too plain. But which political organisation anywhere in history has been free from criticism? Can we afford to label anti-apartheid parties such as these as stooges merely because their tactics differ from ours? Would it not be in the interests of the struggle as a whole to work with them and give them encouragement in their efforts to defeat apartheid? Or better still, has the moment not arrived for us to establish our own political organisations in the bantustans through which we can address the people directly and through which we can work with other anti-apartheid groups? But a divided movement in which freedom fighters fight among themselves cannot win over any substantial section of the population. Only a united movement can successfully undertake the task of uniting the country.

The success of the regime in carrying out its separate development manoeuvres highlights the weakness of the liberation movement particularly in the countryside. Throughout its history the movement has been essentially an urban movement with hardly any significant following in the countryside.

The chiefs have played a key role in the acceptance of the regime's Bantu Authorities and bantustan schemes. However, attempts to place all blame for the introduction of Bantu Authorities on them are made hollow by the introduction of the Urban Bantu Councils in the principal cities, where the liberation movement commands more influence. This emphasises the importance of looking at our own weaknesses and problems objectively and from all angles.

... In exploiting our weakness in the rural areas, the regime probably realised that the independence of each bantustan would result in a sharp drop or total disappearance of whatever following we had there. Once people enjoy the right to manage their own affairs they have won the only right for which they could join the liberation movement. We would be very optimistic if, in spite of these developments, we still expected much support from an independent territory unless we devised new methods of neutralising them or drawing them nearer to us through the exploitation of some of their unresolved major grievances, such as the land question and economic independence. But an even more serious danger for us is looming on the horizon. Our movement is the product of the very social conditions against which we fight and is influenced by changes of these conditions. The emergence of no less than eight ethnic states requiring qualified men to fill the new positions that will become available will revive regionalism and clannish attitudes and cast a severe strain on a movement that is recruited from all the ethnic groups, that lives in exile under extremely difficult conditions, where divisions and quarrels can be very frustrating. Already the fact that some men, who were once politically active, have crossed over to the enemy should serve as a warning to us of the centrifugal forces future developments are likely to set in motion. If we do not iron out our differences and close ranks immediately we may find it difficult, if not impossible, to resist the divisive pressures once independence becomes a fact.

By the time Mandela was released, the United Democratic Front (UDF) had laid the foundation for a broad democratic front which included a sizeable number of traditional leaders.339

by the time the other side released Madiba … they realised we had outflanked them

Many had decided to stake their fate in resisting the bantustan system in its totality, or to use it as a platform against its progenitors. In many areas parties which showed a modicum of anti-apartheid sentiment proved quite popular and quite often election rigging and other subterfuges would be needed to install apartheid puppet politicians. Some traditional leaders went into these structures with the naïve belief that they would confer real power and authority in these confined spaces; but were given a rude awakening by the diktat from Pretoria. In time, more and more decided to make common cause with the liberation movement. A few, on account of personal ambition, harboured anti-apartheid sentiments but thought they could in the long-run use the bantustan platform to displace the liberation movement as the legitimate voice of popular resistance.

In December 1989, just two months before Mandela’s release, the Conference for a Democratic Future brought together thousands of representatives from hundreds of organisations including political parties from several bantustans. Walter Sisulu, recently released from prison, spoke to the conference of the need for a broad front: ‘Our response is to remain steadfast in the search for broader unity. Indeed, we cannot be satisfied with even the broadness of this conference. Our aim is a greater one. It is to unite the whole of our society.’340

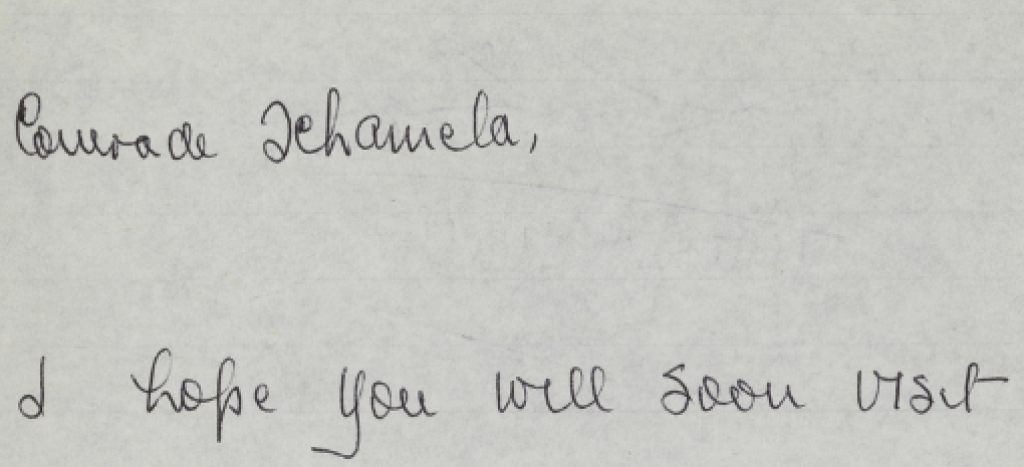

One of Mandela’s priorities after his release and the unbanning of the ANC was the campaign to bring traditional leaders and bantustan parties into the liberation movement camp and deny them to the National Party. He visited the bantustan areas and met with senior traditional leaders. He felt the urgency of action: ‘Comrade Xhamela, I hope you will soon visit homeland leaders’, he says in a note written to Walter Sisulu during a meeting, ‘delay may lead to our being outwitted by Government.’341

When the formal negotiations began, bantustan parties were amongst the participants. To that extent, traditional leaders were directly represented. Days before the first meeting of the Convention for a Democratic South Africa (Codesa I), Mandela issued a statement as President of the ANC calling for the presence of traditional leaders as observers.

The African National Congress, since its foundation on 8 January 1912, has sought to achieve the unity of all the people of South Africa. We enter 1992, and approach our 80th anniversary celebrations, full of optimism for the future.

The Convention for a Democratic South Africa has the real possibility of ushering in a process of fundamental transformation by establishing an interim government of national unity. This would enable elections on the basis of one person one vote, on a system of proportional representation, to take place for a Constituent Assembly, which has the task of drawing up a new, democratic constitution for our country.

But when the question arose of how traditional leaders would take part in the next stage of actual negotiations in CODESA II and beyond, Mandela argued in the ANC’s National Working Committee for a position consistent with his view that while they were an influential social formation they should not have political authority – he argued that they should participate as individual members of provincial delegations, not as an organised formation.

It is clear the majority view is for special status. But there are other options. There is the position taken by Kangwane which is prepared to have only one delegation, including the traditional leaders. This is the most progressive view ... We have discussed the matter with Lebowa, and they would accept one delegation in which various interests are combined, including representation of chiefs. If we can get various political parties to adopt such a position, especially in the homelands, we might be able to come forward with a position which is better than giving them special status. If it is agreed that from an area we have one delegation including traditional leaders this will avoid all complications. ... KwaNdebele would not be opposed. Only Ximoko and Dikwankwetla are doubtful. Transkei would listen to us very carefully, as would Venda. This is an option we should try.

He lost the argument in that meeting, in part because a decision was required within days, leaving too little time to get the agreement of the areas involved. He accepted as a compromise the majority view in favour of special participatory status, in four provincial delegations of traditional leaders.

Later, as the first election approached, he urged activists to be tactical in their approach and not to shun traditional leaders because of their history – as he did when he spoke to young people in April 1994.

I have touched on the question of homeland leaders and traditional chiefs. It is not the policy of the ANC to condemn the chiefs as such. These are our traditional leaders, some of whom have an impressive record in the fight against apartheid. We say we must give them the respect that they deserve as traditional leaders.

You must remember that it is going to be difficult for our organisation to take root and be strong in the countryside unless we are able to work together with them in their respective areas. And those who feel that we have nothing to do with the chiefs do not know the policy of the ANC and have no idea how to strengthen the organisation in the countryside.

In fact, the National Party detected this weakness on our part, of not having strong organisation in the countryside. That is how they succeeded in forcing the homeland policy on the masses of our people....

At the same time, the guiding principle was that democracy would not be compromised, a principle stressed at the ANC’s first National Conference after the election:

We should ... reiterate our recognition of, and respect for, the institution of traditional leaders in all parts of our country. We should also emphasise, as many of these leaders would agree, that restoring this institution to its respected role does not mean that the right of citizens to determine their destiny or for communities to exercise democracy, should be subverted, simply because they happen to live in rural areas.345

And later during the drawing of the final constitution:

I also wish in this regard to advise any traditional leaders in our country to abandon the illusion that they can ever be granted powers which compromise the fundamental objectives of democracy. The present constitution has adequate provisions to address the question of the role of traditional leaders. We accept that these provisions should be carried over into the new constitution. And in this, we know we have the support of the majority of traditional leaders.346

Mandela’s approach to traditional leadership was made clear to those who worked with him during the transition and constitutional negations

From a political point of view he held that the traditional leaders, had many of them a degree of influence in their own areas and so it was important to engage with them. During the negotiations he felt it was important to keep them on side so that they supported the transition and did not oppose it. He also didn’t want the regime to mobilise the traditional leaders against change, and so he engaged with them and kept close to them and met with them. ...

He respected traditional leaders from the point of view that they held respect and following of their communities, those who did, although he was of the view that many of them were illegitimate, he said that over and over. But he didn’t want them to have any role whatsoever in government, they were not elected they were not part of the democracy....

Madiba was comfortable enough about his ethnic background, he wasn’t uncomfortable about that, he didn’t pretend that he didn’t come from the Transkei, or that he didn’t grow up grow up among a traditional community. But he was very clear that he was not going to be painted with that, when people see him, he didn’t want people to see a member of the Tembu royal family, he wanted them to see a South African and it was not by accident: it was very, very deliberate in his mind.347